t’s been almost 20 years since IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer beat the reigning world chess champion, Gary Kasparov, for the first time under standard tournament rules. Since then, chess-playing computers have become significantly stronger, leaving the best humans little chance even against a modern chess engine running on a smartphone.

But while computers have become faster, the way chess engines work has not changed. Their power relies on brute force, the process of searching through all possible future moves to find the best next one.

Of course, no human can match that or come anywhere close. While Deep Blue was searching some 200 million positions per second, Kasparov was probably searching no more than five a second. And yet he played at essentially the same level. Clearly, humans have a trick up their sleeve that computers have yet to master.

This trick is in evaluating chess positions and narrowing down the most profitable avenues of search. That dramatically simplifies the computational task because it prunes the tree of all possible moves to just a few branches.

Computers have never been good at this, but today that changes thanks to the work of Matthew Lai at Imperial College London. Lai has created an artificial intelligence machine called Giraffe that has taught itself to play chess by evaluating positions much more like humans and in an entirely different way to conventional chess engines.

Straight out of the box, the new machine plays at the same level as the best conventional chess engines, many of which have been fine-tuned over many years. On a human level, it is equivalent to FIDE International Master status, placing it within the top 2.2 percent of tournament chess players.

The technology behind Lai’s new machine is a neural network. This is a way of processing information inspired by the human brain. It consists of several layers of nodes that are connected in a way that change as the system is trained. This training process uses lots of examples to fine-tune the connections so that the network produces a specific output given a certain input, to recognize the presence of face in a picture, for example.

In the last few years, neural networks have become hugely powerful thanks to two advances. The first is a better understanding of how to fine-tune these networks as they learn, thanks in part to much faster computers. The second is the availability of massive annotated datasets to train the networks.

That has allowed computer scientists to train much bigger networks organized into many layers. These so-called deep neural networks have become hugely powerful and now routinely outperform humans in pattern recognition tasks such as face recognition and handwriting recognition.

So it’s no surprise that deep neural networks ought to be able to spot patterns in chess and that’s exactly the approach Lai has taken. His network consists of four layers that together examine each position on the board in three different ways.

The first looks at the global state of the game, such as the number and type of pieces on each side, which side is to move, castling rights and so on. The second looks at piece-centric features such as the location of each piece on each side, while the final aspect is to map the squares that each piece attacks and defends.

Lai trains his network with a carefully generated set of data taken from real chess games. This data set must have the correct distribution of positions. “For example, it doesn’t make sense to train the system on positions with three queens per side, because those positions virtually never come up in actual games,” he says.

It must also have plenty of variety of unequal positions beyond those that usually occur in top level chess games. That’s because although unequal positions rarely arise in real chess games, they crop up all the time in the searches that the computer performs internally.

And this data set must be huge. The massive number of connections inside a neural network have to be fine-tuned during training and this can only be done with a vast dataset. Use a dataset that is too small and the network can settle into a state that fails to recognize the wide variety of patterns that occur in the real world.

Lai generated his dataset by randomly choosing five million positions from a database of computer chess games. He then created greater variety by adding a random legal move to each position before using it for training. In total he generated 175 million positions in this way.

The usual way of training these machines is to manually evaluate every position and use this information to teach the machine to recognize those that are strong and those that are weak.

But this is a huge task for 175 million positions. It could be done by another chess engine but Lai’s goal was more ambitious. He wanted the machine to learn itself.

Instead, he used a bootstrapping technique in which Giraffe played against itself with the goal of improving its prediction of its own evaluation of a future position. That works because there are fixed reference points that ultimately determine the value of a position—whether the game is later won, lost or drawn.

In this way, the computer learns which positions are strong and which are weak.

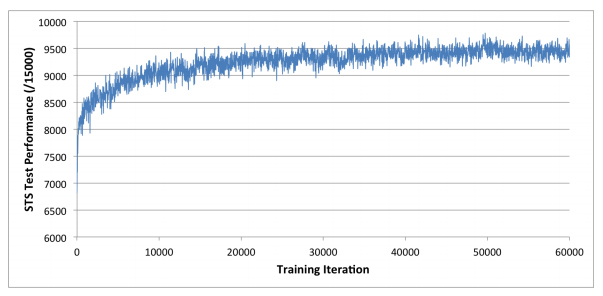

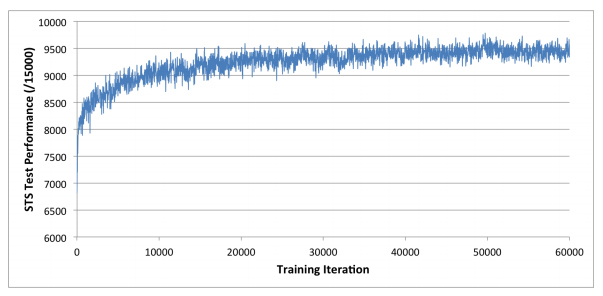

Having trained Giraffe, the final step is to test it and here the results make for interesting reading. Lai tested his machine on a standard database called the Strategic Test Suite, which consists of 1,500 positions that are chosen to test an engine’s ability to recognize different strategic ideas. “For example, one theme tests the understanding of control of open files, another tests the understanding of how bishop and knight’s values change relative to each other in different situations, and yet another tests the understanding of center control,” he says.

The results of this test are scored out of 15,000.

Lai uses this to test the machine at various stages during its training. As the bootstrapping process begins, Giraffe quickly reaches a score of 6,000 and eventually peaks at 9,700 after only 72 hours. Lai says that matches the best chess engines in the world.

“[That] is remarkable because their evaluation functions are all carefully hand-designed behemoths with hundreds of parameters that have been tuned both manually and automatically over several years, and many of them have been worked on by human grandmasters,” he adds.

Lai goes on to use the same kind of machine learning approach to determine the probability that a given move is likely to be worth pursuing. That’s important because it prevents unnecessary searches down unprofitable branches of the tree and dramatically improves computational efficiency.

Lai says this probabilistic approach predicts the best move 46 percent of the time and places the best move in its top three ranking, 70 percent of the time. So the computer doesn’t have to bother with the other moves.

That’s interesting work that represents a major change in the way chess engines work. It is not perfect, of course. One disadvantage of Giraffe is that neural networks are much slower than other types of data processing. Lai says Giraffe takes about 10 times longer than a conventional chess engine to search the same number of positions.

But even with this disadvantage, it is competitive. “Giraffe is able to play at the level of an FIDE International Master on a modern mainstream PC,” says Lai. By comparison, the top engines play at super-Grandmaster level.

That’s still impressive. “Unlike most chess engines in existence today, Giraffe derives its playing strength not from being able to see very far ahead, but from being able to evaluate tricky positions accurately, and understanding complicated positional concepts that are intuitive to humans, but have been elusive to chess engines for a long time,” says Lai. “This is especially important in the opening and end game phases, where it plays exceptionally well.”

And this is only the start. Lai says it should be straightforward to apply the same approach to other games. One that stands out is the traditional Chinese game of Go, where humans still hold an impressive advantage over their silicon competitors. Perhaps Lai could have a crack at that next.

http://www.technologyreview.com/view/541276/deep-learning-machine-teaches-itself-chess-in-72-hours-plays-at-international-master/

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the It’s Interesting community.