False beliefs and wishful thinking about the human experience are common. They are hurting people — and holding back science.

Megan Scudellari

In 1997, physicians in southwest Korea began to offer ultrasound screening for early detection of thyroid cancer. News of the programme spread, and soon physicians around the region began to offer the service. Eventually it went nationwide, piggybacking on a government initiative to screen for other cancers. Hundreds of thousands took the test for just US$30–50.

Across the country, detection of thyroid cancer soared, from 5 cases per 100,000 people in 1999 to 70 per 100,000 in 2011. Two-thirds of those diagnosed had their thyroid glands removed and were placed on lifelong drug regimens, both of which carry risks.

Such a costly and extensive public-health programme might be expected to save lives. But this one did not. Thyroid cancer is now the most common type of cancer diagnosed in South Korea, but the number of people who die from it has remained exactly the same — about 1 per 100,000. Even when some physicians in Korea realized this, and suggested that thyroid screening be stopped in 2014, the Korean Thyroid Association, a professional society of endocrinologists and thyroid surgeons, argued that screening and treatment were basic human rights.

In Korea, as elsewhere, the idea that the early detection of any cancer saves lives had become an unshakeable belief.

This blind faith in cancer screening is an example of how ideas about human biology and behaviour can persist among people — including scientists — even though the scientific evidence shows the concepts to be false. “Scientists think they’re too objective to believe in something as folklore-ish as a myth,” says Nicholas Spitzer, director of the Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind at the University of California, San Diego. Yet they do.

These myths often blossom from a seed of a fact — early detection does save lives for some cancers — and thrive on human desires or anxieties, such as a fear of death. But they can do harm by, for instance, driving people to pursue unnecessary treatment or spend money on unproven products. They can also derail or forestall promising research by distracting scientists or monopolizing funding. And dispelling them is tricky.

Scientists should work to discredit myths, but they also have a responsibility to try to prevent new ones from arising, says Paul Howard-Jones, who studies neuroscience and education at the University of Bristol, UK. “We need to look deeper to understand how they come about in the first place and why they’re so prevalent and persistent.”

Some dangerous myths get plenty of air time: vaccines cause autism, HIV doesn’t cause AIDS. But many others swirl about, too, harming people, sucking up money, muddying the scientific enterprise — or simply getting on scientists’ nerves. Here, Nature looks at the origins and repercussions of five myths that refuse to die.

Myth 1: Screening saves lives for all types of cancer

Regular screening might be beneficial for some groups at risk of certain cancers, such as lung, cervical and colon, but this isn’t the case for all tests. Still, some patients and clinicians defend the ineffective ones fiercely.

The belief that early detection saves lives originated in the early twentieth century, when doctors realized that they got the best outcomes when tumours were identified and treated just after the onset of symptoms. The next logical leap was to assume that the earlier a tumour was found, the better the chance of survival. “We’ve all been taught, since we were at our mother’s knee, the way to deal with cancer is to find it early and cut it out,” says Otis Brawley, chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society.

But evidence from large randomized trials for cancers such as thyroid, prostate and breast has shown that early screening is not the lifesaver it is often advertised as. For example, a Cochrane review of five randomized controlled clinical trials totalling 341,342 participants found that screening did not significantly decrease deaths due to prostate cancer1.

“People seem to imagine the mere fact that you found a cancer so-called early must be a benefit. But that isn’t so at all,” says Anthony Miller at the University of Toronto in Canada. Miller headed the Canadian National Breast Screening Study, a 25-year study of 89,835 women aged 40–59 years old2 that found that annual mammograms did not reduce mortality from breast cancer. That’s because some tumours will lead to death irrespective of when they are detected and treated. Meanwhile, aggressive early screening has a slew of negative health effects. Many cancers grow slowly and will do no harm if left alone, so people end up having unnecessary thyroidectomies, mastectomies and prostatectomies. So on a population level, the benefits (lives saved) do not outweigh the risks (lives lost or interrupted by unnecessary treatment).

Still, individuals who have had a cancer detected and then removed are likely to feel that their life was saved, and these personal experiences help to keep the misconception alive. And oncologists routinely debate what ages and other risk factors would benefit from regular screening.

