Scientists have turned light signals from distant stars into sound. By analysing the amount of hiss in the sound, they can work out the star’s surface gravity and what stage it’s at in its evolution from dwarf to red giant.

Category: Science

University of Iowa researchers uncover mechanism of infective endocarditis

University of Iowa researchers have discovered what causes the lethal effects of staphylococcal infective endocarditis – a serious bacterial infection of heart valves that kills approximately 20,000 Americans each year. According to the UI study, the culprits are superantigens — toxins produced in large quantities by Staphylococcus aureus bacteria — which disrupt the immune system, turning it from friend to foe.

“The function of a superantigen is to ‘mess’ with the immune system,” says Patrick Schlievert, PhD, UI professor and chair of microbiology at the UI Carver College of Medicine. “Our study shows that in endocarditis, a superantigen is over-activating the immune system, and the excessive immune response is actually contributing very significantly to the destructive aspects of the disease, including capillary leakage, low blood pressure, shock, fever, destruction of the heart valves, and strokes that may occur in half of patients.”

Other superantigens include toxic shock syndrome toxin-1, which Schlievert identified in 1981 as the cause of toxic shock syndrome.

Staph bacteria is the most significant cause of serious infectious diseases in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and infective endocarditis is the most serious complication of staph bloodstream infection. This dangerous condition affects approximately 40,000 people annually and has a death rate of about 50 percent. Among patients who survive the infection, approximately half will have a stroke due to the damage from the aggressive infection of the heart valves.

Despite the serious nature of this disease, little progress has been made over the past several decades in treating the deadly condition.

The new study, led Schlievert, and published Aug. 20 in the online open-access journal mBio, suggests that blocking the action of superantigens might provide a new approach for treating infective endocarditis.

“We have high affinity molecules that neutralize superantigens and we have previously shown in experimental animals that we can actually prevent strokes associated with endocarditis in animal models. Likewise, we have shown that we can vaccinate against the superantigens and prevent serious disease in animals,” Schlievert says.

“The idea is that either therapeutics or vaccination might be a strategy to block the harmful effects of the superantigens, which gives us the chance to do something about the most serious complications of staph infections.”

The UI scientists used a strain of methicillin resistant staph aureus (MRSA), which is a common cause of endocarditis in humans, in the study. They also tested versions of the bacteria that are unable to produce superantigens. By comparing the outcomes in the animal model of infection with these various bacteria, the team proved that the lethal effects of endocarditis and sepsis are caused by the large quantities of the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin C (SEC) produced by the staph bacteria.

The study found that SEC contributes to disease both through disruption of the immune system, causing excessive immune response to the infection and low blood pressure, and direct toxicity to the cells lining the heart.

Low blood flow at the infection site appears to be one of the consequences of the superantigen’s action. Increasing blood pressure by replacing fluids reduced the formation of so-called vegetations – plaque-like meshwork made up of cellular factors from the body and bacterial cells — on the heart valves and significantly protected the infected animals from endocarditis. The researchers speculate that increased blood flow may act to wash away the superantigen molecules or to prevent the bacteria from settling and accumulating on the heart valves.

In addition to Schlievert, the research team included Wilmara Salgado-Pabon, PhD, the first author on the study, Laura Breshears, Adam Spaulding, Joseph Merriman, Christopher Stach, Alexander Horswill, and Marnie Peterson.

The research was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI74283, AI57153, AI83211, and AI73366).

http://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/news/2013/08/bacterial-toxins-cause-deadly-heart-disease.aspx

New research shows that male humpback whales sing in unison to attract females

The mournful, curiously repetitious yet ever-changing songs of male humpback whales have long puzzled scientists. The tunes are part of the males’ mating displays, but researchers don’t know their exact function, or which males in a population are doing the singing. Now, scientists who’ve been studying the giant marine mammals in Hawaii for almost 40 years report that even sexually immature males join older males in singing, apparently as a way to learn the music and to amplify the song. The beefed-up, all-male choruses may attract more females to the areas where the songsters hang out.

