By Jerry Adler

SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE

Telepathy, 2015: At the Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering of the University of Washington, a young woman dons an electroencephalogram cap, studded with electrodes that can read the minute fluctuations of voltage across her brain. She is playing a game, answering questions by turning her gaze to one of two strobe lights labeled “yes” and “no.” The “yes” light is flashing at 13 times a second, the “no” at 12, and the difference is too small for her to perceive, but sufficient for a computer to detect in the firing of neurons in her visual cortex. If the computer determines she is looking at the “yes” light, it sends a signal to a room in another building, where another woman is sitting with a magnetic coil positioned behind her head. A “yes” signal activates the magnet, causing a brief disturbance in the second subject’s visual field, a virtual flash (a “phosphene”) that she describes as akin to the appearance of heat lightning on the horizon. In this way, the first woman’s answers are conveyed to another person across the campus, going “Star Trek” one better: exchanging information between two minds that aren’t even in the same place.

For nearly all of human history, only the five natural senses were known to serve as a way into the brain, and language and gesture as the channels out. Now researchers are breaching those boundaries of the mind, moving information in and out and across space and time, manipulating it and potentially enhancing it. This experiment and others have been a “demonstration to get the conversation started,” says researcher Rajesh Rao, who conducted it along with his colleague Andrea Stocco. The conversation, which will likely dominate neuroscience for much of this century, holds the promise of new technology that will dramatically affect how we treat dementia, stroke and spinal cord injuries. But it will also be about the ethics of powerful new tools to enhance thinking, and, ultimately, the very nature of consciousness and identity.

That new study grew out of Rao’s work in “brain-computer interfaces,” which process neural impulses into signals that can control external devices. Using an EEG to control a robot that can navigate a room and pick up objects—which Rao and his colleagues demonstrated as far back as 2008—may be commonplace someday for quadriplegics.

In what Rao says was the first instance of a message sent directly from one human brain to another, he enlisted Stocco to help play a basic “Space Invaders”-type game. As one person watched the attack on a screen and communicated by using only thought the best moment to fire, the other got a magnetic impulse that caused his hand, without conscious effort, to press a button on a keyboard. After some practice, Rao says, they got quite good at it.

“That’s nice,” I said, when he described the procedure to me. “Can you get him to play the piano?”

Rao sighed. “Not with anything we’re using now.”

For all that science has studied and mapped the brain in recent decades, the mind remains a black box. A famous 1974 essay by the philosopher Thomas Nagel asked, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” and concluded that we will never know; another consciousness—another person’s, let alone a member of another species—can never be comprehended or accessed. For Rao and a few others to open that door a tiny crack, then, is a notable achievement, even if the work has mostly underscored how big a challenge it is, both conceptually and technologically.

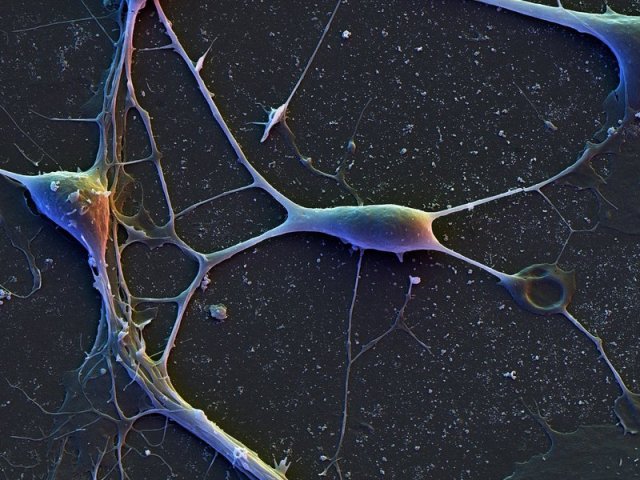

The computing power and the programming are up to the challenge; the problem is the interface between brain and computer, and especially the one that goes in the direction from computer to brain. How do you deliver a signal to the right group of nerve cells among the estimated 86 billion in a human brain? The most efficient approach is an implanted transceiver that can be hard-wired to stimulate small regions of the brain, even down to a single neuron. Such devices are already in use for “deep brain stimulation,” a technique for treating patients with Parkinson’s and other disorders with electrical impulses. But it’s one thing to perform brain surgery for an incurable disease, and something else to do it as part of an experiment whose benefits are speculative at best.

So Rao used a technique that does not involve opening the skull, a fluctuating magnetic field to induce a tiny electric current in a region of the brain. It appears to be safe—his first volunteer was his collaborator, Stocco—but it is a crude mechanism. The smallest area that can be stimulated in this way, Rao says, is not quite half an inch across. This limits its application to gross motor movements, such as hitting a button, or simple yes-or-no communication.

