Nutt says politicians often have a “primitive, childish” way of thinking about drugs.

David Nutt is trying to develop a new recreational drug that he hopes will be taken up by millions of people around the world. No, the 62-year-old scientist isn’t “breaking bad.” In fact, he hopes to do good. His drug would be a substitute for alcohol, to create drinks that are just as intoxicating as beer or whiskey but less toxic. And it would come with an antidote to reverse its effects, allowing people to sober up instantly and drive home safely.

Nutt, a neuropsychopharmacologist at Imperial College London and a former top adviser to the British government on drug policy, says he has already identified a couple of candidates, which he is eager to develop further. “We know people like alcohol, they like the relaxation, they like the sense of inebriation,” Nutt says. “Why don’t we just allow them to do it with a drug that isn’t going to rot their liver or their heart?”

But when he presented the idea on a BBC radio program late last year and made an appeal for funding, many were appalled. A charity working on alcohol issues criticized him for “swapping potentially one addictive substance for another”; a commentator called the broadcast “outrageous.” News-papers likened his synthetic drug to soma, the intoxicating compound in Aldous Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World. Some of his colleagues dismissed the idea as scientifically unfeasible.

Nutt wasn’t surprised. As a fierce advocate of what he says are more enlightened, rational drug policies, he has been a lightning rod for a long time. Politicians, in Nutt’s view, make irrational decisions about drugs that help them win votes but cost society dearly. Drug policy is often based on the moral judgment that people should not use drugs, he says. Instead, it should reflect what science knows about the harms of different drugs—notably that many are far less harmful than legal substances such as alcohol, he says. The plan for a synthetic alcohol alternative is his own attempt to reduce the damage that drug use can wreak; he believes it could save millions of lives and billions of dollars.

Such views—and the combative way in which he espouses them—frequently land Nutt in fierce disputes. Newspaper commentators have called him “Professor Nutty” or “the dangerous professor.” In 2009, he was sacked from his position as chair of the United Kingdom’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, tasked with giving scientific advice to the home secretary, after he criticized a government decision on cannabis.

But in November 2013, he received the John Maddox Prize for standing up for science. “In circumstances that would have humiliated and silenced most people,” wrote neurobiologist Colin Blakemore, one of the judges, “David Nutt continued to affirm the importance of evidence in understanding the harms of drugs and in developing drug policy.”

Controversial comparisons

David Nutt does not look like a dangerous professor. Short and heavyset, he has a jovial, round face and an old-fashioned mustache; one could mistake him for a London taxi driver. He limps slightly, has a down-to-earth way of speaking, and laughs a lot when he talks. “He is a real personality,” says psychopharmacologist Rainer Spanagel of Heidelberg University in Germany. “You can be in a meeting and almost have a result, then he will come in an hour late, stir everything up, and in the end convince everyone of his position.”

Nutt says he realized at an early age that “understanding how the brain works is the most interesting and challenging question in the universe.” When he was a teenager, his father told him a story of how Albert Hofmann, the discoverer of LSD, took a dose of that drug and felt that the bike ride home took hours instead of minutes. “Isn’t that incredible, that a drug can change time?” he asks. On his first night as an undergraduate in Cambridge, he witnessed the powers of drugs again when he went drinking with fellow students. Two of them couldn’t stop. “I just watched them transform themselves. One of them started wailing and crying and the other became incredibly hostile.”

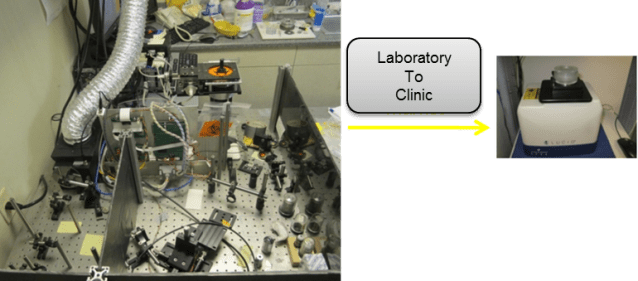

During his clinical training, Nutt says he treated many alcoholics but failed “to get anyone interested in how to reduce their addiction to the drug that was harming them.” He set out to answer that question, first in the United Kingdom, later as the chief of the Section of Clinical Science at the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, a job he held for 2 years. Today, he runs the department of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College, using modern imaging techniques to see what happens in the brain when people take drugs or develop an addiction.

