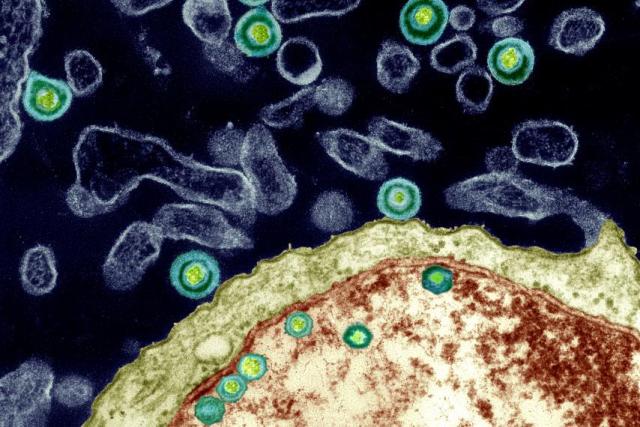

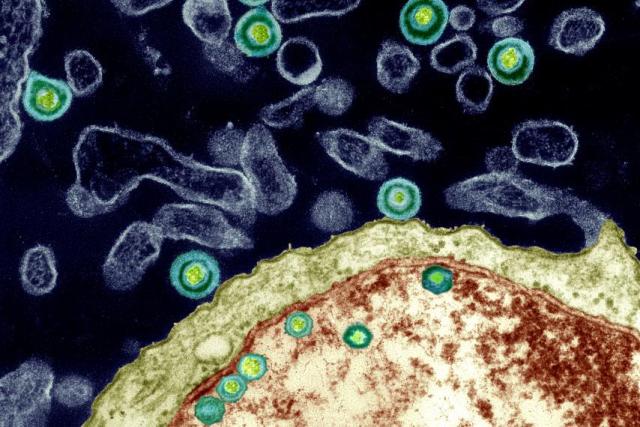

Herpes simplex viruses pass through the outer protein coat of a nucleus, magnified 40,000 times. Dr. Ruth Itzhak’s research published in 1997 revealed a potential link to the presence of HSV-1 (one specific variety of Herpes simplex) and the onset of Alzheimer’s in 60 percent of the cases they studied. However, she has only been able to study a low number of cases since the work has received only a cursory nod from the greater research world and little funding.

By Ed Cara

As recently as the 1970s, doctors stubbornly treated complaints of festering open sores in the stomach as a failing of diet or an inability to manage stress. Though we had long accepted the basic premise of Louis Pasteur’s germ theory—that flittering short bursts of disease and death are often caused by microscopic beings that could be stopped by sanitary food, water and specially crafted drugs—many researchers ardently resisted the idea that they could also trigger more complicated, chronic illnesses.

When it came to ulcers, no one believed that any microorganisms could endure in the acidic cauldron of our digestive system. It took the gumshoe work of Australian doctors and medical researchers Barry Marshall and Robin Warren in the 1980s to debunk that belief and discover the specific bug responsible for most chronic stomach ulcers, Helicobacter pylori. Marshall even went so far as to swallow the germ to prove the link was real and, obviously, became sick soon after. Thankfully, his self-sacrifice was eventually validated when he and Warren were awarded a Nobel Prize in 2005.

But while modern medicine has grown comfortable with the idea that even chronic physical ailments can be sparked by the living infinitesimal, there is an even bolder, more controversial proposition from a growing number of researchers. It’s the idea that certain germs, bugs and microbes can lie hidden in the body for decades, all the while slowly damaging our brains, even to the point of dementia, depression and schizophrenia.

In January 2016, a team led by Shawn Gale, an associate professor in psychology at Brigham Young University, looked at the infection history of 5,662 young to middle-aged adults alongside the results of tests intended to measure cognition. Gale’s rogues’ gallery included both parasites (the roundworm and Toxoplasma gondii ) and viruses (the hepatitis clan, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus Types 1 and 2). The team created an index of infectious disease —the more bugs a participant had been exposed to, the higher the person’s index score. It turned out that those with a higher score were more likely to have worse learning and memory skills, as well as slower information-processing speed than those with a lower score, even after controlling for other factors, like age, sex and financial status.

Aside from their shared ability to stay rooted inside us, the ways these pathogens might influence our noggins are as varied as their biology is from one another. Some, like T. gondii (often transmitted to humans via contaminated cats and infected dirt), can discreetly infest the brain and cause subtle changes to our brain chemistry, altering levels of neurotransmitters like dopamine while causing no overt signs of disease. Others, like hepatitis C, are suspected of hitching a ride onto infected white blood cells that cross the brain-blood barrier and, once inside, deplete our supply of white brain matter, the myelin-coated axons that help neurons communicate with each other and seem to actively shape how we learn. And still others, like H. pylori, could trigger a low-level but chronic inflammatory response that gradually wears down our body and mind alike.

Gale’s team found only fairly small deficits in cognition connected to infection. But other researchers, like Ruth Itzhaki, professor emeritus of molecular neurobiology at Britain’s University of Manchester, believe microbes may play an outsized role in one of the most devastating neurodegenerative disorders around: Alzheimer’s disease, which afflicted 47 million people worldwide in 2015. Last March, Itzhaki and a globe-spanning group of researchers penned an editorial in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, imploring the scientific community to more seriously pursue a proposed link between Alzheimer’s and particular germs, namely herpes simplex virus Type 1 (HSV-1), Chlamydia pneumoniae and spirochetes—a diverse group of bacteria that include those responsible for syphilis and Lyme disease. The unusually direct plea, for scientists at least, was the culmination of decades of frustration.