Focusing so much attention on the current screening tests comes at a cost for cancer research, says Brawley. “In breast cancer, we’ve spent so much time arguing about age 40 versus age 50 and not about the fact that we need a better test,” such as one that could detect fast-growing rather than slow-growing tumours. And existing diagnostics should be rigorously tested to prove that they actually save lives, says epidemiologist John Ioannidis of the Stanford Prevention Research Center in California, who this year reported that very few screening tests for 19 major diseases actually reduced mortality3.

Changing behaviours will be tough. Gilbert Welch at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice in Lebanon, New Hampshire, says that individuals would rather be told to get a quick test every few years than be told to eat well and exercise to prevent cancer. “Screening has become an easy way for both doctor and patient to think they are doing something good for their health, but their risk of cancer hasn’t changed at all.”

Myth 2: Antioxidants are good and free radicals are bad

In December 1945, chemist Denham Harman’s wife suggested that he read an article in Ladies’ Home Journal entitled ‘Tomorrow You May Be Younger’. It sparked his interest in ageing, and years later, as a research associate at the University of California, Berkeley, Harman had a thought “out of the blue”, as he later recalled. Ageing, he proposed, is caused by free radicals, reactive molecules that build up in the body as by-products of metabolism and lead to cellular damage.

Scientists rallied around the free-radical theory of ageing, including the corollary that antioxidants, molecules that neutralize free radicals, are good for human health. By the 1990s, many people were taking antioxidant supplements, such as vitamin C and β-carotene. It is “one of the few scientific theories to have reached the public: gravity, relativity and that free radicals cause ageing, so one needs to have antioxidants”, says Siegfried Hekimi, a biologist at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

Yet in the early 2000s, scientists trying to build on the theory encountered bewildering results: mice genetically engineered to overproduce free radicals lived just as long as normal mice4, and those engineered to overproduce antioxidants didn’t live any longer than normal5. It was the first of an onslaught of negative data, which initially proved difficult to publish. The free-radical theory “was like some sort of creature we were trying to kill. We kept firing bullets into it, and it just wouldn’t die,” says David Gems at University College London, who started to publish his own negative results in 2003 (ref. 6). Then, one study in humans7 showed that antioxidant supplements prevent the health-promoting effects of exercise, and another associated them with higher mortality8.

None of those results has slowed the global antioxidant market, which ranges from food and beverages to livestock feed additives. It is projected to grow from US$2.1 billion in 2013 to $3.1 billion in 2020. “It’s a massive racket,” says Gems. “The reason the notion of oxidation and ageing hangs around is because it is perpetuated by people making money out of it.”

Today, most researchers working on ageing agree that free radicals can cause cellular damage, but that this seems to be a normal part of the body’s reaction to stress. Still, the field has wasted time and resources as a result. And the idea still holds back publications on possible benefits of free radicals, says Michael Ristow, a metabolism researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. “There is a significant body of evidence sitting in drawers and hard drives that supports this concept, but people aren’t putting it out,” he says. “It’s still a major problem.”

Some researchers also question the broader assumption that molecular damage of any kind causes ageing. “There’s a question mark about whether really the whole thing should be chucked out,” says Gems. The trouble, he says, is that “people don’t know where to go now”.

