The following nine drawings were made a half century ago by an artist under the influence of LSD, or acid, during an experiment designed to investigate the psychedelic drug’s effects . The unnamed artist was given two 50-microgram doses of LSD, one 65 minutes after the other, and had access to an activity box full of crayons and pencils. The subject of his art was the assisting doctor who administered the drug. Though records of the identity of the principal researcher have been lost, it was probably a University of California-Irvine psychiatrist, Oscar Janiger. Janiger, known for his LSD research, died in 2001.

“I believe the pictures are from an experiment conducted by the psychiatrist Oscar Janiger starting in 1954 and continuing for seven years, during which time he gave LSD to over 100 professional artists and measured its effects on their artistic output and creative ability. Over 250 drawings and paintings were produced,” said Andrew Sewell, a physician at Yale School of Medicine who has done research on psychedelic drugs.

During the experiment, the artist reported how he felt the acid was affecting him as he drew each sketch. To add some modern understanding of how LSD affects the brain to the artist’s scrawlings, we reached out to Sewell and a few other psychologists for insight on what was probably going on in the artist’s head.

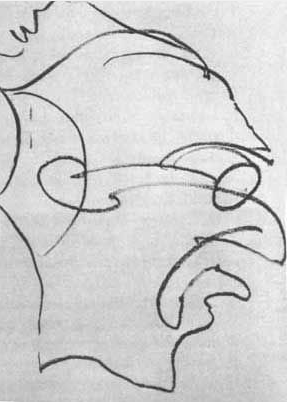

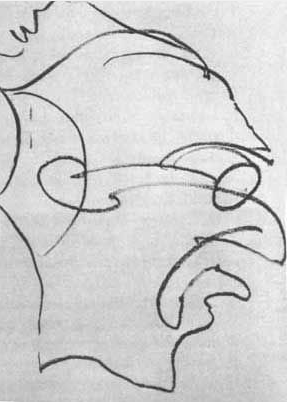

Attending doctor’s observations: The first drawing is done 20 minutes after the first dose. Patient chooses to start drawing with charcoal.

Artist’s Comment: “Condition normal … no effect from the drug yet.”

Analysis: According to Duncan Blewett and Nick Chwelos, psychiatrists who conducted extensive LSD research in the 1950s, symptoms set in sometime between 15 minutes and two hours after taking the drug, and usually after about half an hour.

“The period of waiting for the drug to have an effect is important, since the psychological set which is established at that time can determine much of what follows,” they wrote in 1959 in “The Handbook for the Therapeutic Use of LSD.” “Boredom on the part of either the subject or therapist must be avoided. The therapist should also aim at preventing the development of a pattern in which the subject is waiting intently for any change which might be ascribed to the drug. Finally, the therapist should be particularly careful to prevent the build-up of apprehension in the subject.”

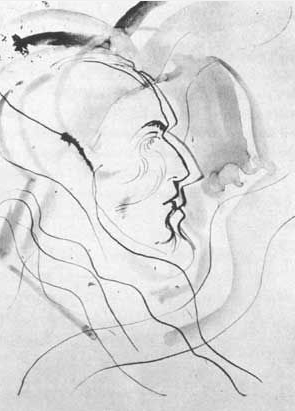

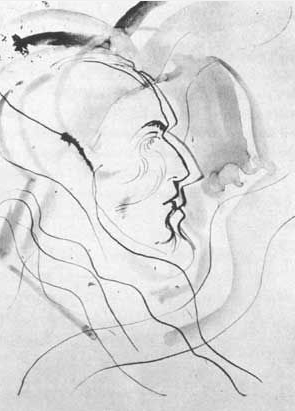

Observations: Eighty-five minutes after first dose, 20 minutes after second dose. The patient seems euphoric.

Artist’s comment: “I can see you clearly, so clearly. This… you… it’s all … I’m having a little trouble controlling this pencil. It seems to want to keep going.”

Analysis: Research suggests that “LSD experiences may wildly enhance artists’ creative potential without necessarily enhancing the mechanisms needed to harness that creativity toward artistic ends,” anthropologist Marlene Dobkin de Rios wrote in her book “LSD, Spirituality and the Creative Process” (Park Street Press, 2003).

In other words, artistic technique doesn’t necessarily keep pace with the flow of ideas during an acid trip. But practice can help. “With practice, most of Janinger’s artists became adept at working under its influence,” said Sewell.

Observations: Two hours, 30 minutes after first dose, 85 minutes after second dose. The patient appears very focused on the business of drawing.

Artist’s comment: “Outlines seem normal, but very vivid everything is changing color. My hand must follow the bold sweep of the lines. I feel as if my consciousness is situated in the part of my body that’s now active my hand, my elbow… my tongue.”

Analysis: “Janiger believed that LSD favored the prepared mind and that formal artist training would be the best preparation to handle the creative explosion that came from LSD use,” Sewell told Life’s Little Mysteries. “He ultimately concluded that the art was no better or worse, but it was different. LSD is not a creativity tool, nor does it unlock creativity. Rather, it makes accessible parts of the individual not normally available.

