The hallowed notion that oxidative damage causes aging and that vitamins might preserve our youth is now in doubt.

•For decades researchers assumed that highly reactive molecules called free radicals caused aging by damaging cells and thus undermining the functioning of tissues and organs.

•Recent experiments, however, show that increases in certain free radicals in mice and worms correlate with longer life span. Indeed, in some circumstances, free radicals seem to signal cellular repair networks.

•If these results are confirmed, they may suggest that taking antioxidants in the form of vitamins or other supplements can do more harm than good in otherwise healthy individuals.

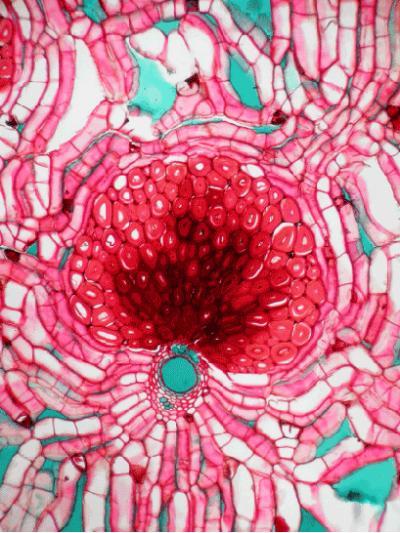

David Gems’s life was turned upside down in 2006 by a group of worms that kept on living when they were supposed to die. As assistant director of the Institute of Healthy Aging at University College London, Gems regularly runs experiments on Caenorhabditis elegans, a roundworm that is often used to study the biology of aging. In this case, he was testing the idea that a buildup of cellular damage caused by oxidation—technically, the chemical removal of electrons from a molecule by highly reactive compounds, such as free radicals—is the main mechanism behind aging. According to this theory, rampant oxidation mangles more and more lipids, proteins, snippets of DNA and other key components of cells over time, eventually compromising tissues and organs and thus the functioning of the body as a whole.

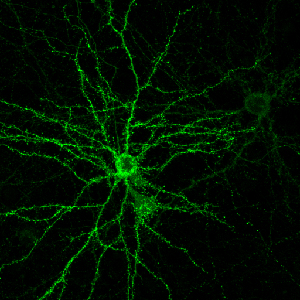

Gems genetically engineered the roundworms so they no longer produced certain enzymes that act as naturally occurring antioxidants by deactivating free radicals. Sure enough, in the absence of the antioxidants, levels of free radicals in the worms skyrocketed and triggered potentially damaging oxidative reactions throughout the worms’ bodies.

Contrary to Gems’s expectations, however, the mutant worms did not die prematurely. Instead they lived just as long as normal worms did. The researcher was mystified. “I said, ‘Come on, this can’t be right,’” he recalls. “‘Obviously something’s gone wrong here.’” He asked another investigator in his laboratory to check the results and do the experiment again. Nothing changed. The experimental worms did not produce these particular antioxidants; they accumulated free radicals as predicted, and yet they did not die young—despite suffering extreme oxidative damage.

Other scientists were finding similarly confounding results in different lab animals. In the U.S., Arlan Richardson, director of the Barshop Institute for Longevity and Aging Studies at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, genetically engineered 18 different strains of mice, some of which produced more of certain antioxidant enzymes than normal and some of which produced fewer of them than normal. If the damage caused by free radical production and subsequent oxidation was responsible for aging, then the mice with extra antioxidants in their bodies should have lived longer than the mice missing their antioxidant enzymes. Yet “I watched those goddamn life span curves, and there was not an inch of difference between them,” Richardson says. He published his increasingly bewildering results in a series of papers between 2001 and 2009.

Meanwhile, a few doors down the hall from Richardson, physiologist Rochelle Buffenstein has spent the past 11 years trying to understand why the longest-living rodent, the naked mole rat, is able to survive up to 25 to 30 years—around eight times longer than a similarly sized mouse. Buffenstein’s experiments have shown that naked mole rats possess lower levels of natural antioxidants than mice and accumulate more oxidative damage to their tissues at an earlier age than other rodents. Yet paradoxically, they live virtually disease-free until they die at a very old age.

To proponents of the long-standing oxidative damage theory of aging, these findings are nothing short of heretical. They are, however, becoming less the exception and more the rule. Over the course of the past decade, many experiments designed to further support the idea that free radicals and other reactive molecules drive aging have instead directly challenged it. What is more, it seems that in certain amounts and situations, these high-energy molecules may not be dangerous but useful and healthy, igniting intrinsic defense mechanisms that keep our bodies in tip-top shape. These ideas not only have drastic implications for future antiaging interventions, but they also raise questions about the common wisdom of popping high doses of antioxidant vitamins. If the oxidative-damage theory is wrong, then aging is even more complicated than researchers thought—and they may ultimately need to revise their understanding of what healthy aging looks like on the molecular level.

