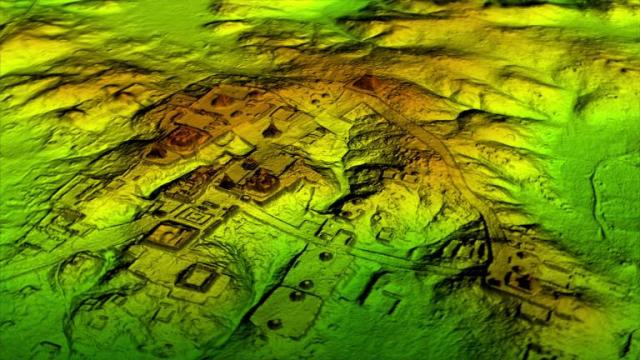

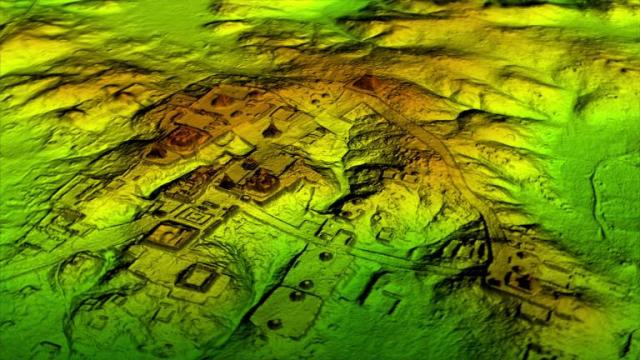

Laser technology known as LiDAR digitally removes the forest canopy to reveal ancient ruins below, showing that Maya cities such as Tikal were much larger than ground-based research had suggested.

By Tom Clynes

In what’s being hailed as a “major breakthrough” in Maya archaeology, researchers have identified the ruins of more than 60,000 houses, palaces, elevated highways, and other human-made features that have been hidden for centuries under the jungles of northern Guatemala.

Laser scans revealed more than 60,000 previously unknown Maya structures that were part of a vast network of cities, fortifications, farms, and highways.

Using a revolutionary technology known as LiDAR (short for “Light Detection And Ranging”), scholars digitally removed the tree canopy from aerial images of the now-unpopulated landscape, revealing the ruins of a sprawling pre-Columbian civilization that was far more complex and interconnected than most Maya specialists had supposed.

“The LiDAR images make it clear that this entire region was a settlement system whose scale and population density had been grossly underestimated,” said Thomas Garrison, an Ithaca College archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer who specializes in using digital technology for archaeological research.

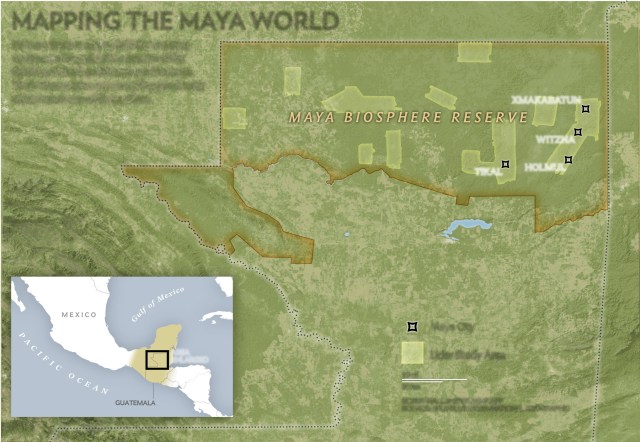

Garrison is part of a consortium of researchers who are participating in the project, which was spearheaded by the PACUNAM Foundation, a Guatemalan nonprofit that fosters scientific research, sustainable development, and cultural heritage preservation.

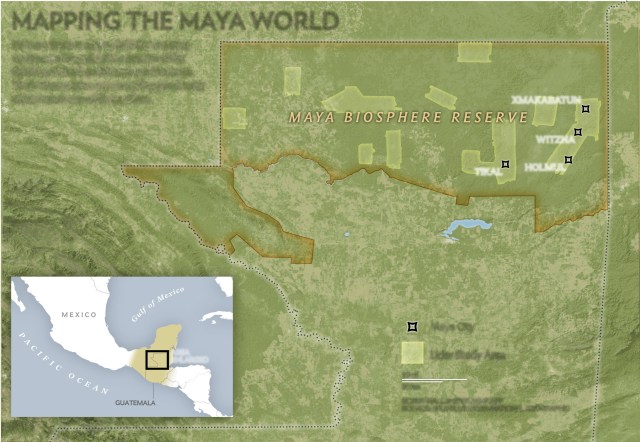

The project mapped more than 800 square miles (2,100 square kilometers) of the Maya Biosphere Reserve in the Petén region of Guatemala, producing the largest LiDAR data set ever obtained for archaeological research.

The results suggest that Central America supported an advanced civilization that was, at its peak some 1,200 years ago, more comparable to sophisticated cultures such as ancient Greece or China than to the scattered and sparsely populated city states that ground-based research had long suggested.

