Erika Check Hayden

Nature Medicine 20,1362–1364(2014)doi:10.1038/nm1214-1362Published online 04 December 2014

In 1889, the pioneering endocrinologist Charles Edouard Brown-Séquard told Parisian doctors that he had reinvigorated himself by injecting an extract made from dog and guinea pig testicles. Thousands of physicians began administering the extract—sold as “Elixir of Life”—to their patients. Though other researchers looked derisively on his salesmanship, his was among the early investigations that led to the eventual discovery of hormones.

The quest to end aging, rife with bizarre and doomed therapies, is perhaps as old as humanity itself. And even though researchers today have more sophisticated tools for studying aging, the hunt for drugs to prevent human decay has still seen many false leads.

Now, the field hopes to improve its track record with the entrance of two new players, Calico, which launched in September 2013, and Human Longevity, which entered the stage six months later. South San Francisco–based Calico, founded by Google with an initial commitment of at least $250 million, boasts an all-star slate of biotechnology industry leaders such as Genentech alums Art Levinson and Hal Barron and aging researchers David Botstein and Cynthia Kenyon. Human Longevity was founded by genome pioneer Craig Venter and hopes to use a big data approach to combat age-related disease.

The involvement of high-profile names from outside the aging field—and the deep pockets of a funder like Google—have inspired optimism among longevity researchers. “For Google to say, ‘This is something I’m putting a lot of money into,’ is a boost for the field,” says Stephanie Lederman, executive director of the New York–based American Federation for Aging Research, which funds aging research. “There’s a tremendous amount of excitement.”

The lift was badly needed; in August 2013, a major funder of antiaging research, the Maryland-based Ellison Medical Foundation, founded by billionaire Larry Ellison, had said it would no longer sponsor aging research. But so far, neither Calico nor Human Longevity has progressed enough to know whether they will be able to turn around the field’s losing track record, and the obstacles they face are formidable, say veterans of antiaging research.

“We’ve made inroads over the past 20 years or so,” says molecular biologist Leonard Guarente of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, who has founded and advised high-profile companies in the space. “But I think there’s a long way to go.”

Pathway to success?

Calico appears to be taking the approach that worked for Barron and Levinson at Genentech, the pioneering biotechnology company that has become among the more successful drug companies in the world by making targeted medicines—largely engineered proteins—that disrupt disease pathways in diseases such as cancer. The hallmark of Genentech’s approach has been to dissect the pathways involved in disease and then target them with biotechnology drugs. This past September, Calico announced an alliance with AbbVie, the drug development firm spun out of Abbott Laboratories in 2013. In that deal, Calico and AbbVie said they would jointly spend up to $1.5 billion to develop drugs for age-related diseases including neurodegenerative disorders and cancer.

Such an approach is representative of one way to cure aging: targeting the diseases that become more prevalent as people grow older. This follows the argument that treating such diseases is itself treating aging. The opposing view is to see aging as an inherently pathological program that, if switched off or reprogrammed, could be halted. But because regulators don’t consider the progression of life itself a disease, the semantic debate is moot to drug companies: they can only get drugs approved by targeting diseases that become more common with age, such as cancer, diabetes and neurodegenerative disorders.

Calico has a close view on disease targets. In another September announcement, the company revealed one of its first development areas: drugs related to a class of compounds called P7C3s, which appear to protect nerve cells in the brain from dying by activating an enzyme called nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase that inhibits cell death. The P7C3 compounds, discovered in 2010 by researchers at University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas, have been tested in numerous models of neurodegenerative diseases associated with aging, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease.

The AbbVie and P7C3 deals signal that Calico may focus on a traditional drug development strategy aimed at developing drugs that affect molecular players in the aging process in animal models. That approach makes sense to many who have been in the field for a long time, who say there is still much to learn about the molecular biology of aging: “The way Calico has said they are approaching this is the right way, which is to understand some fundamental aspects of the aging process and see how intervening in them affects that process,” says George Vlasuk, the chief executive of Cambridge, Massachusetts–based Navitor Pharmaceuticals and former head of the now defunct antiaging company Sirtris Pharmaceuticals.

