At this moment, there are 115,000 Americans who will die if they don’t get matched with a donated organ. Twenty of them die every day, according to data collected by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS).

Part of the reason that waiting list is so long is because (surprise) organs don’t fare too well without a warm, gooey body keeping them safe. Both a liver and pancreas, for which the UNOS says 14,000 and 900 people respectively are currently waiting, can only be transplanted within twelve hours of donation. Another 4,000 people are waiting for a new heart, but those only last six hours outside the body before they begin to decay.

The 95,000 people waiting on a kidney donation get a little bit more wiggle room — those can last about 30 hours. But considering all of the logistical hurdles and difficulties of matching, donating, transporting, and, transplanting organs, recipients need to be ready for surgery more or less immediately once one is available.

The simplest way to get more organs to the people who need them, it would seem, is to freeze donated organs until they’re needed, like you might do with a casserole.

It’s such a simple idea that scientists and doctors came up with the idea decades ago, but they encountered two major roadblocks that seemed insurmountable — at least, until very recently.

The doctors, cryobiologists, engineers, and physicists at biotech company Arigos Biomedical may have come up with a way to freeze and store organs for as long as necessary. The company, previously funded by two of Peter Thiel’s science-focused foundations, recently raised just under $1 million in a seed round (participants included a venture firm, an angel investor and a family foundation, they note). Arigos co-founder and CEO Tanya Jones tells Futurism that they hope to begin human experiments as soon as 2020; if that goes well the technique could be used in clinics five to seven years after that.

If their technology works, it could shorten or even eliminate some of the organ transplant waitlists in America and around the world.

To understand the science that makes this possible, we need to look at why cryopreservation hasn’t worked in the past.

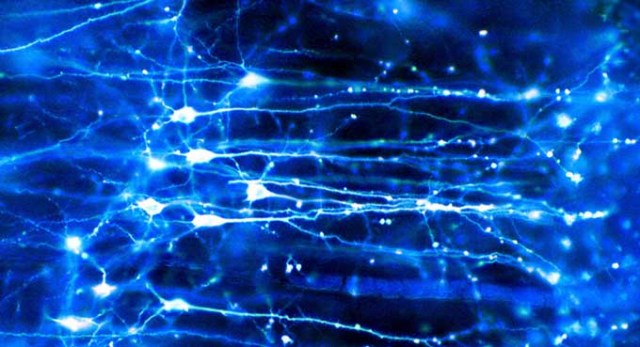

The first hurdle that cryobiologists need to overcome happens while the organ is on its way down to -120 degrees Celsius, the temperature at which molecular activity stops and organs can be stored indefinitely. People, you may recall, are mostly water, and when water freezes it expands into solid ice. This fact can cause problems as organs freeze, since congealing ice pulls water from nearby cells that need it and can rupture blood vessels as it expands. This is especially a problem since expansion and freezing happen at different times as organs freeze from the outside in.

The second hurdle comes during the warming process: just like an ice cube thrown into a glass of lukewarm water, organs tended to fracture and pop as they thawed. Not too helpful if you’re trying to replace a leaky lung or heart with a non-leaky one.

Scientists solved the first problem, Jones told Futurism, in the 1970s when they discovered a process called vitrification: pumping a cocktail of organic compounds into the organs pulled out most of the water. The remaining solution — water mixed with the added organic molecules — was so full of stuff that it didn’t form ice. Instead, it froze into a type of solid glass that didn’t damage the organs the way ice did. As a result, organs could be frozen without worrying about harmful ice buildup.

But many solutions used in vitrification ended up being toxic. And the second problem, the fracturing issue, still eluded scientists. Over the following decades, most lost hope and gave up.

Jones says that she and Arigos cofounder Stephen Van Sickle found a new solution when Van Sickle took a trip to the library and realized how many old research papers chronicled the attempts to prevent fracturing.

“He went to a library and uncovered a line of old research in the transplant world that was abandoned,” says Jones.

They found a way to flush out all the arteries and veins of the organ and replace it with gas. In the past, scientists had tried replacing the blood and liquid found in a donated heart with oxygen gas, which gave the organs a little bit of extra support and padding as they grew rigid. The field then shifted towards liquids. These liquid perfusions tended to work a little bit better but left the realm of gas cushions as an unexplored loose end.

Jones and Van Sickle decided gas was worth a shot — helium gas in particular, because it wouldn’t be toxic to the donated organs. “You could use any inert noble gas because rule number one: absolutely no dying [it doesn’t kill organs], and rule number two: no blowing up the lab,” says Jones. In helium, they found a way to uniformly cool an organ and also provide its vasculature with some cushioning so that any stress built up during the cooling process wouldn’t cause a fracture. With helium gas in its veins and arteries, an organ is free to shift as it freezes without shattering, just as skyscrapers are engineered to sway rather than topple in the wind.

When they realized that no one else had tried helium, Arigos was born. And it worked really well. Soon their methods became the only way to successfully freeze and thaw organs from any animal larger than a rabbit.