In addition to hundreds of previously unknown structures, the LiDAR images show raised highways connecting urban centers and quarries. Complex irrigation and terracing systems supported intensive agriculture capable of feeding masses of workers who dramatically reshaped the landscape.

The ancient Maya never used the wheel or beasts of burden, yet “this was a civilization that was literally moving mountains,” said Marcello Canuto, a Tulane University archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer who participated in the project.

“We’ve had this western conceit that complex civilizations can’t flourish in the tropics, that the tropics are where civilizations go to die,” said Canuto, who conducts archaeological research at a Guatemalan site known as La Corona. “But with the new LiDAR-based evidence from Central America and [Cambodia’s] Angkor Wat, we now have to consider that complex societies may have formed in the tropics and made their way outward from there.”

“LiDAR is revolutionizing archaeology the way the Hubble Space Telescope revolutionized astronomy,” said Francisco Estrada-Belli, a Tulane University archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer. “We’ll need 100 years to go through all [the data] and really understand what we’re seeing.”

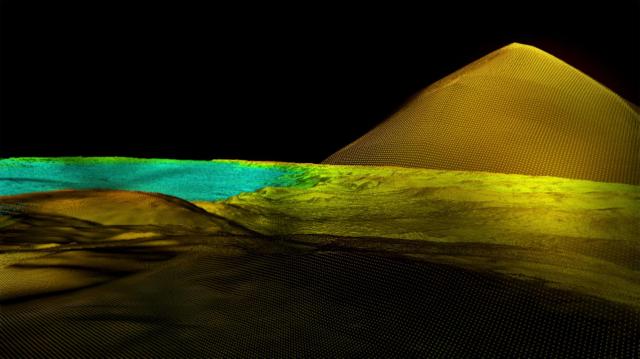

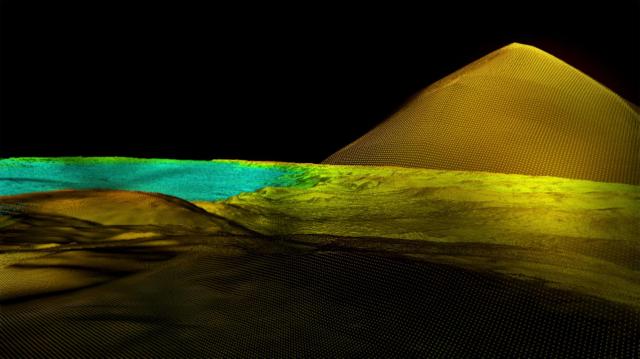

The unaided eye sees only jungle and an overgrown mound, but LiDAR and augmented reality software reveal an ancient Maya pyramid.

Already, though, the survey has yielded surprising insights into settlement patterns, inter-urban connectivity, and militarization in the Maya Lowlands. At its peak in the Maya classic period (approximately A.D. 250–900), the civilization covered an area about twice the size of medieval England, but it was far more densely populated.

“Most people had been comfortable with population estimates of around 5 million,” said Estrada-Belli, who directs a multi-disciplinary archaeological project at Holmul, Guatemala. “With this new data it’s no longer unreasonable to think that there were 10 to 15 million people there—including many living in low-lying, swampy areas that many of us had thought uninhabitable.”

Hidden deep in the jungle, the newly-discovered pyramid rises some seven stories high but is nearly invisible to the naked eye.

Virtually all the Mayan cities were connected by causeways wide enough to suggest that they were heavily trafficked and used for trade and other forms of regional interaction. These highways were elevated to allow easy passage even during rainy seasons. In a part of the world where there is usually too much or too little precipitation, the flow of water was meticulously planned and controlled via canals, dikes, and reservoirs.

Among the most surprising findings was the ubiquity of defensive walls, ramparts, terraces, and fortresses. “Warfare wasn’t only happening toward the end of the civilization,” said Garrison. “It was large-scale and systematic, and it endured over many years.”

The survey also revealed thousands of pits dug by modern-day looters. “Many of these new sites are only new to us; they are not new to looters,” said Marianne Hernandez, president of the PACUNAM Foundation. (Read “Losing Maya Heritage to Looters.”)

Environmental degradation is another concern. Guatemala is losing more than 10 percent of its forests annually, and habitat loss has accelerated along its border with Mexico as trespassers burn and clear land for agriculture and human settlement.

“By identifying these sites and helping to understand who these ancient people were, we hope to raise awareness of the value of protecting these places,” Hernandez said.

The survey is the first phase of the PACUNAM LiDAR Initiative, a three-year project that will eventually map more than 5,000 square miles (14,000 square kilometers) of Guatemala’s lowlands, part of a pre-Columbian settlement system that extended north to the Gulf of Mexico.

“The ambition and the impact of this project is just incredible,” said Kathryn Reese-Taylor, a University of Calgary archaeologist and Maya specialist who was not associated with the PACUNAM survey. “After decades of combing through the forests, no archaeologists had stumbled across these sites. More importantly, we never had the big picture that this data set gives us. It really pulls back the veil and helps us see the civilization as the ancient Maya saw it.”

https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/02/maya-laser-lidar-guatemala-pacunam/

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the It’s Interesting community.