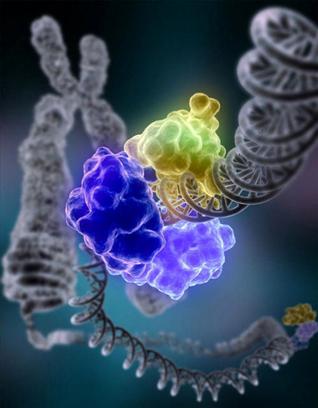

When the human genome was sequenced a decade ago, scientists hailed the feat as a technical tour de force — but they also knew it was just a start. The “HHA000078” DNA blueprint was finally laid bare, but no one knew what it all meant.

Now an international team has taken the crucial next step by delivering the first in-depth report on what the endless loops and lengths of DNA inside our cells are up to.

The findings, detailed Wednesday in more than two dozen reports in the journals Nature and Science and other publications, do much more than provide a straightforward list of genes. By creating a complicated catalog of all the places along our DNA strands that are biochemically active, they offer new insight into how genes work and influence common diseases. They also upend the conventional wisdom that most of our DNA serves no useful purpose.

Defining this hive of activity is essential, scientists said, because it transforms our picture of the human blueprint from a static list of 3 billion DNA building blocks into the dynamic master-regulator that it is. The revelations will be key to understanding how genes are controlled so that they leap into action at precisely the right time and place in our bodies, allowing a whole human being to develop from a single fertilized egg. In addition, they will help explain how the carefully choreographed process can go awry, triggering birth defects, diseases and aging.

“The human genome was a bit like getting ‘War and Peace’ in Russian: It’s a great book containing all of human experience, but [if] I don’t know any Russian it’s very hard to read,” said Ewan Birney, a computational biologist at the European Bioinformatics Institute in England who coordinated the analysis for the project. Now scientists are on their way to having the translation, he said.

More than 400 scientists have conducted upward of 1,600 experiments over five years to produce the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements, which goes by the nickname ENCODE. If graphically presented, the data it has generated so far would cover a poster 30 kilometers long and 16 meters high, Birney estimated.

Already, it is revealing surprises.

The results overturn old ideas that the bulk of DNA in our cells is useless — albeit inoffensive — junk just carried along for the evolutionary ride. Back in 2003, when the human genome was finished, scientists estimated that less than 2% carries instructions for making proteins, which become physical structures in our bodies and do the myriad jobs inside cells. The conventional wisdom was that the rest of the genetic code didn’t do very much.

But the new analysis shows that more than 80% of the human genome is active in at least one biological process that the ENCODE team measured. Nearly all of it could turn out to be active when the data are more complete.

A huge chunk of that activity is wrapped up with gene regulation — dictating whether the instructions each gene carries for making a unique protein will be executed or not. Such regulation is key, because pretty much every cell in the human body carries the entire set of 21,000 protein-making genes. To adopt its unique identity, each cell — be it one in the pancreas that makes insulin or one in the skin making pigment or hair — must activate only a subset of them.

Using an array of laboratory methods and tissue from more than 150 types of human cells, the scientists found and mapped millions of DNA sites that act as “switches” — turning genes off or on in one cell or another, at various times and intensities. The switches flip when master-regulator proteins bind to them, or when chemical “tags” are attached to them by enzymes.

“There’s way more switches than we ever imagined,” Birney said.

Some of the switches are right where scientists would expect them to be: close to the genes they control. But some are extremely far away, the researchers found.

Though that was unexpected, it makes sense, said molecular geneticist Joseph Ecker of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, who was not on the ENCODE team but wrote a commentary accompanying the main report in Nature.

“We draw DNA out as this long, linear thing where you can read from one end to the other, but the reality in the cell is that the molecule is folded tightly and compactly,” Ecker said. With the DNA scrunched up like a hairball, places far apart on a strand can end up close to each other in physical space.

The mass of data from the project is already proving a boon for scientists exploring the genetics of common disorders such as cancer and diabetes, which up till now has been a largely frustrating effort.

“Now that we have the switches, we can start to understand why a combination of DNA variants might increase the chances of a particular disease,” said ENCODE researcher Dr. Bradley Bernstein, a pathologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston and the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Mass.

Past efforts had focused on screening the genomes of people with various diseases to look for patterns of DNA differences, said Dr. John Stamatoyannopoulos, a genome scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle and member of the ENCODE team. Researchers found hundreds or thousands of variants associated with common diseases, but only about 5% of them were in genes, and it was unclear what all the other ones did.

Many of these variants, it now turns out, were located in places involved in regulating genes. For instance, the team discovered that one variant associated with platelet count was within a stretch of DNA that controls a gene involved in platelet production.

“It isn’t just noise,” Stamatoyannopoulos said of the baffling results from earlier studies.

http://www.latimes.com/news/science/la-sci-dna-encode-20120906,0,7798745.story

![DNA-To-Store-Data-In-Future-Scientists-Were-Able-To-Convert-A-Book-Into-A-Strand-Of-Genetic-Code-[Scientist][2]](https://its-interesting.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/dna-to-store-data-in-future-scientists-were-able-to-convert-a-book-into-a-strand-of-genetic-code-scientist2.jpg?w=640)