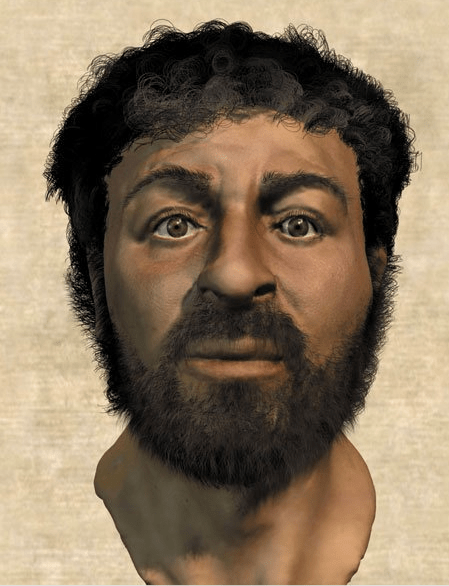

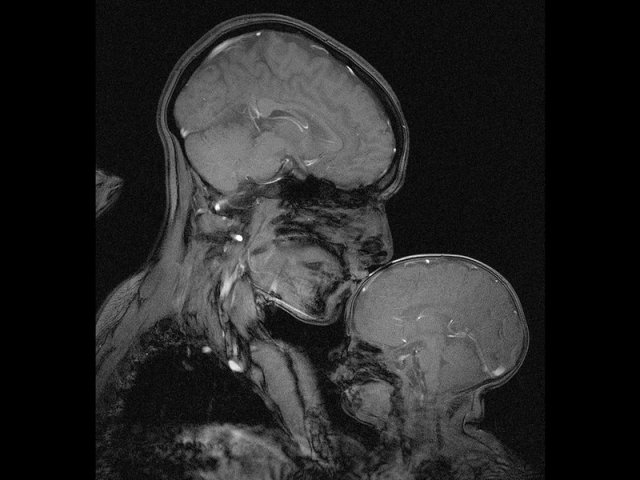

Myth 3: Humans have exceptionally large brains

The human brain — with its remarkable cognition — is often considered to be the pinnacle of brain evolution. That dominance is often attributed to the brain’s exceptionally large size in comparison to the body, as well as its density of neurons and supporting cells, called glia.

None of that, however, is true. “We cherry-pick the numbers that put us on top,” says Lori Marino, a neuroscientist at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. Human brains are about seven times larger than one might expect relative to similarly sized animals. But mice and dolphins have about the same proportions, and some birds have a larger ratio.

“Human brains respect the rules of scaling. We have a scaled-up primate brain,” says Chet Sherwood, a biological anthropologist at George Washington University in Washington DC. Even cell counts have been inflated: articles, reviews and textbooks often state that the human brain has 100 billion neurons. More accurate measures suggest that the number is closer to 86 billion. That may sound like a rounding error, but 14 billion neurons is roughly the equivalent of two macaque brains.

Human brains are different from those of other primates in other ways: Homo sapiens evolved an expanded cerebral cortex — the part of the brain involved in functions such as thought and language — and unique changes in neural structure and function in other areas of the brain.

The myth that our brains are unique because of an exceptional number of neurons has done a disservice to neuroscience because other possible differences are rarely investigated, says Sherwood, pointing to the examples of energy metabolism, rates of brain-cell development and long-range connectivity of neurons. “These are all places where you can find human differences, and they seem to be relatively unconnected to total numbers of neurons,” he says.

The field is starting to explore these topics. Projects such as the US National Institutes of Health’s Human Connectome Project and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne’s Blue Brain Project are now working to understand brain function through wiring patterns rather than size.

Myth 4: Individuals learn best when taught in their preferred learning style

People attribute other mythical qualities to their unexceptionally large brains. One such myth is that individuals learn best when they are taught in the way they prefer to learn. A verbal learner, for example, supposedly learns best through oral instructions, whereas a visual learner absorbs information most effectively through graphics and other diagrams.

There are two truths at the core of this myth: many people have a preference for how they receive information, and evidence suggests that teachers achieve the best educational outcomes when they present information in multiple sensory modes. Couple that with people’s desire to learn and be considered unique, and conditions are ripe for myth-making.

“Learning styles has got it all going for it: a seed of fact, emotional biases and wishful thinking,” says Howard-Jones. Yet just like sugar, pornography and television, “what you prefer is not always good for you or right for you,” says Paul Kirschner, an educational psychologist at the Open University of the Netherlands.

In 2008, four cognitive neuroscientists reviewed the scientific evidence for and against learning styles. Only a few studies had rigorously put the ideas to the test and most of those that did showed that teaching in a person’s preferred style had no beneficial effect on his or her learning. “The contrast between the enormous popularity of the learning-styles approach within education and the lack of credible evidence for its utility is, in our opinion, striking and disturbing,” the authors of one study wrote9.

That hasn’t stopped a lucrative industry from pumping out books and tests for some 71 proposed learning styles. Scientists, too, perpetuate the myth, citing learning styles in more than 360 papers during the past 5 years. “There are groups of researchers who still adhere to the idea, especially folks who developed questionnaires and surveys for categorizing people. They have a strong vested interest,” says Richard Mayer, an educational psychologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

In the past few decades, research into educational techniques has started to show that there are interventions that do improve learning, including getting students to summarize or explain concepts to themselves. And it seems almost all individuals, barring those with learning disabilities, learn best from a mixture of words and graphics, rather than either alone.

