In 2004, the Ministry of Health in China banned this procedure due to lack of data on long term outcomes and growing outrage in Western media over ethical issues about whether the patients were fully aware of the risks.

However, some doctors were allowed to continue to perform it for research purposes—and recently, a Western medical journal even published a new study of the results. In 2007, The Wall Street Journal detailed the practice of a physician who claimed he performed 1000 such procedures to treat mental illnesses such as depression, schizophrenia and epilepsy, after the ban in 2004; the surgery for addiction has also since been done on at least that many people.

The November publication has generated a passionate debate in the scientific community over whether such research should be published or kept outside the pages of reputable scientific journals, where it may find undeserved legitimacy and only encourage further questionable science to flourish.

The latest study is the third published since 2003 in Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, which isn’t the only journal chronicling results from the procedure, which is known as ablation of the nucleus accumbens. In October, the journal World Neurosurgery also published results from the same researchers, who are based at Tangdu Hospital in Xi’an.

The authors, led by Guodong Gao, claim that the surgery is “a feasible method for alleviating psychological dependence on opiate drugs.” At the same time, they report that more than half of the 60 patients had lasting side effects, including memory problems and loss of motivation. Within five years, 53% had relapsed and were addicted again to opiates, leaving 47% drug free.

(MORE: Addicted: Why We Get Hooked)

Conventional treatment only results in significant recovery in about 30-40% of cases, so the procedure apparently improves on that, but experts do not believe that such a small increase in benefit is worth the tremendous risk the surgery poses. Even the most successful brain surgeries carry risk of infection, disability and death since opening the skull and cutting brain tissue for any reason is both dangerous and unpredictable. And the Chinese researchers report that 21% of the patients they studied experienced memory deficits after the surgery and 18% had “weakened motivation,” including at least one report of lack of sexual desire. The authors claim, however, that “all of these patients reported that their [adverse results] were tolerable.” In addition, 53% of patients had a change in personality, but the authors describe the majority of these changes as “mildness oriented,” presumably meaning that they became more compliant. Around 7%, however, became more impulsive.

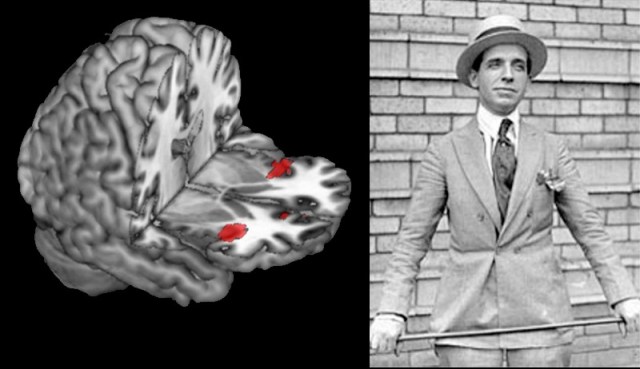

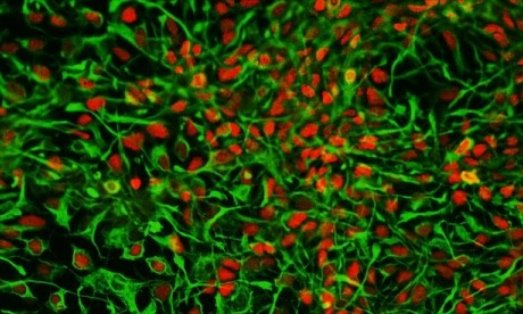

The surgery is actually performed while patients are awake in order to minimize the chances of destroying regions necessary for sensation, consciousness or movement. Surgeons use heat to kill cells in small sections of both sides of the brain’s nucleus accumbens. That region is saturated with neurons containing dopamine and endogenous opioids, which are involved in pleasure and desire related both to drugs and to ordinary experiences like eating, love and sex.

(MORE: A Drug to End Drug Addiction)

In the U.S. and the U.K., reports the Wall Street Journal, around two dozen stereotactic ablations are performed each year, but only in the most intractable cases of depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder and after extensive review by institutional review boards and intensive discussions with the patient, who must acknowledge the risks. Often, a different brain region is targeted, not the nucleus accumbens. Given the unpredictable and potentially harmful consequences of the procedure, experts are united in their condemnation of using the technique to treat addictions. “To lesion this region that is thought to be involved in all types of motivation and pleasure risks crippling a human being,” says Dr. Charles O’Brien, head of the Center for Studies of Addiction at the University of Pennsylvania.

David Linden, professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins and author of a recent book about the brain’s pleasure systems calls the surgery “horribly misguided.” He says “This treatment will almost certainly render the subjects unable to feel pleasure from a wide range of experiences, not just drugs of abuse.”

But some neurosurgeons see it differently. Dr. John Adler, professor emeritus of neurosurgery at Stanford University, collaborated with the Chinese researchers on the publication and is listed as a co-author. While he does not advocate the surgery and did not perform it, he believes it can provide valuable information about how the nucleus accumbens works, and how best to attempt to manipulate it. “I do think it’s worth learning from,” he says. ” As far as I’m concerned, ablation of the nucleus accumbens makes no sense for anyone. There’s a very high complication rate. [But] reporting it doesn’t mean endorsing it. While we should have legitimate ethical concerns about anything like this, it is a bigger travesty to put our heads in the sand and not be willing to publish it,” he says.