Scientists generally thought that only adult male humpbacks (Megaptera novaeangliae) sing, says Louis Herman, a marine mammal biologist emeritus at the University of Hawaii, Manoa, and the lead author of the new study. “But that’s just because you can’t easily tell which ones are mature and which ones are immature,” he says. “We know that mature males are larger than immature ones, so we had to figure out an unobtrusive way to measure them in the open ocean.”

Herman and his team hit on a technique by looking at 20th century whaling records. Biologists with whaling operations in the Southern Ocean had the opportunity to measure many humpbacks killed during the commercial hunts. They determined, based on the weight of males’ testes, that the whales reached sexual maturity at a body length of 11.2 meters. Working independently, whaling biologists in Japan, who also measured killed whales, reached a similar conclusion; they described 11.3 meters as the break point between adolescents and adults.

To determine the lengths of living male humpbacks, Herman’s group analyzed digital videos that they made between 1998 and 2008 of 87 of the whale singers. The males were recorded as they sang in the waters off the Hawaiian islands of Maui, Lanai, Molokai, and Kahoolawe during their winter mating season. A swimmer carried the camera in one hand and in the other hand carried a sonar device, which measured the distance from the camera to the whale. The swimmer began filming when the whale assumed a horizontal position (singing whales are typically canted with their heads downward), so that he or she could capture the full body length of the whale while keeping the camera’s axis perpendicular to the whale and close to its midline. The researchers calculated the whales’ body lengths from these images and the distance measurements.

The scientists found that the whales varied in length from 10.7 meters to 13.6 meters. Using 11.3 meters as the boundary for sexually mature adults, the researchers counted 74 humpback singers as mature and 13 as immature. The team has been following individual humpbacks (which are identified by the unique markings on their tail flukes) for decades, and its analysis also showed that some individual males have been singing for 17 to 20 years. “It is a lifelong occupation for them,” says Herman, who notes that male calves and probably 1-year-old males don’t join in.

During the winter months in Hawaii, the male humpbacks assemble in areas that the researchers call arenas, where the males sing and compete for females. Typically, the singers are widely dispersed around their arenas, which may help amp up the reach of the chorus. Males also sing in other social situations, such as while escorting a female humpback and her calf.

When chorusing at the arenas, immature and mature whales are engaged in an unintentional mutual benefits game, Herman and his colleagues argue. By singing with the big boys, the youngsters indirectly learn the songs and the social rules of the mating grounds. The older males, in turn, gain an extra voice in their asynchronous chorus, his team reports in an upcoming issue of Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. “We know that the females don’t respond to an individual male’s song,” Herman says. “It’s not like a songbird’s song, designed to attract a female and repel other males. The humpbacks’ songs are meant to attract females to the arena.” That is, they tell the gals where the boys are. And another voice, even one of a young, inexperienced male, may help carry the message, he says.

The findings strengthen the still controversial idea that gatherings of male humpback whales may be similar to some birds’ lek mating systems, such as those of the sage grouse, which also feature male assemblages. If proved, humpbacks would be the first whale known to have this type of system.

“This is great stuff,” says Phillip Clapham, a cetacean biologist at the National Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle, Washington. He applauds the idea of the males’ chorus serving to “collectively ‘call in’ the females.” He adds that “we’ve known for many years that only male humpbacks sing, but no one had ever managed to figure out a way to determine the maturational class of the singers, so this is a significant advance.”

Now all Herman and his team have to do is determine which of the male singers in the chorus a female actually mates with—an event the researchers have yet to see.

http://news.sciencemag.org/plants-animals/2013/08/mens-chorus%E2%80%94-whales

Thanks to Dr. Rajadhyaksha for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.

After cardiac arrest, a final surge of brain activity could contain vivid experience, new research in rodents suggests.

