Prof Sarah Tabrizi , from the UCL Institute of Neurology, led the trials

By James Gallagher

The defect that causes the neurodegenerative disease Huntington’s has been corrected in patients for the first time, the BBC has learned. An experimental drug, injected into spinal fluid, safely lowered levels of toxic proteins in the brain. The research team, at University College London, say there is now hope the deadly disease can be stopped.

Experts say it could be the biggest breakthrough in neurodegenerative diseases for 50 years.

Huntington’s is one of the most devastating diseases. Some patients described it as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and motor neurone disease rolled into one.

Peter Allen, 51, is in the early stages of Huntington’s and took part in the trial: “You end up in almost a vegetative state, it’s a horrible end.”

Huntington’s blights families. Peter has seen his mum Stephanie, uncle Keith and grandmother Olive die from it. Tests show his sister Sandy and brother Frank will develop the disease. The three siblings have eight children – all young adults, each of whom has a 50-50 chance of developing the disease.

The unstoppable death of brain cells in Huntington’s leaves patients in permanent decline, affecting their movement, behaviour, memory and ability to think clearly.

Peter, from Essex, told me: “It’s so difficult to have that degenerative thing in you.

“You know the last day was better than the next one’s going to be.”

Huntington’s generally affects people in their prime – in their 30s and 40s

Patients die around 10 to 20 years after symptoms start

About 8,500 people in the UK have Huntington’s and a further 25,000 will develop it when they are older

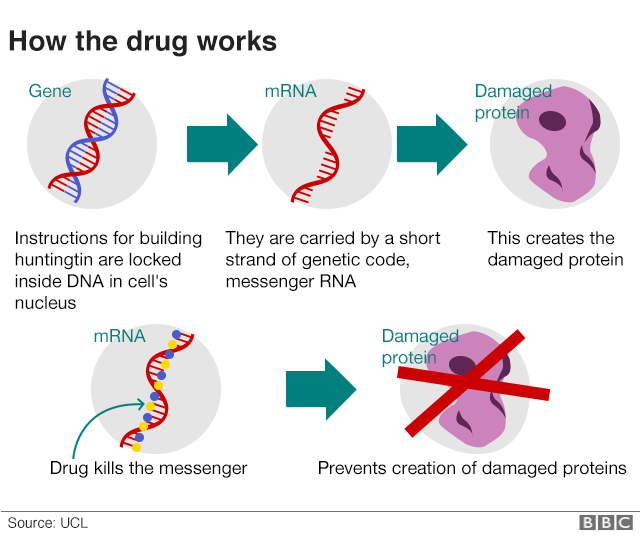

Huntington’s is caused by an error in a section of DNA called the huntingtin gene. Normally this contains the instructions for making a protein, called huntingtin, which is vital for brain development. But a genetic error corrupts the protein and turns it into a killer of brain cells.

The treatment is designed to silence the gene.

On the trial, 46 patients had the drug injected into the fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord. The procedure was carried out at the Leonard Wolfson Experimental Neurology Centre at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. Doctors did not know what would happen. One fear was the injections could have caused fatal meningitis. But the first in-human trial showed the drug was safe, well tolerated by patients and crucially reduced the levels of huntingtin in the brain.

Prof Sarah Tabrizi, the lead researcher and director of the Huntington’s Disease Centre at UCL, told the BBC: “I’ve been seeing patients in clinic for nearly 20 years, I’ve seen many of my patients over that time die. For the first time we have the potential, we have the hope, of a therapy that one day may slow or prevent Huntington’s disease . This is of groundbreaking importance for patients and families.”

Doctors are not calling this a cure. They still need vital long-term data to show whether lowering levels of huntingtin will change the course of the disease. The animal research suggests it would. Some motor function even recovered in those experiments.

Peter, Sandy and Frank – as well as their partners Annie, Dermot and Hayley – have always promised their children they will not need to worry about Huntington’s as there will be a treatment in time for them. Peter told the BBC: “I’m the luckiest person in the world to be sitting here on the verge of having that. “Hopefully that will be made available to everybody, to my brothers and sisters and fundamentally my children.”

He, along with the other trial participants, can continue taking the drug as part of the next wave of trials. They will set out to show whether the disease can be slowed, and ultimately prevented, by treating Huntington’s disease carriers before they develop any symptoms.

Prof John Hardy, who was awarded the Breakthrough Prize for his work on Alzheimer’s, told the BBC: “I really think this is, potentially, the biggest breakthrough in neurodegenerative disease in the past 50 years. That sounds like hyperbole – in a year I might be embarrassed by saying that – but that’s how I feel at the moment.”

The UCL scientist, who was not involved in the research, says the same approach might be possible in other neurodegenerative diseases that feature the build-up of toxic proteins in the brain. The protein synuclein is implicated in Parkinson’s while amyloid and tau seem to have a role in dementias.

Off the back of this research, trials are planned using gene-silencing to lower the levels of tau.

Prof Giovanna Mallucci, who discovered the first chemical to prevent the death of brain tissue in any neurodegenerative disease, said the trial was a “tremendous step forward” for patients and there was now “real room for optimism”.

But Prof Mallucci, who is the associate director of UK Dementia Research Institute at the University of Cambridge, cautioned it was still a big leap to expect gene-silencing to work in other neurodegenerative diseases.

She told the BBC: “The case for these is not as clear-cut as for Huntington’s disease, they are more complex and less well understood. But the principle that a gene, any gene affecting disease progression and susceptibility, can be safely modified in this way in humans is very exciting and builds momentum and confidence in pursuing these avenues for potential treatments.”

The full details of the trial will be presented to scientists and published next year.

The therapy was developed by Ionis Pharmaceuticals, which said the drug had “substantially exceeded” expectations, and the licence has now been sold to Roche.