(MORE: Anesthesia Study Opens Window Into Consciousness)

Dr. Casey Halpern, a neurosurgery resident at the University of Pennsylvania makes a similar case. He notes that German surgeons have performed experimental surgery involving placing electrodes in the same region to treat the extreme lack of pleasure and motivation associated with otherwise intractable depression. “That had a 60% success rate, much better than [drugs like Prozac],” he says. Along with colleagues from the University of Magdeburg in Germany, Halpern has just published a paper in the Proceedings of the New York Academy of Sciences calling for careful experimental use of DBS in the nucleus accumbens to treat addictions, which have failed repeatedly to respond to other approaches. The paper cites the Chinese surgery data and notes that addiction itself carries a high mortality risk.

DBS, however, is quite different from ablation. Although it involves the risk of any brain surgery, the stimulation itself can be turned off if there are negative side effects, while surgical destruction of brain tissue is irreversible. That permanence—along with several other major concerns — has ethicists and addiction researchers calling for a stop to the ablation surgeries, and for journals to refuse to publish related studies.

Harriet Washington, author of Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, argues that by publishing the results of unethical studies, scientists are condoning the questionable conditions under which the trials are conducted. “When medical journals publish research that violates the profession’sethical guidelines, this serves not only to sanction such abuses, but to encourage them,” she says. “In doing so, this practice encourages a relaxing of moral standards that threatens all patients and subjects, but especially the medically vulnerable.”

(MORE: Real-Time Video: First Look at a Brain Losing Consciousness Under Anesthesia)

Shi-Min Fang, a Chinese biochemist who became a freelance journalist and recently won the journal Nature‘s Maddox prize for his exposes of widespread fraud in Chinese research, has revealed some of the subpar scientific practices behind research conducted in China, facing death threats and, as the New York Times reported, a beating with a hammer. He agrees that publishing such research only perpetuates the unethical practices. Asked by TIME to comment on the addiction surgery studies, Fang writes that publishing the research, particularly in western journals, “would encourage further unethical research, particularly in China where rewards for publication in international journals are high.”

While he doesn’t have the expertise to comment specifically on the ablation data, he says “the results of clinical research in China are very often fabricated. I suspect that the approvals by Ethics Committee mentioned in these papers were made up to meet publication requirement. I also doubt if the patients were really informed in detail about the nature of the study.” Fang also notes that two of the co-authors of the paper are advertising on the internet in Chinese, offering the surgery at a cost of 35,000 renminbi, about $5,600. That’s more than the average annual income in China, which is about $5,000.

Given the available evidence, in fact, it’s hard to find a scientific justification for even studying the technique in people at all. Carl Hart, associate professor of psychology at Columbia University and author of the leading college textbook on psychoactive drugs, says animal studies suggest the approach may ultimately fail as an effective treatment for addiction; a 1984 experiment, for example, showed that destroying the nucleus accumbens in rats does not permanently stop them from taking opioids like heroin and later research found that it similarly doesn’t work for curbing cocaine cravings. Those results alone should discourage further work in humans. “These data are clear,” he says, “If you are going to take this drastic step, you damn well better know all of the animal literature.” [Disclosure: Hart and I have worked on a book project together].

(MORE: Top 10 Medical Breakthroughs of 2012)

Moreover, in China, where addiction is so demonized that execution has been seen as an appropriate punishment and where the most effective known treatment for heroin addiction— methadone or buprenorphine maintenance— is illegal, it’s highly unlikely that addicted people could give genuinely informed consent for any brain surgery, let alone one that risks losing the ability to feel pleasure. And even if all of the relevant research suggested that ablating the nucleus accumbens prevented animals from seeking drugs, it would be hard to tell from rats or even primates whether the change was due to an overall reduction in motivation and pleasure or to a beneficial reduction in desiring just the drug itself.

There is no question that addiction can be difficult to treat, and in the most severe cases, where patients have suffered decades of relapses and failed all available treatments multiple times, it may make sense to consider treatments that carry significant risks, just as such dangers are accepted in fighting suicidal depression or cancer. But in the ablation surgery studies, some of the participants were reportedly as young as 19 years old and had only been addicted for three years. Addiction research strongly suggests that such patients are likely to recover even without treatment, making the risk-benefit ratio clearly unacceptable.

The controversy highlights the tension between the push for innovation and the reality of risk. Rules on informed consent didn’t arise from fears about theoretical abuses: they were a response to the real scientific horrors of the Holocaust. And ethical considerations become especially important when treating a condition like addiction, which is still seen by many not as an illness but as a moral problem to be solved by punishment. Scientific innovation is the goal, but at what price?

Read more: http://healthland.time.com/2012/12/13/controversial-surgery-for-addiction-burns-away-brains-pleasure-center/#ixzz2ExzobWQq

Thanks to Dr. Lutter for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.