by Jerry Useem

If power were a prescription drug, it would come with a long list of known side effects. It can intoxicate. It can corrupt. It can even make Henry Kissinger believe that he’s sexually magnetic. But can it cause brain damage?

When various lawmakers lit into John Stumpf at a congressional hearing last fall, each seemed to find a fresh way to flay the now-former CEO of Wells Fargo for failing to stop some 5,000 employees from setting up phony accounts for customers. But it was Stumpf’s performance that stood out. Here was a man who had risen to the top of the world’s most valuable bank, yet he seemed utterly unable to read a room. Although he apologized, he didn’t appear chastened or remorseful. Nor did he seem defiant or smug or even insincere. He looked disoriented, like a jet-lagged space traveler just arrived from Planet Stumpf, where deference to him is a natural law and 5,000 a commendably small number. Even the most direct barbs—“You have got to be kidding me” (Sean Duffy of Wisconsin); “I can’t believe some of what I’m hearing here” (Gregory Meeks of New York)—failed to shake him awake.

What was going through Stumpf’s head? New research suggests that the better question may be: What wasn’t going through it?

The historian Henry Adams was being metaphorical, not medical, when he described power as “a sort of tumor that ends by killing the victim’s sympathies.” But that’s not far from where Dacher Keltner, a psychology professor at UC Berkeley, ended up after years of lab and field experiments. Subjects under the influence of power, he found in studies spanning two decades, acted as if they had suffered a traumatic brain injury—becoming more impulsive, less risk-aware, and, crucially, less adept at seeing things from other people’s point of view.

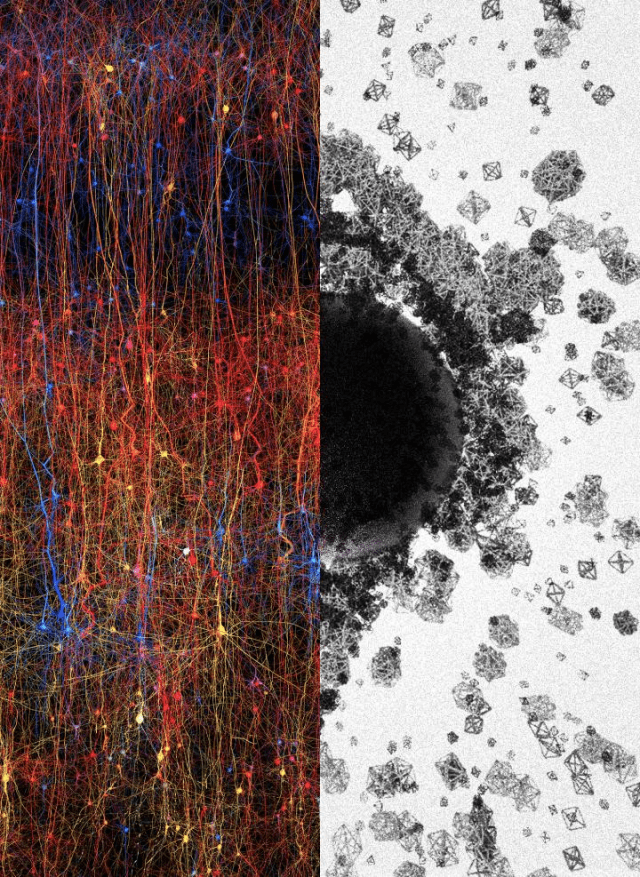

Sukhvinder Obhi, a neuroscientist at McMaster University, in Ontario, recently described something similar. Unlike Keltner, who studies behaviors, Obhi studies brains. And when he put the heads of the powerful and the not-so-powerful under a transcranial-magnetic-stimulation machine, he found that power, in fact, impairs a specific neural process, “mirroring,” that may be a cornerstone of empathy. Which gives a neurological basis to what Keltner has termed the “power paradox”: Once we have power, we lose some of the capacities we needed to gain it in the first place.

That loss in capacity has been demonstrated in various creative ways. A 2006 study asked participants to draw the letter E on their forehead for others to view—a task that requires seeing yourself from an observer’s vantage point. Those feeling powerful were three times more likely to draw the E the right way to themselves—and backwards to everyone else (which calls to mind George W. Bush, who memorably held up the American flag backwards at the 2008 Olympics). Other experiments have shown that powerful people do worse at identifying what someone in a picture is feeling, or guessing how a colleague might interpret a remark.

The fact that people tend to mimic the expressions and body language of their superiors can aggravate this problem: Subordinates provide few reliable cues to the powerful. But more important, Keltner says, is the fact that the powerful stop mimicking others. Laughing when others laugh or tensing when others tense does more than ingratiate. It helps trigger the same feelings those others are experiencing and provides a window into where they are coming from. Powerful people “stop simulating the experience of others,” Keltner says, which leads to what he calls an “empathy deficit.”

Mirroring is a subtler kind of mimicry that goes on entirely within our heads, and without our awareness. When we watch someone perform an action, the part of the brain we would use to do that same thing lights up in sympathetic response. It might be best understood as vicarious experience. It’s what Obhi and his team were trying to activate when they had their subjects watch a video of someone’s hand squeezing a rubber ball.

For nonpowerful participants, mirroring worked fine: The neural pathways they would use to squeeze the ball themselves fired strongly. But the powerful group’s? Less so.

