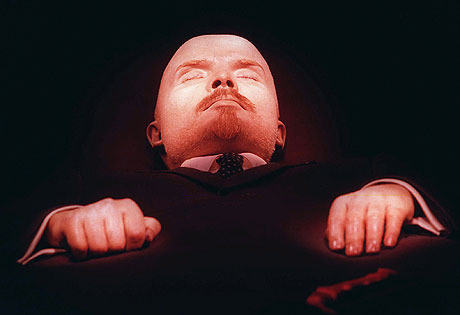

In a mass grave dating to the 1500s on the Venetian island of Lazzaretto Nuovo, this skull of a woman was found with a brick shoved in its mouth. Researchers think gravediggers came upon the skeleton and feared she was a vampire.

by Heather Whipps

The remains of a medieval “vampire” have been discovered among the corpses of 16th century plague victims in Venice, according to an Italian archaeologist who led the dig.

The body of the woman was found in a mass grave on the Venetian island of Lazzaretto Nuovo. Suspecting that she might be a vampire, a common folk belief at the time, gravediggers shoved a rock into her skull to prevent her from chewing through her shroud and infecting others with the plague, said anthropologist Matteo Borrini of the University of Florence.

In the absence of medical science, vampires were just one of many possible contemporary explanations for the spread of the Venetian plague in 1576, which ran rampant through the city and ultimately killed up to 50,000 people, some officials estimate.

Italy’s famous canal city wasn’t really overrun with medieval Draculas, however.

With hundreds of Venetians dying every day, gravediggers likely just misinterpreted the corpses they saw at varying levels of decomposition while reopening fresh mass graves, said Borrini.

The “stages which reduce the corpse to a skeleton were poorly known because they happen in the grave,” Borrini told LiveScience. “Graves were usually reopened after years, when the body had completely turned into a skeleton.”

Death exposed

Vampire superstition was already part of European culture by the time the bubonic plague reappeared on the continent in sporadic outbreaks throughout the late 1500s. The classic folkloric image of the undead, bloodsucking vampire likely originated in Eastern Europe and spread westwards, historians say, blending and morphing with local beliefs as it went.

Ignorance about the natural stages of decomposition probably fed the original vampire myths, Borrini said, noting that historical documentation of vampires harped on the oddly life-like appearance of recently buried bodies.

“There are some recurring aspects in vampire exhumation reports (usually written in the 17th and 18th century by church-goers and well-educated men, and sometimes even by scientists): uncorrupted corpse, pliable limbs, smooth and tensed skin, renewed beard and nails,” Borrini said. At the time “death was linked to a cold and stiff corpse, or to a blanched skeleton (dry bones),” he said, so evidence of anything to the contrary was considered worrisome when the rare body was exhumed for examination.

In the middle of the plague in Venice, however, victims were being dumped into mass graves such as the one on Lazzaretto Nuovo very regularly, exposing bodies at every gruesome stage of decay.

Frightened gravediggers

A phenomenon that occurs early on in the process of decomposition – abdominal bloating – is what likely concerned the Venetian gravediggers, Borrini said. When humans die, the body releases a myriad of bacterial gases that cause a corpse to bloat with fluid, usually just a few days after death in the absence of any kind of preservation or protection from coffins.

“During this phase, the decay of the gastrointestinal tract contents and lining create a dark fluid called ‘purge fluid’; it can flow freely from the nose and mouth…and it could easily be confused with the blood sucked by the vampire,” said Borrini.

If the “vampire” woman was emitting blood from her mouth, the fluid likely moistened her burial shroud causing it to sink into her jaw cavity and be dissolved by the fluids, Borrini said, making it appear as though she was trying to bite through her shroud. When discovered in that state, a stone was jammed into her mouth as a kind of exorcism to prevent her from potentially spreading the disease further, the researchers think.

Medieval skeletons have been found in a similar state in other parts of Europe, Borrini said.

Bad times = superstition

It is difficult to decipher whether the brick-in-mouth tactic discovered in Venice was truly based on a deep fear of vampires or was merely extra precaution in troubled times, Borrini acknowledged.

“From a forensic point of view, we can accept the reports about the ‘vampire corpses’ as real descriptions, but we can also realize why those legends spread especially during plagues,” Borrini said. The mere fact that tombs and mass graves were reopened so frequently during pandemics to bury new victims of a disease, exposing partially decomposed bodies, only increased “dread and superstition among people who were already suffering pestilence and massive death,” he said.

Borrini presented his findings to a recent meeting of the American Association of Forensic Sciences, along with forensic orthodontist Emilio Nuzzolese.