After most pregnancies, the placenta is thrown out, having done its job of nourishing and supporting the developing baby.

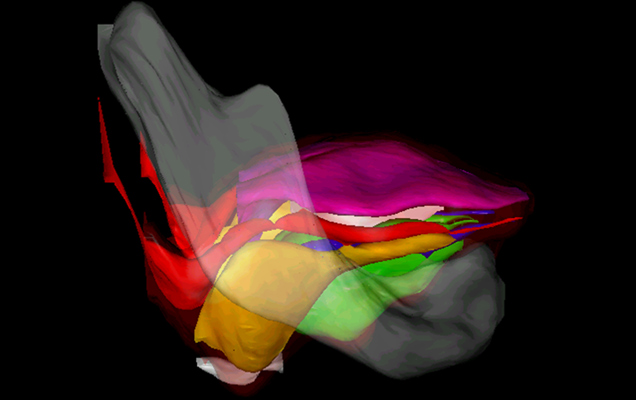

But a new study raises the possibility that analyzing the placenta after birth may provide clues to a child’s risk for developing autism. The study, which analyzed placentas from 217 births, found that in families at high genetic risk for having an autistic child, placentas were significantly more likely to have abnormal folds and creases.

“It’s quite stark,” said Dr. Cheryl K. Walker, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the Mind Institute at the University of California, Davis, and a co-author of the study, published in the journal Biological Psychiatry. “Placentas from babies at risk for autism, clearly there’s something quite different about them.”

Researchers will not know until at least next year how many of the children, who are between 2 and 5, whose placentas were studied will be found to have autism. Experts said, however, that if researchers find that children with autism had more placental folds, called trophoblast inclusions, visible after birth, the condition could become an early indicator or biomarker for babies at high risk for the disorder.

“It would be really exciting to have a real biomarker and especially one that you can get at birth,” said Dr. Tara Wenger, a researcher at the Center for Autism Research at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not involved in the study.

The research potentially marks a new frontier, not only for autism, but also for the significance of the placenta, long considered an after-birth afterthought. Now, only 10 percent to 15 percent of placentas are analyzed, usually after pregnancy complications or a newborn’s death.

Dr. Harvey J. Kliman, a research scientist at the Yale School of Medicine and lead author of the study, said the placenta had typically been given such little respect in the medical community that wanting to study it was considered equivalent to someone in the Navy wanting to scrub ships’ toilets with a toothbrush. But he became fascinated with placentas and noticed that inclusions often occurred with births involving problematic outcomes, usually genetic disorders.

He also noticed that “the more trophoblast inclusions you have, the more severe the abnormality.” In 2006, Dr. Kliman and colleagues published research involving 13 children with autism, finding that their placentas were three times as likely to have inclusions. The new study began when Dr. Kliman, looking for more placentas, contacted the Mind Institute, which is conducting an extensive study, called Marbles, examining potential causes of autism.

“This person came out of the woodwork and said, ‘I want to study trophoblastic inclusions,’ ” Dr. Walker recalled. “Now I’m fairly intelligent and have been an obstetrician for years and I had never heard of them.”

Dr. Walker said she concluded that while “this sounds like a very smart person with a very intriguing hypothesis, I don’t know him and I don’t know how much I trust him.” So she sent him Milky Way bar-size sections of 217 placentas and let him think they all came from babies considered at high risk for autism because an older sibling had the disorder. Only after Dr. Kliman had counted each placenta’s inclusions did she tell him that only 117 placentas came from at-risk babies; the other 100 came from babies with low autism risk.

She reasoned that if Dr. Kliman found that “they all show a lot of inclusions, then maybe he’s a bit overzealous” in trying to link inclusions to autism. But the results, she said, were “astonishing.” More than two-thirds of the low-risk placentas had no inclusions, and none had more than two. But 77 high-risk placentas had inclusions, 48 of them had two or more, including 16 with between 5 and 15 inclusions.

Dr. Walker said that typically between 2 percent and 7 percent of at-risk babies develop autism, and 20 percent to 25 percent have either autism or another developmental delay. She said she is seeing some autism and non-autism diagnoses among the 117 at-risk children in the study, but does not yet know how those cases match with placental inclusions.

Dr. Jonathan L. Hecht, associate professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School, said the study was intriguing and “probably true if it finds an association between these trophoblast inclusions and autism.” But he said that inclusions were the placenta’s way of responding to many kinds of stress, so they might turn out not to be specific enough to predict autism.

Dr. Kliman calls inclusions a “check-engine light, a marker of: something’s wrong, but I don’t know what it is.”

That’s how Chris Mann Sullivan sees it, too. Dr. Sullivan, a behavioral analyst in Morrisville, N.C., was not in the study, but sent her placenta to Dr. Kliman after her daughter Dania, now 3, was born. He found five inclusions. Dr. Sullivan began intensive one-on-one therapy with Dania, who has not been given a diagnosis of autism, but has some relatively mild difficulties.

“What would have happened if I did absolutely nothing, I’m not sure,” Dr. Sullivan said. “I think it’s a great way for parents to say, ‘O.K., we have some risk factors; we’re not going to ignore it.’ ”

Thanks to Dr. Rajadhyaksha for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.