Our brain’s ability to process information and adapt effectively is dependent on a number of factors, including genes, nutrition, and life experiences. These life experiences wield particular influence over the brain during a few sensitive periods when our most important muscle is most likely to undergo physical, chemical, and functional remodeling.

According to Tara Swart, a neuroscientist and senior lecturer at MIT, your “terrible twos” and those turbulent teen years are when the brain’s wiring is most malleable. As a result, traumatic experiences that occur during these time periods can alter brain activity and ultimately change gene expressions—sometimes for good.

Throughout the first two years of life, the brain develops at a rapid pace. However, around the second year, something important happens—babies begin to speak.

“We start to understand speech first, then we start to articulate speech ourselves and that’s a really complex thing that goes on in the brain,” Swart, who conducts ongoing research on the brain and how it affects how we become leaders, told Quartz. “Additionally, children start to walk—so from a physical point of view, that’s also a huge achievement for the brain.

Learning and understanding a new language forces your brain to work in new ways, connecting neurons and forming new pathways. This is a mentally taxing process, which is why learning a new language or musical instrument often feels exhausting.

With so many important changes happening to the brain in such a short period of time, physical or emotional trauma can cause potentially momentous interruptions to neurological development. Even though you won’t have any memories of the interruptions (most people can’t remember much before age five), any kind of traumatic event—whether it’s abuse, neglect, ill health, or separation from your loved ones—can lead to lasting behavioral and cognitive deficits later in life, warns Swart.

To make her point, Swart points to numerous studies on orphans in Romania during the 1980s and 1990s. After the nation’s communist regime collapsed, an economic decline swept throughout the region and 100,000 children found themselves in harsh, overcrowded government institutions.

“[The children] were perfectly well fed, clothed, washed, but for several reasons—one being that people didn’t want to spread germs—they were never cuddled or played with,” explains Swart. “There was a lot of evidence that these children grew up with some mental health problems and difficulty holding down jobs and staying in relationships.”

Swart continues: “When brain scanning became possible, they scanned the brains of these children who had grown up into adults and showed that they had issues in the limbic system, the part of the brain [that controls basic emotions].”

In short, your ability to maintain proper social skills and develop a sense of empathy is largely dependent on the physical affection, eye contact, and playtime of those early years. Even something as simple as observing facial expressions and understanding what those expressions mean is tied to your wellbeing as a toddler.

The research also found that the brains of the Romanian orphans had lower observable brain activity and were physically smaller than average. As a result, researchers concluded that children adopted into loving homes by age two have a much better chance of recovering from severe emotional trauma or disturbances.

The teenage years

By the time you hit your teenage years, the brain has typically reached its adult weight of about three pounds. Around this same time, the brain is starting to eliminate, or “prune” fragile connections and unused neural pathways. The process is similar to how one would prune a garden—cutting back the deadwood allows other plants to thrive.

During this period, the brain’s frontal lobes, especially the prefrontal cortex, experience increased activity and, for the first time, the brain is capable of comparing and analyzing several complex concepts at once. Similar to a baby learning how to speak, this period in an adolescent’s life is marked by a need for increasingly advanced communication skills and emotional maturity.

“At that age, they’re starting to become more understanding of social relationships and politics. It’s really sophisticated,” Swart noted. All of this brain activity is also a major reason why teenagers need so much sleep.

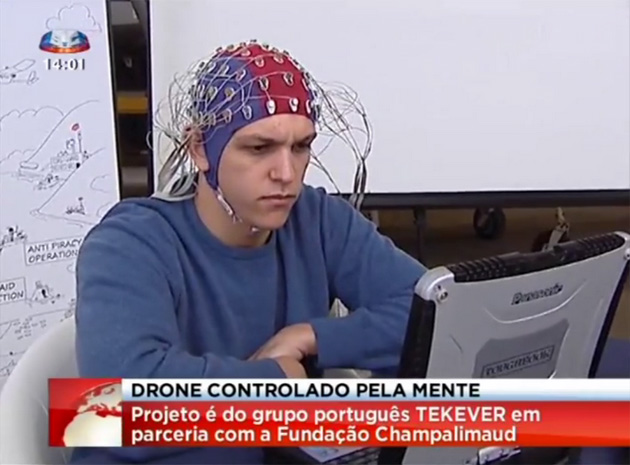

Swart’s research dovetails with the efforts of many other scientists who have spent decades attempting to understand how the brain develops, and when. The advent of MRIs and other brain-scanning technology has helped speed along this research, but scientists are still working to figure out what exactly the different parts of the brain do.

What is becoming more certain, however, is the importance of stability and safety in human development, and that such stability is tied to cognitive function. At any point in time, a single major interruption has the ability to throw off the intricate workings of our brain. We may not really understand how these events affect our lives until much later.

http://qz.com/470751/your-brain-is-particularly-vulnerable-to-trauma-at-two-distinct-ages/