Sol Snyder, Distinguished Service Professor of Neuroscience, Pharmacology and Psychiatry, School of Medicine

Growing up, I never had any strong interest in science. I did well in lots of things in high school. I liked reading philosophy and things like that, but being a philosopher is not a fit job for a nice Jewish boy.

This was in the mid-1950s, and many of my friends were going into engineering, preparatory to joining the then prominent military industrial complex. Others were going to be doctors, so I got the idea that maybe I’d be a psychiatrist. I didn’t have any special affinity for medicine or desire to cast out the lepers or heal mankind.

I was always reading things. My father valued education. He wasn’t a big advice giver, but he … had a lot of integrity. What was important to him was doing the right thing. And he had great respect for the intellectual life and science.

My father’s professional life commenced in 1935 as the 10th employee of what became the NSA. He led a team that broke one of the principal Japanese codes. At the end of World War II, computers were invented, and, if you think about it, what could be the best entity to take advantage of computers than NSA, with its mission of sorting gibberish and looking for patterns. So my father was assigned to look at these new machines and see if they would be helpful. He led the computer installations at NSA.

Summers in college I worked in the NSA. My father taught me to program computers in machine language. Computers were a big influence on me.

I learned at the NSA about keeping secrets. What is top secret, what is need-to-know—that is one of the things you learn in the business. You don’t talk to the guy at the next desk even if you’re working on the same project. If that person doesn’t need to know, you just shut up.

In medical school, I started working at the NIH in Bethesda during the summers and elective periods, largely because the only thing I really did well up to that time was play the classical guitar and one of my guitar students was an NIH researcher. In high school I thought I might go the conservatory route, but that’s even less fitting for a nice Jewish boy than being a philosopher.

It was through my contacts at NIH that I was able to get a position working with future Nobel Prize winner Julius Axelrod. Julie was a wonderful mentor who did research on drugs and neurotransmitters. Working with him was inspirational. I just adored it.

What was notable about Julie was his great creativity, always coming up with original ideas. Even though he was an eminent scientist, he didn’t have a regular office. He just had a desk in a lab. He did experiments with his own two hands every day.

Philosophically, Julie emphasized you go where the data takes you. Don’t worry that you’re an expert in enzyme X and so should focus on that. If the data point to enzyme Y, go for it. Do what’s exciting.

My very first project with Julie was studying the disposition of histamine. I thought I had found that histamine had been converted into a novel product that looked really interesting, and I was wrong. I missed the true product because we separated the chemicals on paper and discarded the radioactivity at the bottom, throwing away the real McCoy. Another lab at Yale found it, led, remarkably, by a close friend since kindergarten. My humiliation didn’t last very long. I learned not to be so sloppy, to take greater care, and, most important, to explore peculiar results.

How does one pick research directions? You can go where it’s “hot,” but there you’re competing with 300 other people, and everyone can make only incremental changes. But if you follow Julie Axelrod’s rules and you don’t worry about what’s hot, or what other people are doing—just go where your data are taking you—then you have a better chance of finding something that nobody else had found before.

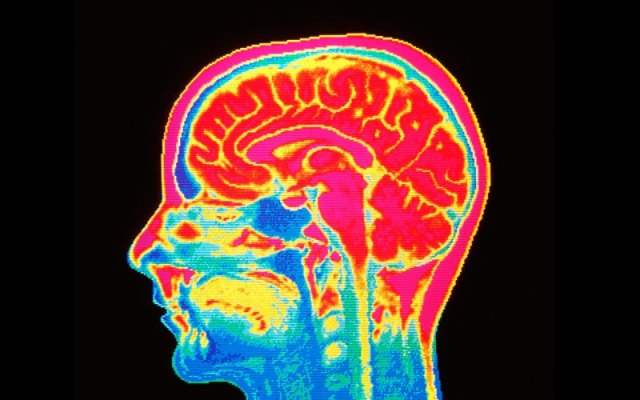

With the discovery of the opiate receptor, I was fortunate to launch a new field: molecular identification of neurotransmitter receptors. Later we discovered that the gas nitrous oxide is a neurotransmitter.