What people experience as death creeps in—after the heart stops and the brain becomes starved of oxygen—seems to lie beyond the reach of science. But the authors of a new study on dying rats make a bold claim: After cardiac arrest, the rodents’ brains enter a state similar to heightened consciousness in humans. The researchers suggest that if the same is true for people, such brain activity could be the source of the visions and other sensations that make up so-called near-death experiences.

Estimated to occur in about 20% of patients who survive cardiac arrest, near-death experiences are frequently described as hypervivid or “realer-than-real,” and often include leaving the body and observing oneself from outside, or seeing a bright light. The similarities between these reports are hard to ignore, but the conversation about near-death experiences often bleeds into metaphysics: Are these visions produced solely by the brain, or are they a glimpse at an afterlife outside the body?

Neurologist Jimo Borjigin of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, got interested in near-death experiences during a different project—measuring the hormone levels in the brains of rodents after a stroke. Some of the animals in her lab died unexpectedly, and her measurements captured a surge in neurochemicals at the moment of their death. Previous research in rodents and humans has shown that electrical activity surges in the brain right after the heart stops, then goes flat after a few seconds. Without any evidence that this final blip contains meaningful brain activity, Borjigin says “it’s perhaps natural for people to assume that [near-death] experiences came from elsewhere, from more supernatural sources.” But after seeing those neurochemical surges in her animals, she wondered about those last few seconds, hypothesizing that even experiences seeming to stretch for days in a person’s memory could originate from a brief “knee-jerk reaction” of the dying brain.

To observe brains on the brink of death, Borjigin and her colleagues implanted electrodes into the brains of nine rats to measure electrical activity at six different locations. The team anesthetized the rats for about an hour, for ethical reasons, and then injected potassium chloride into each unconscious animal’s heart to cause cardiac arrest. In the approximately 30 seconds between a rat’s last heartbeat and the point when its brain stopped producing signals, the team carefully recorded its neuronal oscillations, or the frequency with which brain cells were firing their electrical signals.

The data produced by electroencephalograms (EEGs) of the nine rats revealed a highly organized brain response in the seconds after cardiac arrest, Borjigin and colleagues report online today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. While overall electrical activity in the brain sharply declined after the last heartbeat, oscillations in the low gamma frequency (between 25 and 55 Hz) increased in power. Previous human research has linked gamma waves to waking consciousness, meditative states, and REM sleep. These oscillations in the dying rats were synchronized across different parts of the brain, even more so than in the rat’s normal waking state. The team also noticed that firing patterns in the front of the brain would be echoed in the back and sides. This so-called top-down signaling, which is associated with conscious perception and information processing, increased eightfold compared with the waking state, the team reports. When you put these features together, Borjigin says, they suggest that the dying brain is hyperactive in its final seconds, producing meaningful, conscious activity.

The team proposed that such research offers a “scientific framework” for approaching the highly lucid experiences that some people report after their brushes with death. But relating signs of consciousness in rat brains to human near-death experiences is controversial. “It opens more questions than it answers,” says Christof Koch, a neuroscientist at the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, Washington, of the research. Evidence of a highly organized and connected brain state during the animal’s death throes is surprising and fascinating, he says. But Koch, who worked with Francis Crick in the early 1980s to hypothesize that gamma waves are a hallmark of consciousness, says the increase in their frequency doesn’t necessarily mean that the rats were in a hyperconscious state. Not only is it impossible to project any mental experience onto these animals, but their response was also “still overlaid by the anesthesiology,” he says; this sedation likely influenced their brain response in unpredictable ways.

Others share Koch’s concerns. “There is no animal model of a near-death experience,” says critical care physician Sam Parnia of Stony Brook University School of Medicine in New York. We can never confirm what animals think or feel in their final moments, making it all but impossible to use them to study our own near-death experiences, he believes. Nonetheless, Parnia sees value in this new study from a clinical perspective, as a step toward understanding how the brain behaves right before death. He says that doctors might use a similar approach to learn how to improve blood flow or prolong electrical activity in the brain, preventing damage while resuscitating a patient.