Was the mirroring response broken? More like anesthetized. None of the participants possessed permanent power. They were college students who had been “primed” to feel potent by recounting an experience in which they had been in charge. The anesthetic would presumably wear off when the feeling did—their brains weren’t structurally damaged after an afternoon in the lab. But if the effect had been long-lasting—say, by dint of having Wall Street analysts whispering their greatness quarter after quarter, board members offering them extra helpings of pay, and Forbes praising them for “doing well while doing good”—they may have what in medicine is known as “functional” changes to the brain.

I wondered whether the powerful might simply stop trying to put themselves in others’ shoes, without losing the ability to do so. As it happened, Obhi ran a subsequent study that may help answer that question. This time, subjects were told what mirroring was and asked to make a conscious effort to increase or decrease their response. “Our results,” he and his co-author, Katherine Naish, wrote, “showed no difference.” Effort didn’t help.

This is a depressing finding. Knowledge is supposed to be power. But what good is knowing that power deprives you of knowledge?

The sunniest possible spin, it seems, is that these changes are only sometimes harmful. Power, the research says, primes our brain to screen out peripheral information. In most situations, this provides a helpful efficiency boost. In social ones, it has the unfortunate side effect of making us more obtuse. Even that is not necessarily bad for the prospects of the powerful, or the groups they lead. As Susan Fiske, a Princeton psychology professor, has persuasively argued, power lessens the need for a nuanced read of people, since it gives us command of resources we once had to cajole from others. But of course, in a modern organization, the maintenance of that command relies on some level of organizational support. And the sheer number of examples of executive hubris that bristle from the headlines suggests that many leaders cross the line into counterproductive folly.

Less able to make out people’s individuating traits, they rely more heavily on stereotype. And the less they’re able to see, other research suggests, the more they rely on a personal “vision” for navigation. John Stumpf saw a Wells Fargo where every customer had eight separate accounts. (As he’d often noted to employees, eight rhymes with great.) “Cross-selling,” he told Congress, “is shorthand for deepening relationships.”

Is there nothing to be done?

No and yes. It’s difficult to stop power’s tendency to affect your brain. What’s easier—from time to time, at least—is to stop feeling powerful.

Insofar as it affects the way we think, power, Keltner reminded me, is not a post or a position but a mental state. Recount a time you did not feel powerful, his experiments suggest, and your brain can commune with reality.

Recalling an early experience of powerlessness seems to work for some people—and experiences that were searing enough may provide a sort of permanent protection. An incredible study published in The Journal of Finance last February found that CEOs who as children had lived through a natural disaster that produced significant fatalities were much less risk-seeking than CEOs who hadn’t. (The one problem, says Raghavendra Rau, a co-author of the study and a Cambridge University professor, is that CEOs who had lived through disasters without significant fatalities were more risk-seeking.)

But tornadoes, volcanoes, and tsunamis aren’t the only hubris-restraining forces out there. PepsiCo CEO and Chairman Indra Nooyi sometimes tells the story of the day she got the news of her appointment to the company’s board, in 2001. She arrived home percolating in her own sense of importance and vitality, when her mother asked whether, before she delivered her “great news,” she would go out and get some milk. Fuming, Nooyi went out and got it. “Leave that damn crown in the garage” was her mother’s advice when she returned.

The point of the story, really, is that Nooyi tells it. It serves as a useful reminder about ordinary obligation and the need to stay grounded. Nooyi’s mother, in the story, serves as a “toe holder,” a term once used by the political adviser Louis Howe to describe his relationship with the four-term President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whom Howe never stopped calling Franklin.

For Winston Churchill, the person who filled that role was his wife, Clementine, who had the courage to write, “My Darling Winston. I must confess that I have noticed a deterioration in your manner; & you are not as kind as you used to be.” Written on the day Hitler entered Paris, torn up, then sent anyway, the letter was not a complaint but an alert: Someone had confided to her, she wrote, that Churchill had been acting “so contemptuous” toward subordinates in meetings that “no ideas, good or bad, will be forthcoming”—with the attendant danger that “you won’t get the best results.”

Lord David Owen—a British neurologist turned parliamentarian who served as the foreign secretary before becoming a baron—recounts both Howe’s story and Clementine Churchill’s in his 2008 book, In Sickness and in Power, an inquiry into the various maladies that had affected the performance of British prime ministers and American presidents since 1900. While some suffered from strokes (Woodrow Wilson), substance abuse (Anthony Eden), or possibly bipolar disorder (Lyndon B. Johnson, Theodore Roosevelt), at least four others acquired a disorder that the medical literature doesn’t recognize but, Owen argues, should.

“Hubris syndrome,” as he and a co-author, Jonathan Davidson, defined it in a 2009 article published in Brain, “is a disorder of the possession of power, particularly power which has been associated with overwhelming success, held for a period of years and with minimal constraint on the leader.” Its 14 clinical features include: manifest contempt for others, loss of contact with reality, restless or reckless actions, and displays of incompetence. In May, the Royal Society of Medicine co-hosted a conference of the Daedalus Trust—an organization that Owen founded for the study and prevention of hubris.

I asked Owen, who admits to a healthy predisposition to hubris himself, whether anything helps keep him tethered to reality, something that other truly powerful figures might emulate. He shared a few strategies: thinking back on hubris-dispelling episodes from his past; watching documentaries about ordinary people; making a habit of reading constituents’ letters.

But I surmised that the greatest check on Owen’s hubris today might stem from his recent research endeavors. Businesses, he complained to me, had shown next to no appetite for research on hubris. Business schools were not much better. The undercurrent of frustration in his voice attested to a certain powerlessness. Whatever the salutary effect on Owen, it suggests that a malady seen too commonly in boardrooms and executive suites is unlikely to soon find a cure.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/07/power-causes-brain-damage/528711/