“The field of aging has been gliding along on this set of paradigms, ideas about what aging is, that to some extent were kind of plucked out of the air,” Gems says. “We should probably be looking at other theories as well and considering, fundamentally, that we might have to look completely differently at biology.”

The Birth of a Radical Theory

The oxidative damage, or free radical, theory of aging can be traced back to Denham Harman, who found his true calling in December 1945, thanks to the Ladies’ Home Journal. His wife, Helen, brought a copy of the magazine home and pointed out an article on the potential causes of aging, which he read. It fascinated him.

Back then, the 29-year-old chemist was working at Shell Development, the research arm of Shell Oil, and he did not have much time to ponder the issue. Yet nine years later, after graduating from medical school and completing his training, he took a job as a research associate at the University of California, Berkeley, and began contemplating the science of aging more seriously. One morning while sitting in his office, he had an epiphany—“you know just ‘out the blue,’” he recalled in a 2003 interview: aging must be driven by free radicals.

Although free radicals had never before been linked to aging, it made sense to Harman that they might be the culprit. For one thing, he knew that ionizing radiation from x-rays and radioactive bombs, which can be deadly, sparks the production of free radicals in the body. Studies at the time suggested that diets rich in food-based antioxidants muted radiation’s ill effects, suggesting—correctly, as it turned out—that the radicals were a cause of those effects. Moreover, free radicals were normal by-products of breathing and metabolism and built up in the body over time. Because both cellular damage and free radical levels increased with age, free radicals probably caused the damage that was responsible for aging, Harman thought—and antioxidants probably slowed it.

Harman started testing his hypothesis. In one of his first experiments, he fed mice antioxidants and showed that they lived longer. (At high concentrations, however, the antioxidants had deleterious effects.) Other scientists soon began testing it, too. In 1969 researchers at Duke University discovered the first antioxidant enzyme produced inside the body—superoxide dismutase—and speculated that it evolved to counter the deleterious effects of free radical accumulation. With these new data, most biologists began accepting the idea. “If you work in aging, it’s like the air you breathe is the free radical theory,” Gems says. “It’s ubiquitous, it’s in every textbook. Every paper seems to refer to it either indirectly or directly.”

Still, over time scientists had trouble replicating some of Harman’s experimental findings. By the 1970s “there wasn’t a robust demonstration that feeding animals antioxidants really had an effect on life span,” Richardson says. He assumed that the conflicting experiments—which had been done by other scientists—simply had not been controlled very well. Perhaps the animals could not absorb the antioxidants that they had been fed, and thus the overall level of free radicals in their blood had not changed. By the 1990s, however, genetic advances allowed scientists to test the effects of antioxidants in a more precise way—by directly manipulating genomes to change the amount of antioxidant enzymes animals were capable of producing. Time and again, Richardson’s experiments with genetically modified mice showed that the levels of free radical molecules circulating in the animals’ bodies—and subsequently the amount of oxidative damage they endured—had no bearing on how long they lived.

More recently, Siegfried Hekimi, a biologist at McGill University, has bred roundworms that overproduce a specific free radical known as superoxide. “I thought they were going to help us prove the theory that oxidative stress causes aging,” says Hekimi, who had predicted that the worms would die young. Instead he reported in a 2010 paper in PLOS Biology that the engineered worms did not develop high levels of oxidative damage and that they lived, on average, 32 percent longer than normal worms. Indeed, treating these genetically modified worms with the antioxidant vitamin C prevented this increase in life span. Hekimi speculates that superoxide acts not as a destructive molecule but as a protective signal in the worms’ bodies, turning up the expression of genes that help to repair cellular damage.

In a follow-up experiment, Hekimi exposed normal worms, from birth, to low levels of a common weed-controlling herbicide that initiates free radical production in animals as well as plants. In the same 2010 paper he reported the counterintuitive result: the toxin-bathed worms lived 58 percent longer than untreated worms. Again, feeding the worms antioxidants quenched the toxin’s beneficial effects. Finally, in April 2012, he and his colleagues showed that knocking out, or deactivating, all five of the genes that code for superoxide dismutase enzymes in worms has virtually no effect on worm life span.