But his biggest contribution to science, he says, was a discovery he made quite early in his career: that some molecules don’t just block receptors in the brain, but actually have the opposite effect of the molecules that normally stimulate them—and in doing so shut down a brain pathway. Nutt called these molecules contragonists, and he has made a second career out of being a bit of a contragonist himself, trying to calm society’s overexcited responses to the steady stream of alarming news about drugs.

Fictional affliction

In 2009, Nutt published an article in the Journal of Psychopharmacology comparing the harms from ecstasy with those caused by horse riding. Every 10,000th ecstasy pill is likely to hurt someone, he calculated, while an average horse enthusiast can expect a serious accident every 350 hours of riding. The sport, he concluded, was more dangerous than the notorious party drug. That “raises the critical question of why society tolerates—indeed encourages—certain forms of potentially harmful behaviour but not others such as drug use,” he added.

Politicians were not amused, and Nutt’s whimsical reference to a fictional affliction he called equine addiction syndrome, or “equasy,” did not help. In his book Drugs – Without the Hot Air, Nutt provided his account of a phone conversation he had with U.K. Home Secretary Jacqui Smith after the paper was published. (Smith calls it an “embroidered version” of their talk.)

Smith: “You can’t compare harms from a legal activity with an illegal one.”

Nutt: “Why not?”

“Because one’s illegal.”

“Why is it illegal?”

“Because it’s harmful.”

“Don’t we need to compare harms to determine if it should be illegal?”

“You can’t compare harms from a legal activity with an illegal one.”

Nutt says this kind of circular logic crops up again and again when he discusses recreational drugs with politicians. “It’s what we would call ‘splitting’ in psychiatric terms: this primitive, childish way of thinking things are either good or bad,” he says.

He’s often that outspoken. He likens the way drug laws are hampering legitimate scientific research, for instance into medical applications for psychedelic compounds, to the church’s actions against Galileo and Copernicus. When the United Kingdom recently banned khat, a plant containing a stimulant that’s popular among people from the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, he compared the decision with banning cats. And he accuses the Russian government of deliberately using alcohol to weaken the opposition. “However miserable they are, however much they hate their government and their country, they will just drink until they kill themselves, so they won’t protest,” he says.

But it’s his stance on cannabis that got him sacked. In early 2009, ignoring advice from Nutt’s advisory council, Smith upgraded cannabis from class C to class B, increasing the maximum penalty for possession from 2 to 5 years in prison. A few months later, Nutt criticized the decision in a public lecture, arguing that “overall, cannabis use does not lead to major health problems” and that tobacco and alcohol were more harmful. When media reported the remarks, Alan Johnson, who succeeded Smith as home secretary in mid-2009, asked him to resign. “He was asked to go because he cannot be both a government adviser and a campaigner against government policy,” Johnson wrote in a letter in The Guardian.

Nutt did not go quietly. With financial help from a young hedge fund manager, Toby Jackson, he set up a rival body, the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs, “to ensure that the public can access clear, evidence based information on drugs without interference from political or commercial interest.” Politics have skewed not just drug laws but research itself, he argues. “If you want to get money from the U.S. government to work on a drug, you have to prove it damages the brain,” he says.

One of his favorite examples is a paper that Science published in September 2002. The study, led by George Ricaurte at Johns Hopkins University, seemed to show that monkeys given just two or three doses of ecstasy, chemically known as MDMA, developed severe brain damage. The finding suggested that “even individuals who use MDMA on one occasion may be at risk for substantial brain injury,” the authors wrote. The paper received massive media attention, but it was retracted a year later after the authors discovered that they had accidentally injected the animals not with MDMA but with methamphetamine, also known as crystal meth, which was already known to have the effects seen in the monkeys. Nutt says the mistake should have been obvious from the start because the data were “clearly wrong” and “scientifically implausible.” “If that result was true, then kids would have been dropping dead from Parkinson’s,” he says.

