High school students in 1960 take the Project Talent test, the largest survey of American teenagers ever done; it is now being used for research into dementia. (American Institutes for Research)

By Tara Bahrampour

In 1960, Joan Levin, 15, took a test that turned out to be the largest survey of American teenagers ever conducted. It took two-and-a-half days to administer and included 440,000 students from 1,353 public, private and parochial high schools across the country — including Parkville Senior High School in Parkville, Md., where she was a student.

“We knew at the time that they were going to follow up for a long time,” Levin said — but she thought that meant about 20 years.

Fifty-eight years later, the answers she and her peers gave are still being used by researchers — most recently in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease. A study released this month found that subjects who did well on test questions as teenagers had a lower incidence of Alzheimer’s and related dementias in their 60s and 70s than those who scored poorly.

Known as Project Talent, the test was funded by the U.S. government, which had been concerned, given the Soviet Union’s then-recent successful Sputnik launch, that Americans were falling behind in the space race.

Students answered questions about academics and general knowledge, as well as their home lives, health, aspirations and personality traits. The test was intended to identify students with aptitudes for science and engineering. Test-takers included future rock stars Janis Joplin, then a senior at Thomas Jefferson High School in Port Arthur, Tex., and Jim Morrison, then a junior at George Washington High School in Alexandria, Va.

In recent years, researchers have used Project Talent data for follow-up studies, including one published Sept. 7 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Conducted by researchers at the Washington-based American Institutes for Research (AIR), the organization that originally administered the test, it compared results for more than 85,000 test-takers with their 2012-2013 Medicare claims and expenditures data, and found that warning signs for dementia may be discernible as early as adolescence.

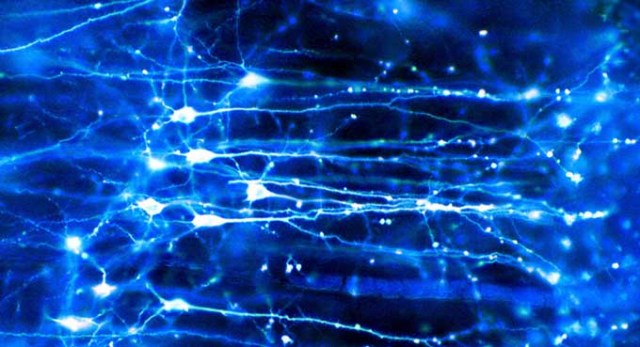

The study looked at how students scored on 17 areas of cognitive ability such as language, abstract reasoning, math, clerical skills, and visual and spatial prowess, and found that people with lower scores as teenagers were more prone to getting Alzheimer’s and related dementias in their 60s and early 70s.

Specifically, those with lower mechanical reasoning and memory for words as teens had a higher likelihood of developing dementia in later life: Men in the lower-scoring half were 17 percent more likely, while women with lower scores were 16 percent more likely. Worse performance on other components of the test also increased the risk for later-life dementia.

An estimated 5.7 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease, and in the absence of scientific breakthroughs to curb the disease, the Alzheimer’s Association projects that number could reach 14 million by 2050, with the cost of care topping $1 trillion per year.

The 1960 test could have the potential to be like the groundbreaking Framingham study, a decades-long study of men in Massachusetts that led to reductions in heart disease in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, said Susan Lapham, director of Project Talent and a co-author of the JAMA study.

“If Project Talent can be for dementia what the Framingham study was for heart disease, it will make a difference in public health,” she said. “It indicates that we should be designing interventions for kids in high school and maybe even earlier to maybe keep their brains active from a young age.”

This might include testing children, identifying those with lower scores and “getting them into a program to make sure they’re not missing out and maybe putting themselves at risk,” she said.

For years, little was done with the Project Talent data because the participants could not be found. A proposal in the 1980s to try to find them failed because, in that pre-Internet age, the task seemed too daunting.

In 2009, as the students’ 50th high school reunions were coming up, researchers decided to use the gatherings as an occasion to contact many of them. (About a quarter have died.) They were then able to use the test data to study things such as the effects of diabetes and personality type on later-life health.

But when contacted, the participants were most interested in dementia, Lapham said. “They wanted that to be studied more than any other topic,” she said. “They said, ‘The thing I fear most is dementia.’ ”

While students were supposed to have received their results soon after taking the test, some students said they did not remember getting them.

Receiving her results recently was interesting in hindsight, said Levin, a retired human-resources director who is now 73 and living in Cockeysville, Md. Most of her scores were over 75 percent, with very high marks in vocabulary, abstract reasoning and verbal memory, and lower marks in table reading and clerical tasks.