I’m a klutz. I can’t hammer a nail. So for the technical side, like dissecting brains to look at different regions, I enlisted friends. I learned to collaborate, a key element in so many discoveries.

Johns Hopkins has always been a collegial place. People are just friendly and interact with each other. This tradition goes back to the founding of the medical school, permeating the school’s governance as well as research. We tend to be more productive than faculty at other schools, where one gets ahead by sticking an ice pick in the backs of colleagues.

One of my heroes was my guitar teacher, Sophocles Papas, Andrés Segovia’s best friend. Sophocles was an important influence in my life, and we stayed close until he died in his 90s. In a couple of years after commencing lessons, I was giving recitals, all thanks to him. Like Julie, Sophocles emphasized innovative short cuts to creativity.

I’ve remained involved with music. I’m the longest-serving trustee on the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, chairing for many years its music committee. Trustees of arts organizations are typically businesspeople selected for their fundraising acumen. But the person who nominated me reportedly commented, I’d like to propose something radical: I’d like to propose a trustee who cares about music.

Most notable about psychiatry is that the major drugs—antipsychotics for schizophrenia, antidepressants, and anti-anxiety drugs—were all discovered in the mid-1950s. Subsequent tweaking has enhanced potency and diminished side effects, but there have been no major breakthroughs. No new class of drugs since 1958—rather frustrating.

As biomedical science advances, especially with the dawn of molecular biology, our power to innovate is just dazzling. Today’s students take all of this for granted, but those of us who have been doing research for several decades are daily amazed by our abilities to probe the mysteries of life.

The logic of nature is elegant and straightforward. The more we learn about how the body works, the more we are amazed by its beauty and inherent simplicity.

One of my pet peeves is that the very power of modern science leads journal and grant reviewers to expect every “i” dotted and every “t” crossed. Because of this, four years or more of work go into each scientific manuscript. Then, editors and reviewers of journals are so picayune that revising a paper consumes another year.

Now let’s consider the poor postdoctoral fellow or graduate student. To move forward in his or her career requires at least one major publication—a five-year enterprise. If you only have one shot on goal, one paper in five years, your chances of success shrivel. The duration of PhD training and postdoctoral training is getting so long that from the entry point at graduate school to the time you’re out looking for a job as an assistant professor is easily 12, 15 years. Well, that is ridiculous. If you got paid $10 million at the end of this road, that would be one thing, but scientists earn less than most other professionals. We’re deterring the young smart people from going into science.

Biomedical researchers don’t work in a vacuum. They work with grad students and postdoctoral fellows, so being a good mentor is key to being a good scientist. Keep your students well motivated and happy. Have them feel that they are good human beings, and they will do better science.

The most important thing is that you value the integrity of each person. I ask my students all the time, What do you think? And this discussion turns into minor league psychotherapy. Ah, you think that? Tell me more. Tell me more.

The “stupidest” of the students here are smarter than me. It’s a pleasure to watch them emerge.

I see my life as taking care of other people. Although I didn’t go to medical school with any intelligent motivation, once I did, I loved being a doctor and trying to help people. And I love being a psychiatrist and trying to understand people, and I try to carry that into everything I do.

In medical research, all of us want to find the causes and cures for diseases. I haven’t found the cause of any disease, although with Huntington’s disease, we are making inroads. And, of course, being a pharmacologist, my métier is discovering drugs and better treatments.

My secret? I come to work every day, and I keep my own calendar. That way I have free time to just wander around the lab and talk to the boys and girls and ask them how it’s going. That’s what makes me happy.

Sol Snyder joined Johns Hopkins in 1965 as an assistant resident in Psychiatry and would later become the youngest full professor in JHU history. In 1978, he received the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award for his role in discovering the brain’s opiate receptors. In 1980, he founded the School of Medicine’s Department of Neuroscience, which in 2006 was renamed the Solomon H. Snyder Department of Neuroscience.

http://hub.jhu.edu/gazette/2014/january-february/what-ive-learned-sol-snyder

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solomon_H._Snyder