Results imply creative people are 25% more likely to carry genes that raise risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. But others argue the evidence is flimsy.

The ancient Greeks were first to make the point. Shakespeare raised the prospect too. But Lord Byron was, perhaps, the most direct of them all: “We of the craft are all crazy,” he told the Countess of Blessington, casting a wary eye over his fellow poets.

The notion of the tortured artist is a stubborn meme. Creativity, it states, is fuelled by the demons that artists wrestle in their darkest hours. The idea is fanciful to many scientists. But a new study claims the link may be well-founded after all, and written into the twisted molecules of our DNA.

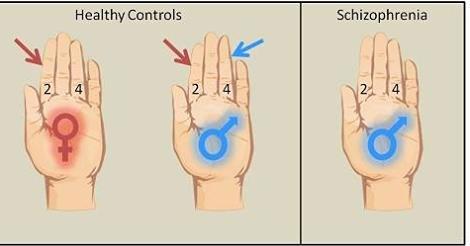

In a large study published on Monday, scientists in Iceland report that genetic factors that raise the risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are found more often in people in creative professions. Painters, musicians, writers and dancers were, on average, 25% more likely to carry the gene variants than professions the scientists judged to be less creative, among which were farmers, manual labourers and salespeople.

Kari Stefansson, founder and CEO of deCODE, a genetics company based in Reykjavik, said the findings, described in the journal Nature Neuroscience, point to a common biology for some mental disorders and creativity. “To be creative, you have to think differently,” he told the Guardian. “And when we are different, we have a tendency to be labelled strange, crazy and even insane.”

The scientists drew on genetic and medical information from 86,000 Icelanders to find genetic variants that doubled the average risk of schizophrenia, and raised the risk of bipolar disorder by more than a third. When they looked at how common these variants were in members of national arts societies, they found a 17% increase compared with non-members.

The researchers went on to check their findings in large medical databases held in the Netherlands and Sweden. Among these 35,000 people, those deemed to be creative (by profession or through answers to a questionnaire) were nearly 25% more likely to carry the mental disorder variants.

Stefansson believes that scores of genes increase the risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. These may alter the ways in which many people think, but in most people do nothing very harmful. But for 1% of the population, genetic factors, life experiences and other influences can culminate in problems, and a diagnosis of mental illness.

“Often, when people are creating something new, they end up straddling between sanity and insanity,” said Stefansson. “I think these results support the old concept of the mad genius. Creativity is a quality that has given us Mozart, Bach, Van Gogh. It’s a quality that is very important for our society. But it comes at a risk to the individual, and 1% of the population pays the price for it.”

Stefansson concedes that his study found only a weak link between the genetic variants for mental illness and creativity. And it is this that other scientists pick up on. The genetic factors that raise the risk of mental problems explained only about 0.25% of the variation in peoples’ artistic ability, the study found. David Cutler, a geneticist at Emory University in Atlanta, puts that number in perspective: “If the distance between me, the least artistic person you are going to meet, and an actual artist is one mile, these variants appear to collectively explain 13 feet of the distance,” he said.

Most of the artist’s creative flair, then, is down to different genetic factors, or to other influences altogether, such as life experiences, that set them on their creative journey.

For Stefansson, even a small overlap between the biology of mental illness and creativity is fascinating. “It means that a lot of the good things we get in life, through creativity, come at a price. It tells me that when it comes to our biology, we have to understand that everything is in some way good and in some way bad,” he said.

But Albert Rothenberg, professor of psychiatry at Harvard University is not convinced. He believes that there is no good evidence for a link between mental illness and creativity. “It’s the romantic notion of the 19th century, that the artist is the struggler, aberrant from society, and wrestling with inner demons,” he said. “But take Van Gogh. He just happened to be mentally ill as well as creative. For me, the reverse is more interesting: creative people are generally not mentally ill, but they use thought processes that are of course creative and different.”

If Van Gogh’s illness was a blessing, the artist certainly failed to see it that way. In one of his last letters, he voiced his dismay at the disorder he fought for so much of his life: “Oh, if I could have worked without this accursed disease – what things I might have done.”

In 2014, Rothernberg published a book, “Flight of Wonder: an investigation of scientific creativity”, in which he interviewed 45 science Nobel laureates about their creative strategies. He found no evidence of mental illness in any of them. He suspects that studies which find links between creativity and mental illness might be picking up on something rather different.

“The problem is that the criteria for being creative is never anything very creative. Belonging to an artistic society, or working in art or literature, does not prove a person is creative. But the fact is that many people who have mental illness do try to work in jobs that have to do with art and literature, not because they are good at it, but because they’re attracted to it. And that can skew the data,” he said. “Nearly all mental hospitals use art therapy, and so when patients come out, many are attracted to artistic positions and artistic pursuits.”

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jun/08/new-study-claims-to-find-genetic-link-between-creativity-and-mental-illness