Low scores do not mean a person will get dementia; the correlation is merely associated with a higher risk. But even if her scores had been lower, Levin said she would want to know. “I’m kind of a planner, and I look ahead,” she said. “I’d want my daughter and her family to maybe have an idea of what to expect.”

Karen Altpeter, 75, of Prescott, Wis., said she would also probably want to know about her risk, because her mother and grandmother had Alzheimer’s. She liked the idea that the answers she had given as a teen could help science.

“If there’s any opportunity I can have to make a difference just by taking a test and answering some questions, I’ll do it,” she said. “I want the opportunity to make things better for people.”

Earlier studies had suggested a relationship between cognitive abilities in youth and dementia in later life, including one that followed 800 nuns earlier in the 20th century and found that the complexity of sentences they used in writing personal essays at 21 correlated with their dementia risk in old age.

But that study included only women and no minorities. Project Talent’s subjects reflected the nation’s demographic mix in 1960.

Today, however, the country is more diverse. The number of minorities 65 and older is projected to grow faster than the general population, and by 2060 there will be about 3.2 million Hispanics and 2.2 million African Americans with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, according to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published this week. African Americans and Hispanics have a higher prevalence of Alzheimer’s and related diseases than non-Hispanic whites.

A follow-up study underway of a smaller sample of the Project Talent pool — 22,500 people — will be weighted to reflect today’s population mix and will dig more deeply into age-related brain and cognitive changes over time.

It will examine the long-term impact of school quality and school segregation on brain health, and the impact of adolescent socioeconomic disadvantage on cognitive and psychosocial resilience, with a special focus on the experiences of participants of color.

That study includes an on-paper survey of demographics, family and marriage history, residential history, educational attainment and health status; an online survey of health, mental health and quality of life; and a detailed cognitive assessment by phone of things such as memory for words and counting backward.

Researchers will also evaluate school quality to determine whether there are racial or ethnic differences in the benefits of attending higher quality schools, and explore more deeply why some people develop dementia and some do not.

The follow-up, slated to be completed next year, is funded by the National Institute on Aging, part of the National Institutes of Health, and conducted by AIR in conjunction with researchers from Columbia University Medical Center and the University of Southern California.

Cliff Jacobs, 75, of Arlington, Va., who took the Project Talent test as a high school junior in Tenafly, N.J., doesn’t remember hearing about any results. Then, a few months ago, researchers conducting the follow-up study contacted him, tested his cognitive abilities and asked about his life history.

“They delved into my issues growing up — did my parents smoke, and was I exposed to any secondhand smoke? Yeah, my parents both smoked, and I didn’t even think it was something to consider,” he said.

A retired geoscientist for the National Science Foundation, Jacobs said he would be interested in learning if he is at risk for dementia.

“The statistical correlation is not one that will necessarily apply to you, but they can give you some probabilities,” he said. “I guess basic human nature would be, ‘Yeah, you’d probably want to know.’ ”

Try these 12 sample questions from the test.

Can’t see the Quiz? Click Here.

1

In the Bible story, Samson knew he would lose his strength if

his hair were cut.

he fell in love.

he left Jerusalem.

he spoke with a Philistine.

he went to war.

2

Chartreuse is a mixture of

green and blue.

yellow and orange.

yellow and green.

orange and brown.

red and orange.

3

The above is usually called a

fly.

spoon.

spinner.

plug.

streamer.

4

High pointed arches are used chiefly in

Roman architecture.

Greek architecture.

Gothic architecture.

Renaissance architecture.

modern architecture.

5

If a camper sees a garter snake, he should

leave it alone.

pin its head down with a forked stick.

hit it with a rock.

climb the nearest tree.

stand still until it leaves.

6

Tartar sauce is most often served with

tossed salad.

ice cream.

fish.

barbecued beef.

chow mein.

7

Suppose that after the post office is closed, someone finds he urgently needs stamps. He should probably try getting them

in a drug store.

from a stamp collector.

by phoning the postmaster’s home.

in a department store.

in a gas station.

8

In a suspension bridge, the road bed is supported by

pontoons.

pilings.

arches.

cables.

cantilevers.

9

Which of these guns has the largest bore?

12 ga.

.22 cal.

.44 cal.

16 ga.

20 ga.

10

A boy takes a girl to a movie and they find a pair of seats on a side aisle. Usually the girl should take the seat

on the left.

on the right.

nearest the aisle.

furthest from the aisle.

nearest the center of the theater.

11

About when did Leonardo de Vinci live?

1st century

5th century

10th century

15th century

20th century

12

Locks were built into the Panama Canal because

the Atlantic Ocean is higher than the Pacific.

the Pacific Ocean is higher than the Atlantic.

Panama is above sea level.

the canal is narrow.

the canal is wide.