Some resent this combative style. “He is a polarizing figure and the drug policy area is polarized enough,” says Jonathan Caulkins, a professor of public policy at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. But Jürgen Rehm, an epidemiologist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada, says Nutt has helped stimulate debates that were long overdue. “You don’t get to be on the front page of The Lancet and The New York Times unless you sharpen your arguments a little bit,” Rehm says. “I can live with that.”

Ranking the drugs

In 2010, Nutt sparked a new firestorm when he published another comparison: a Lancet paper ranking drugs according to the harm they cause. Nutt and other experts scored a long list of drugs on 16 criteria, nine related to the user, such as death from an overdose or wrecked relationships, and seven related to society, such as drug-fueled violence and economic costs. In the end, every drug was given a score between 0 and 100 to indicate its overall harm. Alcohol came out on top, ahead of heroin; mushrooms and ecstasy were at the low end.

Critics said the study’s methodology was flawed because it didn’t address drug interactions and the social context of drug use. “For instance, the number of fatalities caused by excessive alcohol use is going to depend in part on gun control laws,” says Caulkins, who calls the whole idea of expressing drug harm as a single number “embarrassing.”

Caulkins adds that even if a perfect ranking of drug harms were possible, it wouldn’t mean that politicians should put the tightest control measures on the most harmful drugs. Suppose drug A is more harmful to the individual and society than drug B, he says, but impurities in drug A, when illegally produced, can lead to potentially fatal organ failure while they just taste bad in drug B. If you were going to prohibit only one of the two drugs, it should be drug B, he says, even though it causes less harm per se, because criminalizing drug A would lead to a more dangerous product and more deaths. Nutt’s ranking of drugs, he says, is “a pseudoscientific exercise which is trying to take control of the policy process from a technocratic perspective in a way that isn’t even sound.”

Other scientists defended the paper. Using Nutt’s harm scales, “flawed and limited as they may be, would constitute a quantum leap of progress towards evidence-based and more rational drug policy in Canada and elsewhere,” two Canadian drug scientists wrote in Addiction. Regardless of its quality, the paper has been hugely influential, Rehm says. “Everyone in the E.U. knows that paper, whether they like it or not. There is a time before that paper and a time after it appeared.”

Nutt says his comparisons are an essential first step on the way to more evidence-based drug policies that seek to reduce harm rather than to moralize. The best option would be a regulated market for alcohol and all substances less harmful to the user than alcohol, he argues.

That scenario, under which only heroin, crack cocaine, and methamphetamine would remain illegal, seems unlikely to become a reality. But Nutt says he can already see more rational policies taking hold. Recently, Uruguay and the U.S. states of Colorado and Washington legalized the sale of recreational cannabis, going a step further than the Netherlands, which stopped enforcing laws on the sale and possession of small amounts of soft drugs decades ago. Nutt was also happy to read President Barack Obama’s recent comment that cannabis is less harmful than alcohol. “At last, a politician telling the truth,” he says. “I’ll warn him though—I was sacked for saying that.”

New Zealand, meanwhile, passed a law in 2013 that paves the way for newly invented recreational drugs to be sold legally if they have a “low risk” of harming the user. Nutt, who has advised the New Zealand government, is delighted by what he calls a “rational revolution in dealing with recreational drugs.” The main problem now, he says, is establishing new drugs’ risks—which is difficult because New Zealand does not allow them to be tested on animals—and deciding what “low risk” actually means. “I told them the threshold should be if it is safer than alcohol,” he says. “They said: ‘Oh my god, that is going to be far too dangerous.'”