“We have recovered pig kidneys from temperatures of -120 degrees Celsius, which is basically the glass transition temperature,” Jones says. “We tested on pig hearts, and it worked so well and so quickly that we were unexpectedly unprepared to test the recovery.” To be more prepared in the future, the team is working on automating its processes.

Ideally, the technique could create a universal bank of donated organs so that people could be matched with an organ right when they need it, rather than having to wait their turn in line until a suitable match turns up. Or, at least, it could make it much easier to get organs to the people who need them.

A bank of frozen organs could help solve some of the more banal (but very real) hurdles to transplantation. For example, donors and recipients sometimes have different immune systems. It’s more than just their blood types — before a transplant, doctors need to see how many of the six relevant antigens (molecules that can trigger the immune system into rejecting an organ) match up as well.

With a bank of frozen organs at the ready, doctors would be able to not only save more lives with organ transplants, but they could also more carefully match donated organs and recipients to prevent rejection because a better match could be readily available in the freezer.

But it needs FDA approval to make that happen. The company plans to conduct its first pig transplant in 2019, which it hopes will go well enough to convince the FDA to authorize a human trial in 2020. From there, it will take five to seven years for federal approval.

Others in the organ transplantation community are skeptical that Arigos can achieve everything that it claims to do, especially in the timeframe it set out.

“I would predict it would be longer than that, to actual human trials,” David Klassen, Chief Medical Officer at UNOS, tells Futurism. Normally there needs to be a great deal of animal experimentation before human testing is authorized, Klassen says, and these things take time. “That’s guessing on my part, but I would expect it would be a little longer than two years before human trials.”

But still, Klassen says that that the results coming out of organ freezing research are promising, and that he hopes to see continued interest in freezing organs.

“In broad strokes, I do think it is a top priority and should be. I think from the perspective of clinical transplantation, that whole area is a little underappreciated by people who work in the field day to day,” he says. But in the distant future, he also hopes to see the research community move beyond organ banking and develop ways to 3D print or construct organs from scratch, ultimately eliminating the need for donors in the first place.

But not everyone is convinced that cryopreservation is the future of organ transplantation at all, or that Arigos is the company to do it. Robert Kormos, director of the artificial heart program and co-director of the heart transplantation program at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, told Futurism that he’s skeptical of organ freezing technology.

“I went to [Arigos Biomedical’s] website and there’s a lot of claims of what they’re purporting to do and what they want to do, but usually what companies like this do is give you a list of publications so you can look at what’s been published in this area,” Kormos says. The lack of published research, completed by either by Arigos staff or other researchers in the field at large, raised a red flag for Kormos, who adds that he has not seen a lot of progress in organ freezing research, a field that he’s seen slow down over the decades.

“This company may have something, but again I’m eager to see what science they’re bringing to the table,” he says. “I think cryopreservation is an interesting concept, but we’re a ways away from that being reality. Again, I haven’t seen the data.”

Until their technique is approved, Arigos is working with some collaborators to improve the way scientists develop new pharmaceuticals. Right now, it’s difficult to bring new drugs to the market because many compounds that work great in animal studies don’t work the same way in humans. As a result, one in five phase I clinical trials, the first of three types of experiments conducted on humans before a drug can be approved, typically fails.

Arigos is planning to sell some slices of frozen, donated human organs to pharmaceutical researchers. That could help researchers determine whether or not a drug is toxic to people before they try it in a full-fledged experiment.

“We’ve got some collaborators set up who are going to explore that with us once we get access to human hearts, which we don’t quite yet,” says Jones.

But even if Arigos’ human trials are successful, the company won’t be able to store every type of organ that someone might need. Because their technique requires filling blood vessels with helium, it doesn’t work so well on organs that don’t have blood vessels, so they’ve only been able to freeze and store organs such as kidneys, livers, hearts, and lungs.

The military would love to be able to store entire frozen limbs, but that’s not on the table right now. If a soldier were to lose a limb after being caught in an explosion, it would be helpful to be able to freeze that limb until it’s ready to be reattached. That would give the soldier time to recover before undergoing surgery.

Freezing technology can’t help there yet. Bone tissue doesn’t take up the cryoprotectant solution well. And there are so many different tissue and cell types in a whole limb, each of which has a different tolerance level to the somewhat-toxic vitrification solution, that the technique wouldn’t really work. Arigos’ technique also wouldn’t work on transplantable corneas since they also have no vasculature, so scientists will need to develop new techniques if we want a universal bank of donated organs.

This also means, as Jones explained, that Arigos’ technology will not allow (presumably very rich) people to totally freeze their bodies and re-emerge in the distant future, as so many sci-fi stories have assured us will be possible. No, Arigos’ focus is strictly on medical uses for frozen organs.

If things go the way Arigos hopes, people worldwide could benefit. “There some countries in the world that don’t even have transplant technology,” says Jones. Aside from the immediate benefits to Americans stuck on an endless waitlist for the next kidney, frozen organs could be shipped or stored anywhere, bringing aid to countries and regions where there’s no waitlist at all.

https://futurism.com/freezing-donated-organs-arigos/