Behind a locked door in a white-walled basement in a research building in Tempe, Ariz., a monkey sits stone-still in a chair, eyes locked on a computer screen. From his head protrudes a bundle of wires; from his mouth, a plastic tube. As he stares, a picture of a green cursor on the black screen floats toward the corner of a cube. The monkey is moving it with his mind.

The monkey, a rhesus macaque named Oscar, has electrodes implanted in his motor cortex, detecting electrical impulses that indicate mental activity and translating them to the movement of the ball on the screen. The computer isn’t reading his mind, exactly — Oscar’s own brain is doing a lot of the lifting, adapting itself by trial and error to the delicate task of accurately communicating its intentions to the machine. (When Oscar succeeds in controlling the ball as instructed, the tube in his mouth rewards him with a sip of his favorite beverage, Crystal Light.) It’s not technically telekinesis, either, since that would imply that there’s something paranormal about the process. It’s called a “brain-computer interface” (BCI). And it just might represent the future of the relationship between human and machine.

Stephen Helms Tillery’s laboratory at Arizona State University is one of a growing number where researchers are racing to explore the breathtaking potential of BCIs and a related technology, neuroprosthetics. The promise is irresistible: from restoring sight to the blind, to helping the paralyzed walk again, to allowing people suffering from locked-in syndrome to communicate with the outside world. In the past few years, the pace of progress has been accelerating, delivering dazzling headlines seemingly by the week.

At Duke University in 2008, a monkey named Idoya walked on a treadmill, causing a robot in Japan to do the same. Then Miguel Nicolelis stopped the monkey’s treadmill — and the robotic legs kept walking, controlled by Idoya’s brain. At Andrew Schwartz’s lab at the University of Pittsburgh in December 2012, a quadriplegic woman named Jan Scheuermann learned to feed herself chocolate by mentally manipulating a robotic arm. Just last month, Nicolelis’ lab set up what it billed as the first brain-to-brain interface, allowing a rat in North Carolina to make a decision based on sensory data beamed via Internet from the brain of a rat in Brazil.

So far the focus has been on medical applications — restoring standard-issue human functions to people with disabilities. But it’s not hard to imagine the same technologies someday augmenting capacities. If you can make robotic legs walk with your mind, there’s no reason you can’t also make them run faster than any sprinter. If you can control a robotic arm, you can control a robotic crane. If you can play a computer game with your mind, you can, theoretically at least, fly a drone with your mind.

It’s tempting and a bit frightening to imagine that all of this is right around the corner, given how far the field has already come in a short time. Indeed, Nicolelis — the media-savvy scientist behind the “rat telepathy” experiment — is aiming to build a robotic bodysuit that would allow a paralyzed teen to take the first kick of the 2014 World Cup. Yet the same factor that has made the explosion of progress in neuroprosthetics possible could also make future advances harder to come by: the almost unfathomable complexity of the human brain.

From I, Robot to Skynet, we’ve tended to assume that the machines of the future would be guided by artificial intelligence — that our robots would have minds of their own. Over the decades, researchers have made enormous leaps in artificial intelligence (AI), and we may be entering an age of “smart objects” that can learn, adapt to, and even shape our habits and preferences. We have planes that fly themselves, and we’ll soon have cars that do the same. Google has some of the world’s top AI minds working on making our smartphones even smarter, to the point that they can anticipate our needs. But “smart” is not the same as “sentient.” We can train devices to learn specific behaviors, and even out-think humans in certain constrained settings, like a game of Jeopardy. But we’re still nowhere close to building a machine that can pass the Turing test, the benchmark for human-like intelligence. Some experts doubt we ever will.

Philosophy aside, for the time being the smartest machines of all are those that humans can control. The challenge lies in how best to control them. From vacuum tubes to the DOS command line to the Mac to the iPhone, the history of computing has been a progression from lower to higher levels of abstraction. In other words, we’ve been moving from machines that require us to understand and directly manipulate their inner workings to machines that understand how we work and respond readily to our commands. The next step after smartphones may be voice-controlled smart glasses, which can intuit our intentions all the more readily because they see what we see and hear what we hear.

The logical endpoint of this progression would be computers that read our minds, computers we can control without any physical action on our part at all. That sounds impossible. After all, if the human brain is so hard to compute, how can a computer understand what’s going on inside it?

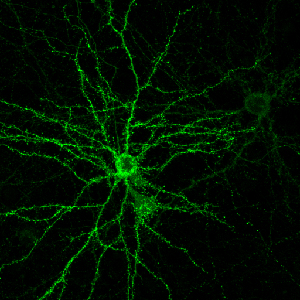

It can’t. But as it turns out, it doesn’t have to — not fully, anyway. What makes brain-computer interfaces possible is an amazing property of the brain called neuroplasticity: the ability of neurons to form new connections in response to fresh stimuli. Our brains are constantly rewiring themselves to allow us to adapt to our environment. So when researchers implant electrodes in a part of the brain that they expect to be active in moving, say, the right arm, it’s not essential that they know in advance exactly which neurons will fire at what rate. When the subject attempts to move the robotic arm and sees that it isn’t quite working as expected, the person — or rat or monkey — will try different configurations of brain activity. Eventually, with time and feedback and training, the brain will hit on a solution that makes use of the electrodes to move the arm.