Another way to transmit information, called focused ultrasound, appears to be capable of stimulating a region of the brain as small as a grain of rice. While the medical applications for ultrasound, such as imaging and tissue ablation, use high frequencies, from 800 kilohertz up to the megahertz range, a team led by Harvard radiologist Seung-Schik Yoo found that a frequency of 350 kilohertz works well, and apparently safely, to send a signal to the brain of a rat. The signal originated with a human volunteer outfitted with an EEG, which sampled his brainwaves; when he focused on a specific pattern of lights on a computer screen, a computer sent an ultrasound signal to the rat, which moved his tail in response. Yoo says the rat showed no ill effects, but the safety of focused ultrasound on the human brain is unproven. Part of the problem is that, unlike magnetic stimulation, the mechanism by which ultrasound waves—a form of mechanical energy—creates an electric potential isn’t fully understood. One possibility is that it operates indirectly by “popping” open the vesicles, or sacs, within the cells of the brain, flooding them with neurotransmitters, like delivering a shot of dopamine to exactly the right area. Alternatively, the ultrasound could induce cavitation—bubbling—in the cell membrane, changing its electrical properties. Yoo suspects that the brain contains receptors for mechanical stimulation, including ultrasound, which have been largely overlooked by neuroscientists. Such receptors would account for the phenomenon of “seeing stars,” or flashes of light, from a blow to the head, for instance. If focused ultrasound is proven safe, and becomes a feasible approach to a computer-brain interface, it would open up a wide range of unexplored—in fact, barely imagined—possibilities.

Direct verbal communication between individuals—a more sophisticated version of Rao’s experiment, with two connected people exchanging explicit statements just by thinking them—is the most obvious application, but it’s not clear that a species possessing language needs a more technologically advanced way to say “I’m running late,” or even “I love you.” John Trimper, an Emory University doctoral candidate in psychology, who has written about the ethical implications of brain-to-brain interfaces, speculates that the technology, “especially through wireless transmissions, could eventually allow soldiers or police—or criminals—to communicate silently and covertly during operations.” That would be in the distant future. So far, the most content-rich message sent brain-to-brain between humans traveled from a subject in India to one in Strasbourg, France. The first message, laboriously encoded and decoded into binary symbols by a Barcelona-based group, was “hola.” With a more sophisticated interface one can imagine, say, a paralyzed stroke victim communicating to a caregiver—or his dog. Still, if what he’s saying is, “Bring me the newspaper,” there are, or will be soon, speech synthesizers—and robots—that can do that. But what if the person is Stephen Hawking, the great physicist afflicted by ALS, who communicates by using a cheek muscle to type the first letters of a word? The world could surely benefit from a direct channel to his mind.

Maybe we’re still thinking too small. Maybe an analog to natural language isn’t the killer app for a brain-to-brain interface. Instead, it must be something more global, more ambitious—information, skills, even raw sensory input. What if medical students could download a technique directly from the brain of the world’s best surgeon, or if musicians could directly access the memory of a great pianist? “Is there only one way of learning a skill?” Rao muses. “Can there be a shortcut, and is that cheating?” It doesn’t even have to involve another human brain on the other end. It could be an animal—what would it be like to experience the world through smell, like a dog—or by echolocation, like a bat? Or it could be a search engine. “It’s cheating on an exam if you use your smartphone to look things up on the Internet,” Rao says, “but what if you’re already connected to the Internet through your brain? Increasingly the measure of success in society is how quickly we access, digest and use the information that’s out there, not how much you can cram into your own memory. Now we do it with our fingers. But is there anything inherently wrong about doing it just by thinking?”

Or, it could be your own brain, uploaded at some providential moment and digitally preserved for future access. “Let’s say years later you have a stroke,” says Stocco, whose own mother had a stroke in her 50s and never walked again. “Now, you go to rehab and it’s like learning to walk all over again. Suppose you could just download that ability into your brain. It wouldn’t work perfectly, most likely, but it would be a big head start on regaining that ability.”

Miguel Nicolelis, a creative Duke neuroscientist and a mesmerizing lecturer on the TED Talks circuit, knows the value of a good demonstration. For the 2014 World Cup, Nicolelis—a Brazilian-born soccer aficionado—worked with others to build a robotic exoskeleton controlled by EEG impulses, enabling a young paraplegic man to deliver the ceremonial first kick. Much of his work now is on brain-to-brain communication, especially in the highly esoteric techniques of linking minds to work together on a problem. The minds aren’t human ones, so he can use electrode implants, with all the advantages that conveys.

One of his most striking experiments involved a pair of lab rats, learning together and moving in synchrony as they communicated via brain signals. The rats were trained in an enclosure with two levers and a light above each. The left- or right-hand light would flash, and the rats learned to press the corresponding lever to receive a reward. Then they were separated, and each fitted with electrodes to the motor cortex, connected via computers that sampled brain impulses from one rat (the “encoder”), and sent a signal to a second (the “decoder”). The “encoder” rat would see one light flash—say, the left one—and push the left-hand lever for his reward; in the other box, both lights would flash, so the “decoder” wouldn’t know which lever to push—but on receiving a signal from the first rat, he would go to the left as well.

