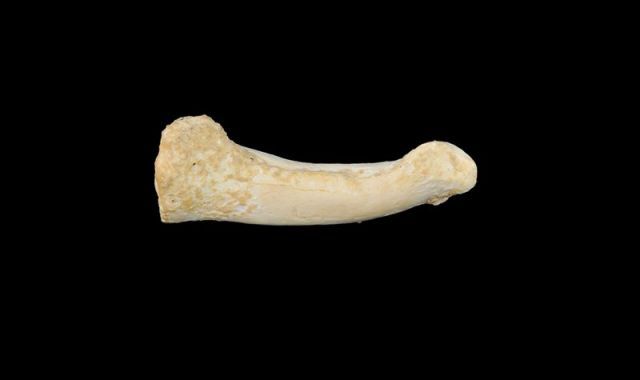

Remains from Callao Cave in the Philippines, including a foot bone, belong to a new hominin species, Homo luzonensis.Credit: Rob Rownd, UP-ASP Film Inst.

The human family tree has grown another branch, after researchers unearthed remains of a previously unknown hominin species from a cave in the Philippines. They have named the new species, which was probably small-bodied, Homo luzonensis.

The discovery, reported in Nature on 10 April1, is likely to reignite debates over when ancient human relatives first left Africa. And the age of the remains — possibly as young as 50,000 years old — suggests that several different human species once co-existed across southeast Asia.

The first traces of the new species turned up more than a decade ago, when researchers reported the discovery of a foot bone dating to at least 67,000 years old in Callao Cave on the island of Luzon, in the Philippines2. The researchers were unsure which species the bone was from, but they reported that it resembled that of a small Homo sapiens.

Further excavations of Callao Cave uncovered a thigh bone, seven teeth, two foot bones and two hand bones — with features unlike those of other human relatives, contends the team, co-led by Florent Détroit, a palaeoanthropologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. The remains come from at least two adults and one child.

“Together, they create a strong argument that this is something new,” says Matthew Tocheri, a palaeoanthropologist at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Canada.

Hominin history

H. luzonensis is the second new human species to be identified in southeast Asia in recent years. In 2004, another group announced the discovery3 of Homo floresiensis — also known as the Hobbit — a species that would have stood just over a metre in height, on the Indonesian island of Flores.

But Détroit and his colleagues argue that the Callao Cave remains are distinct from those of H. floresiensis and other hominins — including a species called Homo erectus thought to have been the first human relative to leave Africa, some 2 million years ago.

Seven hominin teeth, including molars and premolars, were found in Callao Cave.Credit: Callao Cave Archaeology Project

The newly discovered molars are extremely small compared with those of other ancient human relatives. Elevated cusps on the molars, like those in H. sapiens, are not as pronounced as they were in earlier hominins. The shape of the internal molar enamel looks similar to that of both H. sapiens and H. erectus specimens found in Asia. The premolars discovered at Callao Cave are small but still in the range of those of H. sapiens and H. floresiensis. But the authors report that the overall size of the teeth, as well as the ratio between molar and premolar size, is distinct from those of other members of the genus Homo.

The shape of the H. luzonensis foot bones is also distinct. They most resemble those of Australopithecus — primitive hominins, including the famous fossil Lucy, thought not to have ever left Africa. Curves in the toe bones and a finger bone of H. luzonensis suggest that the species might have been adept at climbing trees.

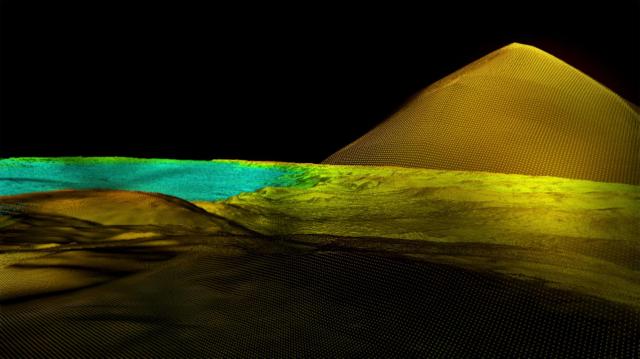

Curves in the toe bones of H. luzonensis may have been adaptations for climbing.Credit: Callao Cave Archaeology Project

The researchers are cautious about estimating H. luzonensis’ height, because there are only a few remains to go on. But given its small teeth, and the foot bone reported in 2010, Détroit thinks that its body size was within the range of small H. sapiens, such as members of some Indigenous ethnic groups living on Luzon and elsewhere in the Philippines today, sometimes known collectively as the Philippine Negritos. Men from these groups living in Luzon have a recorded mean height of around 151 centimetres and the women about 142 centimetres.

The right fit

Researchers are split on how H. luzonensis fits into the human family tree. Détroit favours the view that the new species descends from a H. erectus group whose bodies gradually evolved into forms different from those of their ancestors.

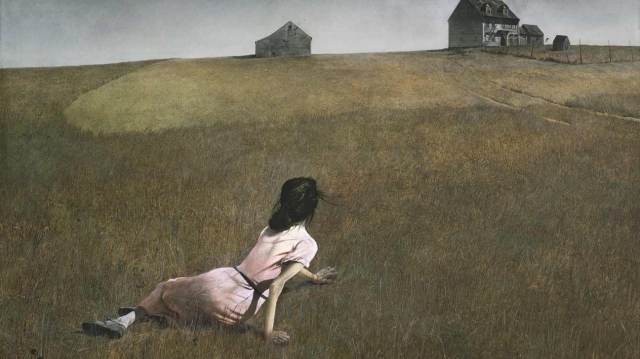

“You get different evolutionary pathways on islands,” says palaeontologist Gerrit van den Bergh at the University of Wollongong in Australia. “We can imagine H. erectus arrives on islands like Luzon or Flores, and no longer needs to engage in endurance running but needs to adapt to spend the night in trees.”

But, given the species’ similarities to Australopithecus, Tocheri wonders whether the Callao Cave dwellers descended from a line that migrated out of Africa before H. erectus.

Genetic material from the remains could help scientists to identify the species’ relationship to other hominins, but efforts to extract DNA from H. luzonensis have failed so far. However, the bones and teeth were dated to at least 50,000 years old. This suggests that the species might have been roaming southeast Asia at the same time as H. sapiens, H. floresiensis and a mysterious group known as the Denisovans, whose DNA has been found in contemporary humans in southeast Asia.

“Island southeast Asia appears to be full of palaeontological surprises that complicate simple scenarios of human evolution,” says William Jungers, a palaeoanthropologist at Stony Brook University in New York.