“People who are already artists or craftsmen when they take LSD benefit from it, but uncreative people are not suddenly made so. He also concluded that although LSD could be a powerful instrument to free the artist from conceptual ruts, it did little to facilitate the development of technique.”

Observations: Two hours, 32 minutes after first dose. The patient seems gripped by his pad of paper.

Artist’s comment: “I’m trying another drawing. The outlines of the model are normal, but now those of my drawing are not. The outline of my hand is going weird, too. It’s not a very good drawing, is it? I give up I’ll try again …”

Analysis: When under the influence of LSD, “some people describe a kind of frustration with language or art that does not allow for a 3-D experience ,” Erika Dyck, medical historian and author of the book “Psychedelic Psychiatry” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), told Life’s Little Mysteries.

Observations: Two hours, 35 minutes after first dose. The patient follows quickly with another drawing. Upon completing it, he starts laughing, then becomes startled by something on the floor.

Artist’s comment: “I’ll do a drawing in one flourish … without stopping … one line, no break!’

Analysis: “Paintings produced under the influence of LSD tend to have the following characteristics,” Sewell said. “The artist’s work tends to fill all available space and resists being contained within its borders; alternately, figures may shrink or become embedded in a matrix. Figure and ground becomes a continuum, with less differentiation between object and subject. The object is in continuous movement, with greater vibrancy and motion. There is greater intensity of color and light. There is an elimination of detail and extraneous elements. Objects may be depicted symbolically or as abstractions. They may also become more fragmented, disorganized, and distorted.”

Observations: Two hours, 45 minutes after first dose. The patient tries to climb into the activity box, and is generally agitated responds slowly to the suggestion that he might like to draw some more. He has become largely nonverbal. Patient mumbles inaudibly to a tune (sounds like “Thanks for the Memory”). He changes medium to tempera.

Artist’s comment: “I am … everything is … changed … They’re calling … your face … interwoven … who is…”

Analysis: “Common reactions to LSD include a retreat into often less verbal forms of communication, more abstract ideas,” Dyck said, “or, at the very least, ideas that are difficult to describe or even paint in a conventional way.”

Observations: Four hours, 25 minutes after the first dose. The patient retreated to the bunk, spending approximately two hours lying, waving his hands in the air. His return to the activity box is sudden and deliberate, changing media to pen and watercolor. He makes the last half-a-dozen strokes of the drawing while running back and forth across the room.

Artist’s comment: “This will be the best drawing, like the first one, only better. If I’m not careful I’ll lose control of my movements, but I won’t, because I know, I know.” [Repeats “I know” several more times.]

Analysis: A group of Italian scientists led by G. Tonini also investigated LSD-influenced art making. “When done under the influence of these drugs, [the art] reflected psychopathological manifestations markedly similar to those observed in schizophrenia,” Tonini wrote in 1955.

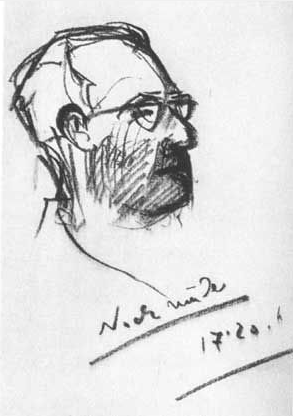

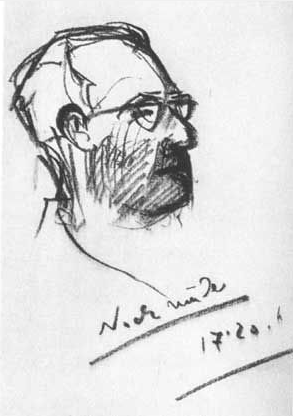

Observations: Five hours, 45 minutes after the first dose. The patient continues to move about the room, intersecting the space in complex variations. It’s an hour and a half before he settles down to draw again he appears to be over the effects of the drug.

Artist’s comment: “I can feel my knees again; I think it’s starting to wear off. This is a pretty good drawing this pencil is mighty hard to hold.” (He is holding a crayon.)

Analysis: “LSD can give people a different perspective than the one they usually have,” Sewell said. “What they do with that is up to them. It is not a ‘creativity pill.’ The best analogy is travel. It can broaden the mind … or not. It depends where you go and what you do there.”

Observations: Eight hours after the first dose. The patient sits on the bunk bed. He reports that the intoxication has worn off except for the occasional distorting of our faces. We ask for a final drawing, which he performs with little enthusiasm.

Artist’s comment: “I have nothing to say about this last drawing. It is bad and uninteresting. I want to go home now.”

Analysis: In a later interview, Janiger said that after the artists in his studies were done tripping, “99 percent expressed the notion that this was an extraordinary, valuable tool for learning about art and the way one learns about painting or drawing. Almost all personally agreed they would take it again.”

“In 1971, Carl Hertzel, a professor of art history at Pitzer College in Claremont, undertook a stylistic assessment of the artwork, which was published by the Lang Art Gallery also in 1971,” Sewell said. “In 1986, 25 of the original artists participated in an exhibit called, ‘The Enchanted Loom: LSD and Creativity’ in which they commented on their own artwork, mostly positively.”

http://www.livescience.com/33166-slideshow-scientists-analyze-drawings-acid-trip-artist.html