That’s the principle behind such rapid progress in brain-computer interface and neuroprosthetics. Researchers began looking into the possibility of reading signals directly from the brain in the 1970s, and testing on rats began in the early 1990s. The first big breakthrough for humans came in Georgia in 1997, when a scientist named Philip Kennedy used brain implants to allow a “locked in” stroke victim named Johnny Ray to spell out words by moving a cursor with his thoughts. (It took him six exhausting months of training to master the process.) In 2008, when Nicolelis got his monkey at Duke to make robotic legs run a treadmill in Japan, it might have seemed like mind-controlled exoskeletons for humans were just another step or two away. If he succeeds in his plan to have a paralyzed youngster kick a soccer ball at next year’s World Cup, some will pronounce the cyborg revolution in full swing.

Schwartz, the Pittsburgh researcher who helped Jan Scheuermann feed herself chocolate in December, is optimistic that neuroprosthetics will eventually allow paralyzed people to regain some mobility. But he says that full control over an exoskeleton would require a more sophisticated way to extract nuanced information from the brain. Getting a pair of robotic legs to walk is one thing. Getting robotic limbs to do everything human limbs can do may be exponentially more complicated. “The challenge of maintaining balance and staying upright on two feet is a difficult problem, but it can be handled by robotics without a brain. But if you need to move gracefully and with skill, turn and step over obstacles, decide if it’s slippery outside — that does require a brain. If you see someone go up and kick a soccer ball, the essential thing to ask is, ‘OK, what would happen if I moved the soccer ball two inches to the right?'” The idea that simple electrodes could detect things as complex as memory or cognition, which involve the firing of billions of neurons in patterns that scientists can’t yet comprehend, is far-fetched, Schwartz adds.

That’s not the only reason that companies like Apple and Google aren’t yet working on devices that read our minds (as far as we know). Another one is that the devices aren’t portable. And then there’s the little fact that they require brain surgery.

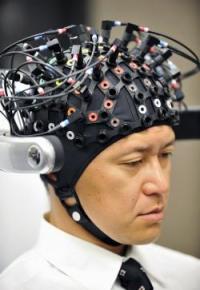

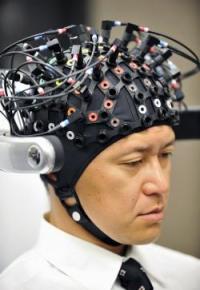

A different class of brain-scanning technology is being touted on the consumer market and in the media as a way for computers to read people’s minds without drilling into their skulls. It’s called electroencephalography, or EEG, and it involves headsets that press electrodes against the scalp. In an impressive 2010 TED Talk, Tan Le of the consumer EEG-headset company Emotiv Lifescience showed how someone can use her company’s EPOC headset to move objects on a computer screen.

Skeptics point out that these devices can detect only the crudest electrical signals from the brain itself, which is well-insulated by the skull and scalp. In many cases, consumer devices that claim to read people’s thoughts are in fact relying largely on physical signals like skin conductivity and tension of the scalp or eyebrow muscles.

Robert Oschler, a robotics enthusiast who develops apps for EEG headsets, believes the more sophisticated consumer headsets like the Emotiv EPOC may be the real deal in terms of filtering out the noise to detect brain waves. Still, he says, there are limits to what even the most advanced, medical-grade EEG devices can divine about our cognition. He’s fond of an analogy that he attributes to Gerwin Schalk, a pioneer in the field of invasive brain implants. The best EEG devices, he says, are “like going to a stadium with a bunch of microphones: You can’t hear what any individual is saying, but maybe you can tell if they’re doing the wave.” With some of the more basic consumer headsets, at this point, “it’s like being in a party in the parking lot outside the same game.”

It’s fairly safe to say that EEG headsets won’t be turning us into cyborgs anytime soon. But it would be a mistake to assume that we can predict today how brain-computer interface technology will evolve. Just last month, a team at Brown University unveiled a prototype of a low-power, wireless neural implant that can transmit signals to a computer over broadband. That could be a major step forward in someday making BCIs practical for everyday use. Meanwhile, researchers at Cornell last week revealed that they were able to use fMRI, a measure of brain activity, to detect which of four people a research subject was thinking about at a given time. Machines today can read our minds in only the most rudimentary ways. But such advances hint that they may be able to detect and respond to more abstract types of mental activity in the always-changing future.

http://www.ydr.com/living/ci_22800493/researchers-explore-connecting-brain-machines