Yet the learning-styles myth makes it difficult to get these evidence-backed concepts into classrooms. When Howard-Jones speaks to teachers to dispel the learning-styles myth, for example, they often don’t like to hear what he has to say. “They have disillusioned faces. Teachers invested hope, time and effort in these ideas,” he says. “After that, they lose interest in the idea that science can support learning and teaching.”

Myth 5: The human population is growing exponentially (and we’re doomed)

Fears about overpopulation began with Reverend Thomas Malthus in 1798, who predicted that unchecked exponential population growth would lead to famine and poverty.

But the human population has not and is not growing exponentially and is unlikely to do so, says Joel Cohen, a populations researcher at the Rockefeller University in New York City. The world’s population is now growing at just half the rate it was before 1965. Today there are an estimated 7.3 billion people, and that is projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050. Yet beliefs that the rate of population growth will lead to some doomsday scenario have been continually perpetuated. Celebrated physicist Albert Bartlett, for example, gave more than 1,742 lectures on exponential human population growth and the dire consequences starting in 1969.

The world’s population also has enough to eat. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the rate of global food production outstrips the growth of the population. People grow enough calories in cereals alone to feed between 10 billion and 12 billion people. Yet hunger and malnutrition persist worldwide. This is because about 55% of the food grown is divided between feeding cattle, making fuel and other materials or going to waste, says Cohen. And what remains is not evenly distributed — the rich have plenty, the poor have little. Likewise, water is not scarce on a global scale, even though 1.2 billion people live in areas where it is.

“Overpopulation is really not overpopulation. It’s a question about poverty,” says Nicholas Eberstadt, a demographer at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank based in Washington DC. Yet instead of examining why poverty exists and how to sustainably support a growing population, he says, social scientists and biologists talk past each other, debating definitions and causes of overpopulation.

Cohen adds that “even people who know the facts use it as an excuse not to pay attention to the problems we have right now”, pointing to the example of economic systems that favour the wealthy.

Like others interviewed for this article, Cohen is less than optimistic about the chances of dispelling the idea of overpopulation and other ubiquitous myths (see ‘Myths that persist’), but he agrees that it is worthwhile to try to prevent future misconceptions. Many myths have emerged after one researcher extrapolated beyond the narrow conclusions of another’s work, as was the case for free radicals. That “interpretation creep”, as Spitzer calls it, can lead to misconceptions that are hard to excise. To prevent that, “we can make sure an extrapolation is justified, that we’re not going beyond the data”, suggests Spitzer. Beyond that, it comes down to communication, says Howard-Jones. Scientists need to be effective at communicating ideas and get away from simple, boiled-down messages.

Once a myth is here, it is often here to stay. Psychological studies suggest that the very act of attempting to dispel a myth leads to stronger attachment to it. In one experiment, exposure to pro-vaccination messages reduced parents’ intention to vaccinate their children in the United States. In another, correcting misleading claims from politicians increased false beliefs among those who already held them. “Myths are almost impossible to eradicate,” says Kirschner. “The more you disprove it, often the more hard core it becomes.”

http://www.nature.com/news/the-science-myths-that-will-not-die-1.19022

Nature 528, 322–325 (17 December 2015) doi:10.1038/528322a

1.Ilic, D., Neuberger, M. M., Djulbegovic, M. & Dahm, P. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, CD004720 (2013).

2.Miller, A. B. et al. Br. Med. J. 348, g366 (2014).

3.Saquib, N., Saquib, J. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 264–277 (2015).

4.Doonan, R. et al. Genes Dev. 22, 3236–3241 (2008).

5.Pérez, V. I. et al. Aging Cell 8, 73–75 (2009).

6.Keaney, M. & Gems, D. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 34, 277–282 (2003).

7.Ristow, M. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8665–8670 (2009).

8.Bjelakovic, G., Nikolova, D. & Gluud, C. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 310, 1178–1179 (2013).

9.Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D. & Bjork, R. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 9, 105–119 (2008).