Penises grown in laboratories could soon be tested on men by scientists developing technology to help people with congenital abnormalities, or who have undergone surgery for aggressive cancer or suffered traumatic injury.

Researchers at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, are assessing engineered penises for safety, function and durability. They hope to receive approval from the US Food and Drug Administration and to move to human testing within five years.

Professor Anthony Atala, director of the institute, oversaw the team’s successful engineering of penises for rabbits in 2008. “The rabbit studies were very encouraging,” he said, “but to get approval for humans we need all the safety and quality assurance data, we need to show that the materials aren’t toxic, and we have to spell out the manufacturing process, step by step.”

The penises would be grown using a patient’s own cells to avoid the high risk of immunological rejection after organ transplantation from another individual. Cells taken from the remainder of the patient’s penis would be grown in culture for four to six weeks.

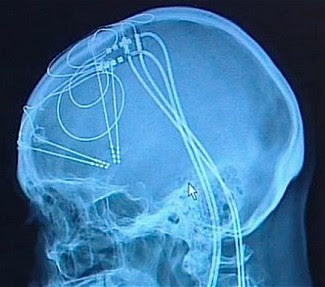

For the structure, they wash a donor penis in a mild detergent to remove all donor cells. After two weeks a collagen scaffold of the penis is left, on to which they seed the patient’s cultured cells – smooth muscle cells first, then endothelial cells, which line the blood vessels. Because the method uses a patient’s own penis-specific cells, the technology will not be suitable for female-to-male sex reassignment surgery.

“Our target is to get the organs into patients with injuries or congenital abnormalities,” said Atala, whose work is funded by the US Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine, which hopes to use the technology to help soldiers who sustain battlefield injuries.

As a paediatric urological surgeon, Atala began his work in 1992 to help children born with genital abnormalities. Because of a lack of available tissue for reconstructive surgery, baby boys with ambiguous genitalia are often given a sex-change at birth, leading to much psychological anguish in later life. “Imagine being genetically male but living as a woman,” he said. “It’s a firmly devastating problem that we hope to help with.”

Asif Muneer, a consultant urological surgeon and andrologist at University College hospital, London, said the technology, if successful, would offer a huge advance over current treatment strategies for men with penile cancer and traumatic injuries. At present, men can have a penis reconstructed using a flap from their forearm or thigh, with a penile prosthetic implanted to simulate an erection.

“My concern is that they might struggle to recreate a natural erection,” he said. “Erectile function is a coordinated neurophysiological process starting in the brain, so I wonder if they can reproduce that function or whether this is just an aesthetic improvement. That will be their challenge.”

Atala’s team are working on 30 different types of tissues and organs, including the kidney and heart. They bioengineered and transplanted the first human bladder in 1999, the first urethra in 2004 and the first vagina in 2005.

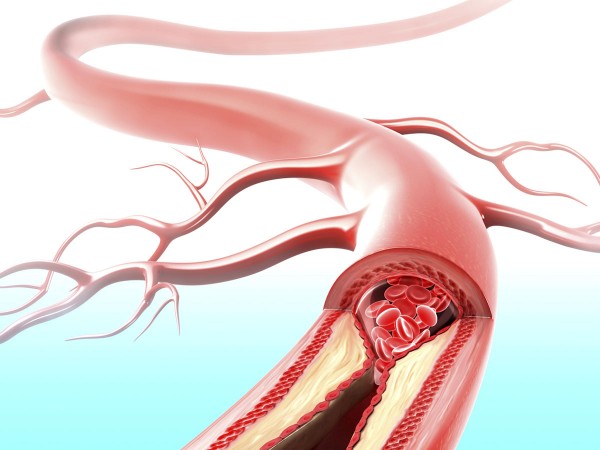

Professor James Yoo, a collaborator of Atala’s at Wake Forest Institute, is working on bioengineering and replacing parts of the penis to help treat erectile dysfunction. His focus is on the spongy erectile tissue that fills with blood during an erection, causing the penis to lengthen and stiffen. Disorders such as high blood pressure and diabetes can damage this tissue, and the resulting scar tissue is less elastic, meaning the penis cannot fill fully with blood.

“If we can engineer and replace this tissue, these men can have erections again,” said Yoo, acknowledging the many difficulties. “As a scientist and clinician, it’s this possibility of pushing forward current treatment practice that really keeps you awake at night.”

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/oct/05/laboratory-penises-test-on-men