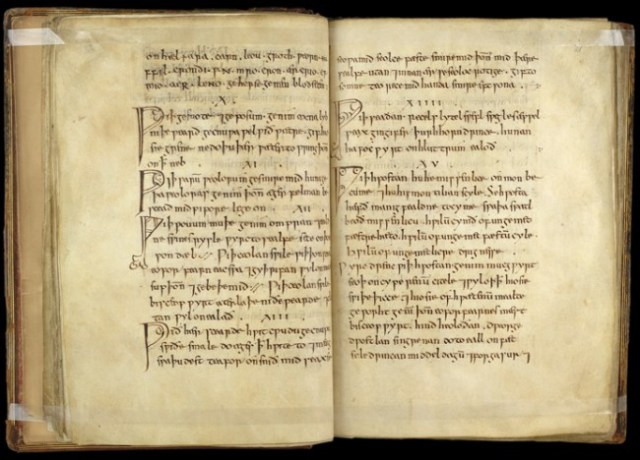

Donald Cooper with scientific colleagues.

Donald Cooper mug shot.

A former University of Colorado professor has been arrested on suspicion of creating a company to sell marked-up lab equipment to the Boulder campus in what prosecutors call a theft “scheme.”

Donald Cooper, 44, was arrested at his home in Boulder on Tuesday afternoon, according to Boulder County District Attorney’s Office officials. It was unclear late Tuesday if Cooper had posted bond, which was set at $5,000.

He is facing a felony charge of theft between $20,000 and $100,000. Prosecutors allege that he created Boulder Science Resource to buy lasers and other lab equipment that he marked up 300 percent and then resold to his university laboratory, according to an arrest affidavit.

The arrangement also benefitted the professor’s father, who received a salary and a car from Boulder Science Resource, according to the arrest affidavit.

In total, CU paid Boulder Science Resource $97,554.03 between Jan. 1, 2009, and April 30, 2013, according to the affidavit.

According to CU’s calculations, Cooper’s markups cost the university $65,036.

Cooper resigned in July 2014 as part of a settlement deal with the university, which had begun the process of firing him on suspicion of fiscal misconduct. He had been director of the molecular neurogenetics and optophysiology laboratory in CU’s Institute for Behavioral Genetics, where he was a tenured associate professor.

After he learned about the university’s internal investigation, Cooper filed a notice of claim in September 2013 seeking $20 million in damages. Any person who wishes to sue a state entity must first file a notice of claim.

Cooper’s attorney Seth Benezra wrote in the notice of claim that Gary Cooper, the professor’s father, was the sole owner of Boulder Science Resource. He also wrote that the company sold CU equipment “at prices that were greatly discounted.”

Donald Cooper also complained that CU investigators had obtained an email about his father’s “alleged mental impairment,” according to the notice of claim.

“(The investigator’s) theory is that Gary Cooper lacks the mental capacity to run (Boulder Science Resource) and so Dr. Cooper must really be in charge,” Benezra wrote. “This assertion was pure speculation based on entirely private information and was rebutted by Dr. Cooper in multiple meetings with investigators.”

Benezra did not return messages from the Daily Camera on Tuesday. It’s unclear who is representing Cooper in the criminal case.

Though Cooper claims that his father was in charge of the company, prosecutors assert that the professor “employed a scheme” to deceive the university for his own gain, according to the affidavit.

“It is alleged that (Boulder Science Resource) was created to defraud the University of Colorado Boulder by acting as a middleman to generate income to employ Gary and to provide personal benefit for Cooper,” wrote Alisha Baurer, an investigator in the District Attorney’s Office.

‘Fake business’

CU was tipped off about Boulder Science Resource by another employee in Cooper’s department, who told investigators that he heard about the arrangement from Cooper’s ex-wife, according to the arrest affidavit.

The ex-wife told the CU employee that Cooper had created a “fake business” using “dirty money” from grants and start-up funds, according to the affidavit.

The financial manager for Cooper’s department told investigators that he never mentioned that his dad owned Boulder Science Resource, and said Cooper only referred to “Gary” by his first name, according to the affidavit.

The DA’s Office determined that Gary Cooper received $23,785.80 from Boulder Science Resource in the form of a salary and a car. They also found that $31,974.89 was paid from the company’s accounts to Donald Cooper’s personal credit card and that $14,733.54 was paid to his personal PayPal account from the business, according to the affidavit.

CU’s internal audit found that Boulder Science Resource had no customers other than the university and Mobile Assay, a company founded by Donald Cooper based on a technology he developed at the university.

Some of the money CU paid to Boulder Science Resource came from federal grants, including $7,220 from the National Institutes of Health and $15,288 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, according to the internal audit report.

CU’s investigation found that although Cooper claimed his father purchased the lab equipment for Boulder Science Resource, the professor used his university email account to negotiate with the manufacturers.

“It is internal audit’s conclusion that the forgoing acts/failures to act were done with intent to gain an unauthorized benefit,” according to the audit report.

Boulder Science Resource was dissolved in December 2013, according to the Secretary of State’s Office.

Settlement terms

Reached by phone Tuesday afternoon, Patrick O’Rourke, CU’s chief legal officer, said the university was aware of Cooper’s arrest and will cooperate with prosecutors.

CU settled with Cooper last summer after initiating termination proceedings. In exchange for his resignation, the university agreed to provide the professor with a letter of reference “acknowledging his significant achievement in creating a neuroscience undergraduate program,” according to the settlement document.

CU also paid $20,000 to partially reimburse Cooper’s attorney and forgave an $80,000 home loan. CU provides down payment-assistance loans to some faculty members.

Had the university continued the termination process, which is lengthy, Cooper would have continued to receive his full salary of $89,743 and all benefits during the proceedings.

O’Rourke said the university instead opted to accept Cooper’s resignation and saved money with the settlement.

http://www.dailycamera.com/cu-news/ci_28056525/former-cu-boulder-professor-arrested-theft-case