Borjigin argues that the rat data are compelling enough to drive further study of near-death experiences in humans. She suggests monitoring EEG activity in people undergoing brain surgery that involves cooling the brain and reducing its blood supply. This procedure has prompted near-death experiences in the past, she says, and could offer a systematic way to explore the phenomenon.

read more here: http://news.sciencemag.org/brain-behavior/2013/08/probing-brain%E2%80%99s-final-moments

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.

Diamond Light Source particle accelerator enables discovery of CRF1 receptor structure that may help design new drugs for anxiety and depression

Scientists have used one of the world’s most powerful X-ray machines to identify the molecule responsible for feelings of stress, anxiety and even depression.

The pituitary gland is known to the medical world as a key player in stress and anxiety, as it releases stress chemicals in the blood.

However, scientists have now discovered that the protein receptor CRF1 is responsible for releasing hormones which can cause anxiety and depression over extended periods of time. The protein receptor is found in the brain and controls our response to stress. When it detects stress molecules released by the hypothalamus, it releases these hormones.

The study, conducted by drug company Heptares Therapeutics, was published in the Nature journal on 17 July.

Researchers used a particle accelerator called the Diamond Light Source to understand the structure of CRF1. The X-ray machine’s powerful beams illuminated the protein’s structure, according to the Sunday Times, including a crevice that could become a new target for drug therapy.

The information gained from this study will be used to design small molecule drugs that fit into this new pocket to treat depression.

Speaking to the Sunday Times, Dr Fiona Marshall, Chief Scientific Officer at Heptares Therapeutics, said: “Now we know its shape, we can design a molecule that will lock into this crevice and block it so that CRF1 becomes inactive — ending the biochemical cascade that ends in stress.”

Writing on Diamond’s website, Dr. Andrew Dore, a senior scientist with Heptares added that the structure of the protein receptor “can be used as a template to solve closely related receptors that open up the potential for new drugs to treat a number of major diseases including Type 2 diabetes and osteoporosis”.

Thanks to Tracy Lindley for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.

North Pole now a lake

Instead of snow and ice whirling on the wind, a foot-deep aquamarine lake now sloshes around a webcam stationed at the North Pole. The meltwater lake started forming July 13, following two weeks of warm weather in the high Arctic. In early July, temperatures were 2 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit (1 to 3 degrees Celsius) higher than average over much of the Arctic Ocean, according to the National Snow & Ice Data Center.

Meltwater ponds sprout more easily on young, thin ice, which now accounts for more than half of the Arctic’s sea ice. The ponds link up across the smooth surface of the ice, creating a network that traps heat from the sun. Thick and wrinkly multi-year ice, which has survived more than one freeze-thaw season, is less likely sport a polka-dot network of ponds because of its rough, uneven surface.

July is the melting month in the Arctic, when sea ice shrinks fastest. An Arctic cyclone, which can rival a hurricane in strength, is forecast for this week, which will further fracture the ice and churn up warm ocean water, hastening the summer melt. The Arctic hit a record low summer ice melt last year on Sept. 16, 2012, the smallest recorded since satellites began tracking the Arctic ice in the 1970s.

http://www.livescience.com/38347-north-pole-ice-melt-lake.html

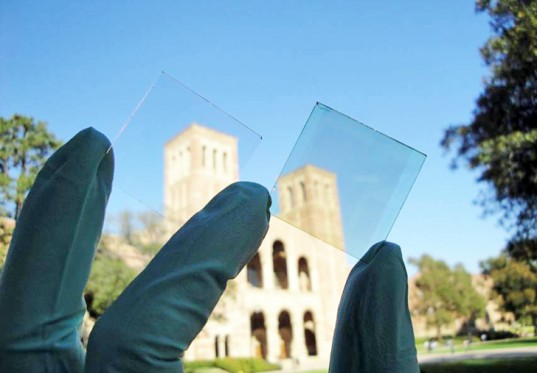

Electricity-Generating, Transparent Solar Cell Windows

A team from UCLA has developed a new transparent solar cell that has the ability to generate electricity while still allowing people to see outside. In short, they’ve created a solar power-generating window! Described as “a new kind of polymer solar cell (PSC)” that produces energy by absorbing mainly infrared light instead of traditional visible light, the photoactive plastic cell is nearly 70% transparent to the human eye—so you can look through it like a traditional window.