Do these discoveries mean that the free radical theory is flat-out wrong? Simon Melov, a biochemist at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging in Novato, Calif., believes that the issue is unlikely to be so simple; free radicals may be beneficial in some contexts and dangerous in others. Large amounts of oxidative damage have indisputably been shown to cause cancer and organ damage, and plenty of evidence indicates that oxidative damage plays a role in the development of some chronic conditions, such as heart disease. In addition, researchers at the University of Washington have demonstrated that mice live longer when they are genetically engineered to produce high levels of an antioxidant known as catalase. Saying that something, like oxidative damage, contributes to aging in certain instances, however, is “a very different thing than saying that it drives the pathology,” Melov notes. Aging probably is not a monolithic entity with a single cause and a single cure, he argues, and it was wishful thinking to ever suppose it was one.

Shifting Perspective

Assuming free radicals accumulate during aging but do not necessarily cause it, what effects do they have? So far that question has led to more speculation than definitive data.

“They’re actually part of the defense mechanism,” Hekimi asserts. Free radicals might, in some cases, be produced in response to cellular damage—as a way to signal the body’s own repair mechanisms, for example. In this scenario, free radicals are a consequence of age-related damage, not a cause of it. In large amounts, however, Hekimi says, free radicals may create damage as well.

The general idea that minor insults might help the body withstand bigger ones is not new. Indeed, that is how muscles grow stronger in response to a steady increase in the amount of strain that is placed on them. Many occasional athletes, on the other hand, have learned from painful firsthand experience that an abrupt increase in the physical demands they place on their body after a long week of sitting at an office desk is instead almost guaranteed to lead to pulled calves and hamstrings, among other significant injuries.

In 2002 researchers at the University of Colorado at Boulder briefly exposed worms to heat or to chemicals that induced the production of free radicals, showing that the environmental stressors each boosted the worms’ ability to survive larger insults later. The interventions also increased the worms’ life expectancy by 20 percent. It is unclear how these interventions affected overall levels of oxidative damage, however, because the investigators did not assess these changes. In 2010 researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, and Pohang University of Science and Technology in South Korea reported in Current Biology that some free radicals turn on a gene called HIF-1 that is itself responsible for activating a number of genes involved in cellular repair, including one that helps to repair mutated DNA.

Free radicals may also explain in part why exercise is beneficial. For years researchers assumed that exercise was good in spite of the fact that it produces free radicals, not because of it. Yet in a 2009 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Michael Ristow, a nutrition professor at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena in Germany, and his colleagues compared the physiological profiles of exercisers who took antioxidants with exercisers who did not. Echoing Richardson’s results in mice, Ristow found that the exercisers who did not pop vitamins were healthier than those who did; among other things, the unsupplemented athletes showed fewer signs that they might develop type 2 diabetes. Research by Beth Levine, a microbiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, has shown that exercise also ramps up a biological process called autophagy, in which cells recycle worn-out bits of proteins and other subcellular pieces. The tool used to digest and disassemble the old molecules: free radicals. Just to complicate matters a bit, however, Levine’s research indicates that autophagy also reduces the overall level of free radicals, suggesting that the types and amounts of free radicals in different parts of the cell may play various roles, depending on the circumstances.

The Antioxidant Myth

If free radicals are not always bad, then their antidotes, antioxidants, may not always be good—a worrisome possibility given that 52 percent of Americans take considerable doses of antioxidants daily, such as vitamin E and beta-carotene, in the form of multivitamin supplements. In 2007 the Journal of the American Medical Association published a systematic review of 68 clinical trials, which concluded that antioxidant supplements do not reduce risk of death. When the authors limited their review to the trials that were least likely to be affected by bias—those in which assignment of participants to their research arms was clearly random and neither investigators nor participants knew who was getting what pill, for instance—they found that certain antioxidants were linked to an increased risk of death, in some cases by up to 16 percent.

Several U.S. organizations, including the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association, now advise that people should not take antioxidant supplements except to treat a diagnosed vitamin deficiency. “The literature is providing growing evidence that these supplements—in particular, at high doses—do not necessarily have the beneficial effects that they have been thought to,” says Demetrius Albanes, a senior investigator at the Nutritional Epidemiology Branch of the National Cancer Institute. Instead, he says, “we’ve become acutely aware of potential downsides.”

It is hard to imagine, however, that antioxidants will ever fall out of favor completely—or that most researchers who study aging will become truly comfortable with the idea of beneficial free radicals without a lot more proof. Yet slowly, it seems, the evidence is beginning to suggest that aging is far more intricate and complex than Harman imagined it to be nearly 60 years ago. Gems, for one, believes the evidence points to a new theory in which aging stems from the overactivity of certain biological processes involved in growth and reproduction. But no matter what idea (or ideas) scientists settle on, moving forward, “the constant drilling away of scientists at the facts is shifting the field into a slightly stranger, but a bit more real, place,” Gems says. “It’s an amazing breath of fresh air.”

http://www.nature.com/scientificamerican/journal/v308/n2/full/scientificamerican0213-62.html