Nicolelis added a clever twist to this demonstration. When the decoder rat made the correct choice, he was rewarded, and the encoder got a second reward as well. This served to reinforce and strengthen the (unconscious) neural processes that were being sampled in his brain. As a result, both rats became more accurate and faster in their responses—“a pair of interconnected brains…transferring information and collaborating in real time.” In another study, he wired up three monkeys to control a virtual arm; each could move it in one dimension, and as they watched a screen they learned to work together to manipulate it to the correct location. He says he can imagine using this technology to help a stroke victim regain certain abilities by networking his brain with that of a healthy volunteer, gradually adjusting the proportions of input until the patient’s brain is doing all the work. And he believes this principle could be extended indefinitely, to enlist millions of brains to work together in a “biological computer” that tackled questions that could not be posed, or answered, in binary form. You could ask this network of brains for the meaning of life—you might not get a good answer, but unlike a digital computer, “it” would at least understand the question. At the same time, Nicolelis criticizes efforts to emulate the mind in a digital computer, no matter how powerful, saying they’re “bogus, and a waste of billions of dollars.” The brain works by different principles, modeling the world by analogy. To convey this, he proposes a new concept he calls “Gödelian information,” after the mathematician Kurt Gödel; it’s an analog representation of reality that cannot be reduced to bytes, and can never be captured by a map of the connections between neurons (“Upload Your Mind,” see below). “A computer doesn’t generate knowledge, doesn’t perform introspection,” he says. “The content of a rat, monkey or human brain is much richer than we could ever simulate by binary processes.”

The cutting edge of this research involves actual brain prostheses. At the University of Southern California, Theodore Berger is developing a microchip-based prosthesis for the hippocampus, the part of the mammalian brain that processes short-term impressions into long-term memories. He taps into the neurons on the input side, runs the signal through a program that mimics the transformations the hippocampus normally performs, and sends it back into the brain. Others have used Berger’s technique to send the memory of a learned behavior from one rat to another; the second rat then learned the task in much less time than usual. To be sure, this work has only been done in rats, but because degeneration of the hippocampus is one of the hallmarks of dementia in human beings, the potential of this research is said to be enormous.

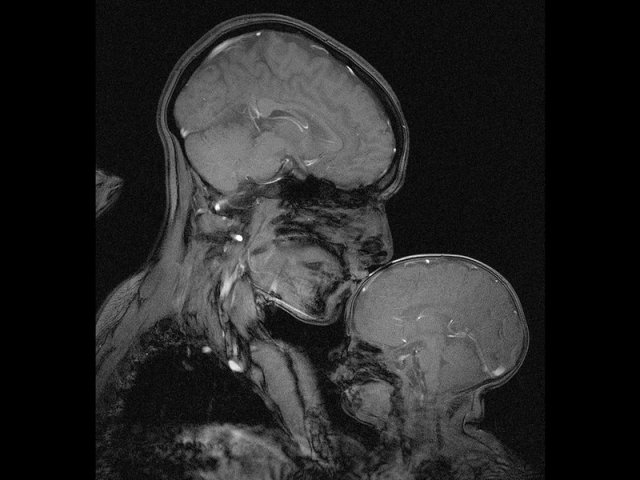

Given the sweeping claims for the future potential of brain-to-brain communication, it’s useful to list some of the things that are not being claimed. There is, first, no implication that humans possess any form of natural (or supernatural) telepathy; the voltages flickering inside your skull just aren’t strong enough to be read by another brain without electronic enhancement. Nor can signals (with any technology we possess, or envision) be transmitted or received surreptitiously, or at a distance. The workings of your mind are secure, unless you give someone else the key by submitting to an implant or an EEG. It is, however, not too soon to start considering the ethical implications of future developments, such as the ability to implant thoughts in other people or control their behavior (prisoners, for example) using devices designed for those purposes. “The technology is outpacing the ethical discourse at this time,” Emory’s Trimper says, “and that’s where things get dicey.” Consider that much of the brain traffic in these experiments—and certainly anything like Nicolelis’ vision of hundreds or thousands of brains working together—involves communicating over the Internet. If you’re worried now about someone hacking your credit card information, how would you feel about sending the contents of your mind into the cloud?There’s another track, though, on which brain-to-brain communication is being studied. Uri Hasson, a Princeton neuroscientist, uses functional magnetic resonance imaging to research how one brain influences another, how they are coupled in an intricate dance of cues and feedback loops. He is focusing on a communication technique that he considers far superior to EEGs used with transcranial magnetic stimulation, is noninvasive and safe and requires no Internet connection. It is, of course, language.

Read more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/why-brain-brain-communication-no-longer-unthinkable-180954948/#y1xADWfAk1VkKIJc.99