But so far that approach has been difficult to translate successfully into interventions that delay aging or prevent age-related disease. For the most part, the biology of aging has been worked out in animal models; Kenyon’s foundational discoveries, for instance, were made in Caenorhabditis elegans roundworms. But the legion of companies that have failed to commercialize these discoveries is large, and some in the field now think that further progress can be made only by studying human aging. Screening for drugs that affect lifespan in model organisms such as yeast and nematodes is a gamble, says physician Nir Barzilai of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, who leads a large study of human centenarians. “I’m not sure those are going to be so important.”

Human focus

Craig Venter is squarely in the camp of those who believe the focus must shift towards humans. His Human Longevity is taking a big data dive into human aging, planning to sequence the genes of up to 100,000 people per year and analyze a slew of phenotypic data about them, including their protein profiles, the microbial content of their bodies and digitized imagery of their bodies. “We’re trying to get as much information as we can about humans so that we can find the components in the human genome that are predictive of those features,” Venter told Nature Medicine. “The model organism approach has largely failed. There’s only one model for humans, and that’s humans.”

Venter has a point, according to Judith Campisi, a cell and molecular biologist at the Buck Institute for Age Research in Novato, California. “We now have lots of targets, so I think there’s room for optimism,” she says. “But we’re still swimming in a sea of ignorance about how all these pathways and targets are integrated and how we can intervene in them safely.”

Michael West, CEO of the California-based regenerative medicine company BioTime, knows this well. In 1990, West founded a company, Geron, with $40 million from Silicon Valley venture capitalists such as Menlo Park, California–based Kleiner Perkins, dedicated to activating an enzyme called telomerase to forestall human aging. Telomerase activity, discovered in 1984, extends telomeres—the ends of chromosomes, thought to function as timekeepers of the age of a cell. But researchers soon found that human cancer cells have overactive telomerase, and it’s now thought that telomerase serves a highly useful function as a defense against unchecked cell growth that could lead to cancer1. Geron has shifted its telomerase strategy to blocking telomerase to fight cancer; it no longer works on longevity. “The focus on aging was abandoned,” West says.

Other companies, however, carried forward with the search for drugs against aging, inspired by a 1982 finding that mutating some genes in roundworms could enable them to live longer2. For example, one mutant lived for an average of 40% to 60% longer than normal, and at warm temperatures more than doubled its maximum life expectancy from 22 to 46.2 days. It was the first demonstration that aging was not an inevitable process. The work triggered a flurry of activity to find genes linked to aging and use them in interventions to stave off age-related disease.

Companies rooted in this strategy include Elixir Pharmaceuticals, cofounded in 1999 by Guarente and Kenyon, and Sirtris, established in 2004 by one of Guarente’s former students, David Sinclair. Kenyon had discovered genes in nematodes that extended life; with Guarente, she hoped to make drugs that could do this in humans. Guarente and Sinclair founded different companies, but both were interested in a pathway discovered at MIT that, they believed, acted similarly to a drastic treatment, called calorie restriction, long known to extend the lives of rats. If the rats were fed 40% fewer calories than normal, they could live up to 20–40% longer than the average rat. Guarente’s lab discovered that boosting the dose of genes called sirtuins could prolong the lives of roundworms3, and Sinclair published similar evidence in yeast. They thought that sirtuins worked through the same pathway as calorie restriction and that this same pathway was targeted by a naturally occurring compound called resveratrol found in red grapes and red wine. Both companies began looking for chemicals similar to resveratrol that, they predicted, might ultimately cure aging.