Safer substitute

Nutt agrees that alcohol is now one of the most dangerous drugs on the market—which is why he’s trying to invent a safer substitute. The World Health Organization estimates that alcohol—whose harms range from liver cirrhosis, cancer, and fetal alcohol syndrome to drunk driving and domestic violence—kills about 2.5 million people annually. “When I scan the brains of people with chronic alcohol dependence, many have brains which are more damaged than those of people with Alzheimer’s,” Nutt says.

In a paper published this month in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, Nutt and Rehm summarize the top six interventions that governments should consider to reduce the harms of alcohol, such as minimum prices and restrictions on the places that can sell hard liquor. They also argue that governments should support the development of alternatives. Nutt points to e-cigarettes—devices that heat and vaporize a nicotine solution—as a model. “In theory, electronic cigarettes could save 5 million lives a year. That is more than [the death toll from] AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and meningitis put together,” he says. “I would argue that the e-cigarette is going to be the greatest health invention since vaccination.”

Can an alcohol alternative do the same? “I think that idea is utopian,” says Spanagel, the German psychopharmacologist. One reason is that researchers have recently developed a much more complex picture of what ethanol, as chemists call it, actually does. Twenty years ago, they thought that once it reached the brain, alcohol elicited its many effects by infiltrating the membranes of neurons there and changing their properties. “Now we know that’s nonsense. You would have to drink 5 liters of schnapps for that to happen,” Spanagel says.

In fact, scientists have learned that alcohol, like other drugs, interacts with the receptors for certain neurotransmitters. But unlike other drugs, it acts on a wide range of them, including receptors for GABA, NMDA, serotonin, and acetylcholine. That will make it hard to find a substance to emulate most of alcohol’s wanted effects while avoiding the unwanted ones, Spanagel predicts.

Nutt is concentrating on the GABA system—the most important inhibitory system in mammalian brains. Alcohol activates GABA receptors, effectively quieting the brain and leading to the state of relaxation many people seek. Nutt has sampled some compounds that target GABA receptors and was pleasantly surprised. “After exploring one possible compound I was quite relaxed and sleepily inebriated for an hour or so, then within minutes of taking the antidote I was up giving a lecture with no impairment whatsoever,” he wrote in a recent article.

But he wants to go one step further. “We know that different subtypes of GABA mimic different effects of alcohol,” he says. Nutt combed the scientific literature and patents for compounds targeting specific GABA receptors, and, in an as-yet unpublished report that he shared with Science, he identifies several molecules that he says fit the bill. Compounds targeting subtypes of the GABAA receptor called alpha2 and alpha3 are particularly promising, he says. Some of these molecules were dropped as therapeutic drug candidates precisely because they had side effects similar to alcohol intoxication.

Gregg Homanics, an alcohol researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, is skeptical that another substance could mimic all the positive effects of alcohol. “You could come up with a drug that might make you feel good. But is it going to be the same good feeling as alcohol? I doubt that.” Such a drug might have downsides of its own, warns Andreas Heinz, an addiction researcher at Charité University Medicine Berlin. It could still turn out to be addictive or to harm a small proportion of the population. “There is an advantage when you have known drugs for hundreds of years and you know exactly what they do,” he says.

Still, Nutt’s appearance on the BBC radio program attracted new investors, ranging “from Ukrainian brewers to American hedge funds,” he says, and Imperial Innovations, a company that provides technology transfer services, is working with him “to consider a range of options for taking the research forward,” a spokesperson says. “We think we have enough funding now to take a substance all the way to the market,” Nutt says—in fact, he hopes to be able to offer the first cocktails for sale in as little as a year from now.

Even a very good alcohol substitute would face obstacles. Many people won’t forsake drinks they have long known and loved—such as beer, wine, and whiskey—for a new chemical, Spanagel says. The idea will also trigger all kinds of political and regulatory debates, Rehm says. “How will such a new drug be seen? Will you be able to buy it in the supermarket? In the pharmacy? Will society accept it?”

Whatever the outcome, Nutt’s quest for a safer drink has already made people think about alcohol in a new way, Rehm adds. “It’s provocative in the best sense of the word.” Much the same could be said of the scientist who thought it up.

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/343/6170/478.full