“These results open the potential for visibly transparent polymer solar cells as add-on components of portable electronics, smart windows and building-integrated photovoltaics and in other applications,” said study leader Yang Yang, a UCLA professor of materials science and engineering and also director of the Nano Renewable Energy Center at California NanoSystems Institute (CNSI). “Our new PSCs are made from plastic-like materials and are lightweight and flexible. More importantly, they can be produced in high volume at low cost.”

There are also other advantages to polymer solar cells over more traditional solar cell technologies, such as building-integrated photovoltaics and integrated PV chargers for portable electronics. In the past, visibly transparent or semitransparent PSCs have suffered low visible light transparency and/or low device efficiency because suitable polymeric PV materials and efficient transparent conductors were not well deployed in device design and fabrication. However that was something the UCLA team wished to address.

By using high-performance, solution-processed, visibly transparent polymer solar cells and incorporating near-infrared light-sensitive polymer and silver nanowire composite films as the top transparent electrode, the UCLA team found that the near-infrared photoactive polymer absorbed more near-infrared light but was less sensitive to visible light. This, in essence, created a perfect balance between solar cell performance and transparency in the visible wavelength region.

UCLA Develops Electricity-Generating, Transparent Solar Cell Windows

Thanks to Jody Troupe for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.

New research on adult neurogenesis shows that about 1,400 new brain cells are born every day, and about 80% of human brain cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus undergo renewal in adulthood

by Leonie Welberg

The question of whether adult neurogenesis occurs in the human hippocampus has been a hotly debated topic in neuroscience. In a study published in Cell, Frisén and colleagues now settle the debate by providing evidence that around 1,400 dentate gyrus cells are born in the human brain every day.

The authors made use of a birth-dating method that is based on the principle that 14C in the atmosphere is taken up by plants and — because humans eat plants and animals that eat plants — eventually also by humans. As 14C is incorporated into DNA during cell division, the 14C content of a cell is thought to reflect 14C levels in the atmosphere at the time of the birth of the cell. Importantly, atomic bomb testing in the 1950s and 1960s resulted in a spike in atmospheric 14C levels, and levels declined after 1963; this means that the level of 14C in cellular DNA can be used as a relatively precise marker of a cell’s birth date.

The authors applied the 14C birth-dating method to whole hippocampi dissected from post-mortem brains donated by individuals who were born in different years in the twentieth century. They separated neurons from non-neuronal hippocampal cells, purified the neuronal DNA and determined 14C levels. Neuronal 14C levels did not match atmospheric 14C levels in the individual’s birth year but were either higher (for people born before 1950) or lower (for people born after 1963), suggesting that at least some of the hippocampal cells were born after the year in which an individual was born.

Computer modelling of the data revealed that the best-fit model was one in which 35% of hippocampal cells showed such turnover, whereas the majority did not (that is, they were born during development). Assuming that, in humans, adult neurogenesis would take place in the dentate gyrus rather than in other hippocampal areas (as it does in rodents), and as the dentate gyrus contains about 44% of all hippocampal neurons, this model suggests that about 80% of human dentate gyrus cells undergo renewal in adulthood. This is in striking contrast to the scenario in mice, in which only ~10% of adult dentate gyrus neurons undergo renewal. The study further showed that there is very little decline in the level of hippocampal neurogenesis with ageing in humans, which is again in contrast to rodents.

