New research explains how abstract benefits of exercise—from reversing depression to fighting cognitive decline—might arise from a group of key molecules.

While our muscles pump iron, our cells pump out something else: molecules that help maintain a healthy brain. But scientists have struggled to account for the well-known mental benefits of exercise, from counteracting depression and aging to fighting Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Now, a research team may have finally found a molecular link between a workout and a healthy brain.

Much exercise research focuses on the parts of our body that do the heavy lifting. Muscle cells ramp up production of a protein called FNDC5 during a workout. A fragment of this protein, known as irisin, gets lopped off and released into the bloodstream, where it drives the formation of brown fat cells, thought to protect against diseases such as diabetes and obesity. (White fat cells are traditionally the villains.)

While studying the effects of FNDC5 in muscles, cellular biologist Bruce Spiegelman of Harvard Medical School in Boston happened upon some startling results: Mice that did not produce a so-called co-activator of FNDC5 production, known as PGC-1α, were hyperactive and had tiny holes in certain parts of their brains. Other studies showed that FNDC5 and PGC-1α are present in the brain, not just the muscles, and that both might play a role in the development of neurons.

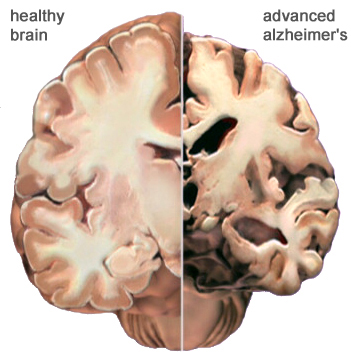

Spiegelman and his colleagues suspected that FNDC5 (and the irisin created from it) was responsible for exercise-induced benefits to the brain—in particular, increased levels of a crucial protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is essential for maintaining healthy neurons and creating new ones. These functions are crucial to staving off neurological diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. And the link between exercise and BDNF is widely accepted. “The phenomenon has been established over the course of, easily, the last decade,” says neuroscientist Barbara Hempstead of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, who was not involved in the new work. “It’s just, we didn’t understand the mechanism.”

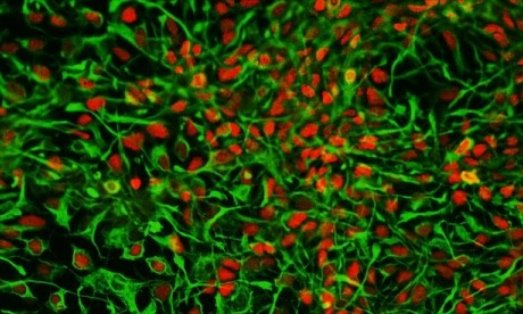

To sort out that mechanism, Spiegelman and his colleagues performed a series of experiments in living mice and cultured mouse brain cells. First, they put mice on a 30-day endurance training regimen. They didn’t have to coerce their subjects, because running is part of a mouse’s natural foraging behavior. “It’s harder to get them to lift weights,” Spiegelman notes. The mice with access to a running wheel ran the equivalent of a 5K every night.

Aside from physical differences between wheel-trained mice and sedentary ones—“they just look a little bit more like a couch potato,” says co-author Christiane Wrann, also of Harvard Medical School, of the latter’s plumper figures—the groups also showed neurological differences. The runners had more FNDC5 in their hippocampus, an area of the brain responsible for learning and memory.

Using mouse brain cells developing in a dish, the group next showed that increasing the levels of the co-activator PGC-1α boosts FNDC5 production, which in turn drives BDNF genes to produce more of the vital neuron-forming BDNF protein. They report these results online today in Cell Metabolism. Spiegelman says it was surprising to find that the molecular process in neurons mirrors what happens in muscles as we exercise. “What was weird is the same pathway is induced in the brain,” he says, “and as you know, with exercise, the brain does not move.”

So how is the brain getting the signal to make BDNF? Some have theorized that neural activity during exercise (as we coordinate our body movements, for example) accounts for changes in the brain. But it’s also possible that factors outside the brain, like those proteins secreted from muscle cells, are the driving force. To test whether irisin created elsewhere in the body can still drive BDNF production in the brain, the group injected a virus into the mouse’s bloodstream that causes the liver to produce and secrete elevated levels of irisin. They saw the same effect as in exercise: increased BDNF levels in the hippocampus. This suggests that irisin could be capable of passing the blood-brain barrier, or that it regulates some other (unknown) molecule that crosses into the brain, Spiegelman says.

Hempstead calls the findings “very exciting,” and believes this research finally begins to explain how exercise relates to BDNF and other so-called neurotrophins that keep the brain healthy. “I think it answers the question that most of us have posed in our own heads for many years.”

The effect of liver-produced irisin on the brain is a “pretty cool and somewhat surprising finding,” says Pontus Boström, a diabetes researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. But Boström, who was among the first scientists to identify irisin in muscle tissue, says the work doesn’t answer a fundamental question: How much of exercise’s BDNF-promoting effects come from irisin reaching the brain from muscle cells via the bloodstream, and how much are from irisin created in the brain?

Though the authors point out that other important regulator proteins likely play a role in driving BDNF and other brain-nourishing factors, they are focusing on the benefits of irisin and hope to develop an injectable form of FNDC5 as a potential treatment for neurological diseases and to improve brain health with aging.

http://news.sciencemag.org/biology/2013/10/how-exercise-beefs-brain

Thanks to Dr. Rajadhyaksha for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.