Sirtuin stepbacks

UK-based GlaxoSmithKline bought Sirtris for $720 million in 2008, a move seen as an important endorsement of that “calorie restriction mimetic” strategy. But other researchers were not able to reproduce some of Sinclair’s key studies4—for instance, those showing that resveratrol exerted its antiaging effects through sirtuins. It was also later found that the kind of diet fed to lab mice could affect whether or not sirtuins extended their lifespans; those eating a very high-fat diet seemed to benefit5, but it wasn’t clear that this was the most relevant model for human beings. Similar arguments about diet composition have yielded conflicting results for calorie restriction studies in monkeys and have raised the question of whether animal models of caloric restriction that appear to find a benefit are really just proving that bringing fat animals down to normal weight helps keep them disease free, thus extending lifespan.

Last year, GSK closed Sirtris, absorbed its drug development work and laid off some of Sirtris’s 60 employees. Elixir shut down some time after 2010, having burned through $82 million in venture capital.

The Sirtris experience underscored the unpredictability of aging research. Since the field does not agree on biological readouts of aging, such as altered signaling of certain pathways or expression of particular molecules that serve as proximate measurements of the aging process, the only way to do these studies was to follow animals until they died in order to record their lifespan.

The US National Institute on Aging stepped in, organizing a 1999 meeting that led to the Interventions Testing Program, aimed at bringing some order to the field. The program would systematically run experiments of candidate life extension treatments in mice at three separate sites. The hope was that the studies, which began in 2004, would help identify candidate life extension interventions that most deserved to be taken forward.

Already, most researchers agree, the program has succeeded in building more consensus around some drugs. One of the winners from the program so far, for instance, has been rapamycin, a relatively old drug given to kidney transplant recipients and some patients with cancer. In 2009, the drug was shown to extend the lives of genetically diverse mice7. (Resveratrol failed to prolong mouse lifespan in these same studies.) It was also shown to work in much older mice—the equivalent of about 60-year-old people—than had been studied in previous experiments, a situation that researchers say is much more relevant to the way antiaging drugs would be used in human patients. “You’re not going to give these drugs to teenagers,” says Matthew Kaeberlein of the University of Washington in Seattle. “You’ll probably want to give them to people who are certainly post-reproductive, and perhaps in their 60s and 70s.”

Strong signals

Rapamycin suffers from some of the same issues as previous failed antiaging treatments. It’s an old, unpatentable drug, like resveratrol, and has side effects such as a diabetes-like syndrome when given to transplant patients, who continue to take the drug for life after their surgeries. The side effects are worrying for a potential medicine that might be given over years to delay aging. But the signal from the rapamycin studies in mice is so strong that it’s now seen as one of the most promising leads in aging research, even despite these problems. Navitor, for instance, is looking for compounds that influence the mTOR, short for the ‘mammalian target of rapamycin’, pathway, through which rapamycin seems to extend lifespan. The pathway has the potential to influence a wide range of diseases, including neurodegenerative, autoimmune, metabolic and rare diseases and cancer. That’s been enough to entice investors to fund a $23.5 million financing in the company in June. By targeting a specific branch of the mTOR pathway, Navitor hopes they can elicit the benefits of rapamycin without its side effects.

Vlasuk says that companies like his now focus on treating age-related diseases rather than trumpeting the potential to cure aging itself and all associated maladies. “I’m acutely aware that I don’t want to be caught up in the same hype cycle that Sirtris was at one time,” Vlasuk says.