It is now well established that adult-born neurons have a functional role in the mouse and rat dentate gyrus and olfactory bulb. A previous study using the same neuronal birth-dating method established that no adult neurogenesis takes place in the olfactory bulb and cortex in humans, but the new study has elegantly shown that the situation is different in the dentate gyrus. Whether the adult-born neurons have functional implications in humans remains a topic for future investigation.

http://www.nature.com/nrn/journal/v14/n8/full/nrn3548.html?WT.ec_id=NRN-201308

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.

New Human Body Part Discovered

The newest addition to human anatomy is just 15 microns thick, but its discovery will make eye surgery safer and simpler. Harminder Dua, a professor at the University of Nottingham, recently found a new layer in the human cornea, and he’s calling it Dua’s layer.

Dua’s layer sits at the back of the cornea, which previously had only five known layers. Dua and his colleagues discovered the new body part by injecting air into the corneas of eyes that had been donated for research and using an electron microscope to scan each separated layer.

The researchers now believe that a tear in Dua’s layer is the cause of corneal hydrops, a disorder that leads to fluid buildup in the cornea. According to Dua, knowledge of the new layer could dramatically improve outcomes for patients undergoing corneal grafts and transplants.

“This is a major discovery that will mean that ophthalmology textbooks will literally need to be re-written,” Dua says. “From a clinical perspective, there are many diseases that affect the back of the cornea which clinicians across the world are already beginning to relate to the presence, absence or tear in this layer.”

The study appears in the journal Ophthalmology.

http://www.popsci.com/science/article/2013-06/new-body-part-discovered-human-eye

Scientists discover why the chicken lost its penis.

Researchers have now unraveled the genetics behind why most male birds don’t have penises, just published in Current Biology.

[Ana Herrera et al, Developmental Basis of Phallus Reduction During Bird Evolution]

There are almost 10,000 species of birds and only around 3 percent of them have a penis. These include ducks, geese and swans, and large flightless birds like ostriches and emus. In fact, some ducks have helical penises that are longer than their entire bodies. But eagles, flamingos, penguins and albatrosses have completely lost their penises. So have wrens, gulls, cranes, owls, pigeons, hummingbirds and woodpeckers. Chickens still have penises, but barely—they’re tiny nubs that are no good for penetrating anything.

In all of these species, males still fertilise a female’s eggs by sending sperm into her body, but without any penetration. Instead, males and females just mush their genital openings together and he transfers sperm into her in a maneuver called the cloacal kiss.

To get to the root of this puzzle, researchers compared the embryos of chickens and ducks. Both types of birds start to develop a penis. But in chickens, the genital tubercle shrinks before the little guys hatch. And it’s because of a gene called Bmp4.

“There are lots of examples of animal groups that evolved penises, but I can think of only a bare handful that subsequently lost them,” says Diane Kelly from the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. “Ornithologists have tied themselves in knots trying to explain why an organ that gives males an obvious selective advantage in so many different animal species disappeared in most birds. But it’s hard to address a question on why something happens when you don’t know much about how it happens.”

That’s where Martin Cohn came in. He wanted to know the how. His team at the University of Florida studies how limbs and genitals develop across the animal kingdom, from the loss of legs in pythons to genital deformities in humans. “In a lab that thinks about genital development, one takes notice when a species that reproduces by internal fertilization lacks a penis,” says graduate student Ana Herrera.

By comparing the embryos of a Pekin duck and a domestic chicken, Herrera and other team members showed that their genitals start developing in the same way. A couple of small swellings fuse together into a stub called the genital tubercle, which gradually gets bigger over the first week or so. (The same process produces a mammal’s penis.)

In ducks, the genital tubercle keeps on growing into a long coiled penis, but in the chicken, it stops around day 9, while it’s still small. Why? Cohn expected to find that chickens are missing some critical molecule. Instead, his team found that all the right penis-growing genes are switched on in the chicken’s tubercle, and its cells are certainly capable of growing.

