By DENISE GELLENE

Frederick Sanger, a British biochemist whose discoveries about the chemistry of life led to the decoding of the human genome and to the development of new drugs like human growth hormone and earned him two Nobel Prizes, a distinction held by only three other scientists, died on Tuesday in Cambridge, England. He was 95.

His death was confirmed by Adrian Penrose, communications manager at the Medical Research Council in Cambridge. Dr. Sanger, who died at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, had lived in a nearby village called Swaffham Bulbeck.

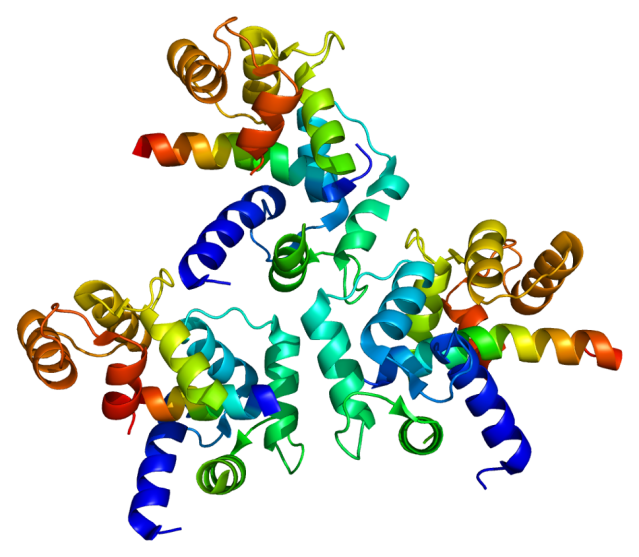

Dr. Sanger won his first Nobel Prize, in chemistry, in 1958 for showing how amino acids link together to form insulin, a discovery that gave scientists the tools to analyze any protein in the body.

In 1980 he received his second Nobel, also in chemistry, for inventing a method of “reading” the molecular letters that make up the genetic code. This discovery was crucial to the development of biotechnology drugs and provided the basic tool kit for decoding the entire human genome two decades later.

Dr. Sanger spent his entire career working in a laboratory, which is unusual for someone of his stature. Long after receiving his first Nobel, he continued to perform many experiments himself instead of assigning them to a junior researcher, as is typical in modern science labs. But Dr. Sanger said he was not particularly adept at coming up with experiments for others to do, and had little aptitude for administration or teaching.

“I was in a position to do more or less what I liked, and that was doing research,” he said.

Frederick Sanger was born on Aug. 3, 1918, in Rendcomb, England, where his father was a physician. He expected to follow his father into medicine, but after studying biochemistry at Cambridge University, he decided to become a scientist. His father, he said in a 1988 interview, “led a scrappy sort of life” in which he was “always going from one patient to another.”

“I felt I would be much more interested in and much better at something where I could really work on a problem,” he said.

He received his bachelor’s degree in 1939. Raised as a Quaker, he was a conscientious objector during World War II and remained at Cambridge to work on his doctorate, which he received in 1943.

However, later in life, lacking hard evidence to support his religious beliefs, he became an agnostic.

“In science, you have to be so careful about truth,” he said. “You are studying truth and have to prove everything. I found that it was difficult to believe all the things associated with religion.”

Dr. Sanger stayed on at Cambridge and soon became immersed in the study of proteins. When he started his work, scientists knew that proteins were chains of amino acids, fitted together like a child’s colorful snap-bead toy. But there are 22 different amino acids, and scientists had no way of determining the sequence of these amino acid “beads” along the chains.

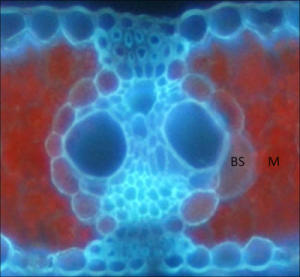

In 1962, Dr. Sanger moved to the British Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, where he was surrounded by scientists studying deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, the master chemical of heredity.

Scientists knew that DNA, like proteins, had a chainlike structure. The challenge was to determine the order of adenine, thymine, guanine and cytosine — the chemical bases from which DNA is made. These bases, which are represented by the letters A, T, G and C, spell out the genetic code for all living things.

Dr. Sanger decided to study insulin, a protein that was readily available in a purified form since it is used to treat diabetes. His choice of insulin turned out to be a lucky one — with 51 amino acids, insulin has a relatively simple structure. Nonetheless, it took him 10 years to unlock its chemical sequence.

His approach, which he called the “jigsaw puzzle method,” involved breaking insulin into manageable chunks for analysis and then using his knowledge of chemical bonds to fit the pieces back together. Using this technique, scientists went on to determine the sequences of other proteins. Dr. Sanger received the Nobel just four years after he published his results in 1954.

Dr. Sanger quickly discovered that his jigsaw method was too cumbersome for large pieces of DNA, which contain many thousands of letters. “For a while I didn’t see any hope of doing it, though I knew it was an important problem,” he said.

But he persisted, developing a more efficient approach that allowed stretches of 500 to 800 letters to be read at a time. His technique, known as the Sanger method, increased by a thousand times the rate at which scientists could sequence DNA.

In 1977, Dr. Sanger decoded the complete genome of a virus that had more than 5,000 letters. It was the first time the DNA of an entire organism had been sequenced. He went on to decode the 16,000 letters of mitochondria, the energy factories in cells.

Because the Sanger method lends itself to computer automation, it has allowed scientists to unravel ever more complicated genomes — including, in 2003, the three billion letters of the human genetic code, giving scientists greater ability to distinguish between normal and abnormal genes.

In addition, Dr. Sanger’s discoveries were critical to the development of biotechnology drugs, like human growth hormone and clotting factors for hemophilia, which are produced by tiny, genetically modified organisms.

Dr. Sanger shared the 1980 chemistry Nobel with two other scientists: Paul Berg, who determined how to transfer genetic material from one organism to another, and Walter Gilbert, who, independently of Dr. Sanger, also developed a technique to sequence DNA. Because of its relative simplicity, the Sanger method became the dominant approach.

Other scientists who have received two Nobels are John Bardeen for physics (1956 and 1972), Marie Curie for physics (1903) and chemistry (1911), and Linus Pauling for chemistry (1954) and peace (1962).

Dr. Sanger received the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award, often a forerunner to the Nobel, in 1979 for his work on DNA. He retired from the British Medical Research Council in 1983.

Survivors include two sons, Robin and Peter, and a daughter, Sally.

In a 2001 interview, Dr. Sanger spoke about the challenge of winning two Nobel Prizes.

“It’s much more difficult to get the first prize than to get the second one,” he said, “because if you’ve already got a prize, then you can get facilities for work and you can get collaborators, and everything is much easier.”