“There’s great hostility to the microbial concept amongst certain influential people in the field, and they are the ones who usually determine whether or not one’s research grant application is successful,” says Itzhaki. “The irony is that they never provide scientific objections to the concepts—they just belittle them, so there’s nothing to rebut!”

It’s a frustration Itzhaki knows too well; in 1991, her lab published the first paper finding a clear HSV-1 link to Alzheimer’s. Since then, according to Itzhaki, over 100 published studies, from her lab and elsewhere, have been supportive of the same link. Nevertheless, Itzhaki says, the work has received only a cursory nod from the greater research world and little funding. Out of the $589 million allocated to Alzheimer’s research by the National Institutes of Health in 2015, exactly zero appeared to be spent on studying the proposed HSV-1 connection.

HSV-1 is more often known as the version of herpes that causes cold sores. Nearly all of us carry the virus from infancy; our peripheral nervous system serves as its dormant nesting ground. From there, HSV-1 can reactivate and occasionally cause mild flare-ups of disease, typically when our immune system is overwhelmed due to stress or other infections. Itzhaki’s lab, however, found that by the time we reach our golden years, the virus often migrates to the brain, where it remains capable of resurrecting itself and wreaking a new sort of havoc when opportunity presents, such as when our immune system wavers in old age.

Her team has also discovered the presence of HSV-1 in the telltale plaques—clumps of proteins in the nerve cells of the brain—used to diagnose Alzheimer’s. In mice and cell cultures infected with HSV-1, they’ve found accumulation of two proteins, beta-amyloid and tau, that form the main components of, respectively, plaques and tangles—twisted protein fibers that form inside dying cells and are another defining characteristic of Alzheimer’s. Plaques and tangles, while sometimes found in normal aging brains, have been found to overflow in the brains of deceased Alzheimer’s sufferers; neuroscientists believe these protein accumulations can cause neuron death and tissue loss. Itzhaki speculates that herpes-infected cells may either produce the proteins in an attempt to fend off HSV-1 or, because the virus itself commands them to, the proteins somehow needed to jump-start the virus’s replication.

Itzhaki, Gale and their colleagues emphasize that rather than being the sole cause of memory loss, slower reaction time or depression, viral and bacterial infections are likely just one ingredient in a soup of risk factors. But for Alzheimer’s, HSV-1 could be especially significant. Itzhaki has found that elderly people who carried both HSV-1 in the brain and the e-4 subtype of the APOE gene (responsible for creating a protein that helps transport cholesterol throughout the body) were 12 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s than people without either.

APOE-e4, already considered a significant risk factor for Alzheimer’s and thought to make us more vulnerable to viral infection, has also been linked to a greater risk of dementia in HIV-infected patients. In a 1997 Lancet paper, Itzhaki’s group concluded that HSV-1 infection, in conjunction with APOE-e4, could account for about 60 percent of the Alzheimer’s cases they studied. Due to limited funds, however, her group was able to study only a relatively low number of cases.

“I think the proposed theory is certainly reasonable given the supporting evidence,” says Iain Campbell, a professor of molecular biology at the University of Sydney. “What is difficult to establish here is actual causality.”

It might be the case that HSV-1 and other suspects aren’t responsible for the emergence of Alzheimer’s but are simply given free rein to worsen its symptoms as the neurodegenerative disorder weakens both the immune and nervous systems. Deciphering the relationship between these latent infections and Alzheimer’s will take more dedicated research, an effort that Itzhaki feels has been stymied by the persistent lack of resources available to her and her like-minded colleagues.

As things stand, though, she believes there is enough evidence to go ahead with treatment trials; for instance, giving Alzheimer’s patients HSV-1-targeted antivirals in hopes of slowing down or stopping the progression of the disease. She and a team of clinicians are trying to obtain a grant for such a pilot clinical trial to do just that.

Exasperated as Itzhaki has been, the headwinds against her and those who share her beliefs about the brain are slowly dying down. In some cases, once-derided and obscure scientists studying how infections affect the brain are now getting some financial support. There’s Jaroslav Flegr, for example, who has for decades theorized that T. gondii could alter human behavior and even cause certain forms of schizophrenia. In the wake of increased media attention, Flegr’s volume of work on T. gondii has noticeably stepped up as well. From 2014 to 2015, he co-authored 13 papers on T. gondii, nearly twice the number he published the previous two years; the trend of increased T. gondii papers holds across all of PubMed, the largest database of published biomedical research available. “ I have no serious problem with funding of my Toxo research now,” Flegr says.

As of now, though, there have been no ulcer-related Sherlock moments to prove a link between mental dysfunction and latent infections—only indirect correlations clumping together to form a blurry snapshot of a potential crime scene. Which is why Gale and others recommend a wait-and-see approach for the public, even as they acknowledge the potentially vast implications of their research. “I wouldn’t want someone to go out tomorrow and get a whole battery of tests,” he says. “There’s still a lot we need to understand.”

http://www.newsweek.com/viral-bacterial-links-brains-decline-462194