It never develops a full-blown penis because, at a certain point, its cells start committing mass suicide. This type of ‘programmed cell death’ occurs throughout the living world and helps to carve away unwanted body parts—for example, our hands have fingers because the cells between them die when we’re embryos. For the chicken, it means no penis. “It was surprising to learn that outgrowth fails not due to absence of a critical growth factor, but due to presence of a cell death factor,” says Cohn.

His team confirmed this pattern in other species, including an alligator (crocodilians are the closest living relatives of birds). In the greylag goose, emu and alligator, the tubercle continues growing into a penis, with very little cell death. In the quail, a member of the same order as chickens, the tubercle’s cells also experience a wave of death before the organ can get big.

This wave is driven by a protein called Bmp4, which is produced along the entire length of the chicken’s tubercle, but over much less of the duck’s. When Cohn’s team soaked up this protein, the tubercle’s cells stopped dying and carried on growing. So, it’s entirely possible for a chicken to grow a penis; it’s just that Bmp4 stops this from happening. Conversely, adding extra Bmp protein to a duck tubercle could stop it from growing into its full spiralling glory, forever fixing it as a chicken-esque stub.

Bmp proteins help to control the shape and size of many body parts. They’re behind the loss of wings in soldier ants and teeth of birds. Meanwhile, bats blocked these proteins to expand the membranes between their fingers and evolve wings.

They also affect the genitals of many animals. In ducks and geese, they create the urethra, a groove in the penis that sperm travels down (“If you think about it, that’s like having your urethra melt your penis,” says Kelly.) In mice, getting rid of the proteins that keep Bmp in check leads to tiny penises. Conversely, getting rid of the Bmp proteins leads to a grossly enlarged (and almost tumour-like) penis.

Penises have been lost several times in the evolution of birds. Cohn’s team have only compared two groups—the penis-less galliforms (chickens, quails and pheasants) and the penis-equipped anseriforms (swans, ducks and geese). What about the oldest group of birds—the ratites, like ostriches or emus? All of them have penises except for the kiwis, which lost theirs. And what about the largest bird group, the neoaves, which includes the vast majority of bird species? All of them are penis-less.

Maybe, all of these groups lost their penis in different ways. To find out, Herrera is now looking at how genitals develop in the neoaves. Other teams will no doubt follow suit. “The study will now allow us to more deeply explore other instances of penis loss and reduction in birds, to see whether there is more than one way to lose a penis,” says Patricia Brennan from the University of Massachussetts in Amherst.

And in at least one case, what was lost might have been regained. The cracids—an group of obscure South American galliforms—have penises unlike their chicken relatives. It might have been easy for them to re-evolve these body parts, since the galliforms still have all the genetic machinery for making a penis.

We now know how chickens lost their penises, but we don’t know why a male animal that needs to put sperm inside a female would lose the organ that makes this possible. Cohn’s study hints at one possibility—it could just be a side effect of other bodily changes. Bmp4 and other related proteins are involved in the evolution of many bird body parts, including the transition from scales to feathers, the loss of teeth, and variations in beak size. Perhaps one of these transformations changed the way Bmp4 is used in the genitals and led to shrinking penises.

There are many other possible explanations. Maybe a penis-less bird finds it easier to fly, runs a smaller risk of passing on sexually-transmitted infections, or is better at avoiding predators because he mates more quickly. Females might even be responsible. Male ducks often force themselves upon their females but birds without an obvious phallus can’t do that. They need the female’s cooperation in order to mate. So perhaps females started preferring males with smaller penises, so that they could exert more choice over whom fathered their chicks. Combinations of these explanations may be right, and different answers may apply to different groups.

Thanks to Dr. Lutter for bringing this to the It’s Interesting community.

http://www.oddly-even.com/2013/06/06/how-chickens-lost-their-penises-and-ducks-kept-theirs_/

http://news.yahoo.com/why-did-chicken-lose-penis-165408163.html