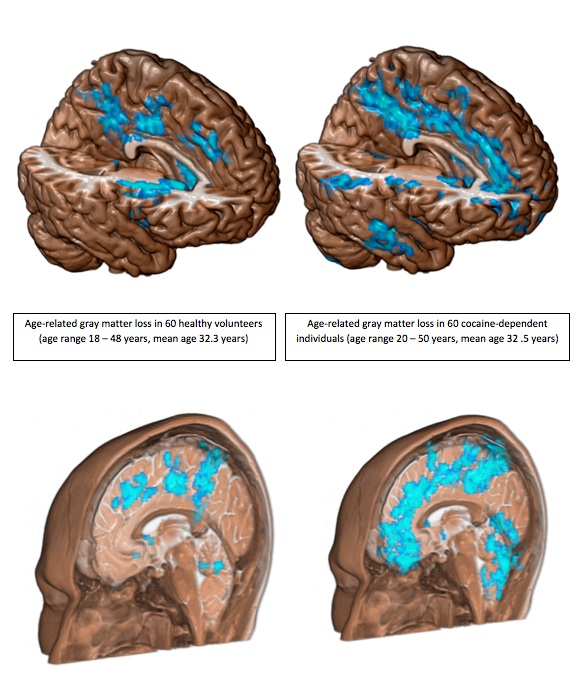

The field is also maturing in other ways. For instance, there’s a growing realization that the people who wish to take life extension drugs will be more old than young, but that it might be difficult to reverse age-related pathology once it has already set in.

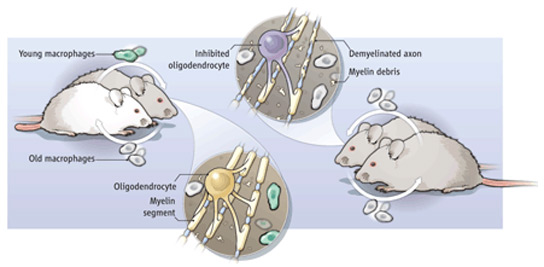

Meanwhile, young researchers are taking the field in new directions. In May, three groups published results of experiments in which they transferred blood or blood products from young to old mice. They showed that the technique can rejuvenate muscle, neurons and age-related cognitive decline. A batch of companies is now forming to translate the finding into people; one, privately funded Alkahest, has begun enrolling patients into a study that will test whether blood donated from young adults and infused into patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease can improve their symptoms. Importantly, says regenerative biologist Amy Wagers of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, one of the pioneers of this approach, it seems to reverse some signs of age-related disease: “This notion that you can do some good even after pathology begins means its much more likely that we can come to a place where we can support people with more healthy aging,” she says.

The challenge of clinical trials for aging-related illnesses is familiar to the brains behind the newest antiaging companies. One solution could be to prove that an intervention prevents the sick from becoming sicker. It’s long been suspected, for instance, that the diabetes drug metformin has antiaging properties, but it can have potential side effects because it inhibits glucose production by the liver, so it can’t be given to healthy people. This year, however, UK-based researchers reported in a large retrospective trial that patients with diabetes taking metformin lived a small but significantly longer time than both diabetics taking another class of drugs and healthy people who were not taking metformin.

Barzilai has been impressed enough by these and other findings to try to round up funding for an international clinical trial to test whether metformin or some other drug improves health of the elderly by delaying the onset of a second disease in those who begin taking it when they are newly diagnosed with diabetes. He argues that second diseases, which can include cancer, become much more likely once a patient has been diagnosed with a first. Preventing the onset of a second disease is a way of extending longevity, he argues, by reducing the disease burden in any one patient. “Let’s show that we can delay aging and delay the onset of a second disease,” he says. “If we can do that, we can make FDA [the US Food and Drug Administration] change its review process and look at better potential drugs that delay aging.”

The challenges of testing treatments in patients with age-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, are formidable. Hal Barron knows this well; he presided over a failed Genentech trial of an antibody called crenezumab, which was designed to alleviate symptoms of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Still, that hasn’t deterred him or Levinson from going all in on neurodegenerative diseases with Calico.

“Art Levinson is one of the smartest guys around in terms of his perception of what drug discovery can do,” Vlasuk says. “His involvement in Calico and the group that he’s assembling there and the backing that Google has provided for this has really opened a lot of people’s eyes.” The question now is what Levinson, Venter and others are seeing—and whether it will be enough to lead aging research to finally fulfill its potential.