by Jason Daley

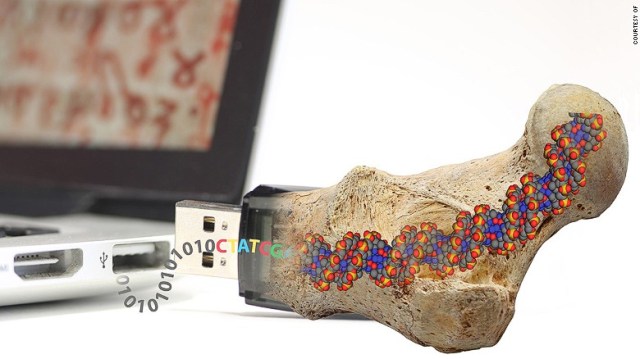

Fiinding bones from early humans and their ancestors is difficult and rare—often requiring scientists to sort through the sediment floor of caves in far-flung locations. But modern advances in technology could completely transform the field. As Gina Kolta reports for The New York Times, a new study documents a method to extract and sequence fragments of hominid DNA from samples of cave dirt.

The study, published this week in the journal Science, could completely change the type of evidence available to study our ancestral past. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, collected 85 sediment samples from seven archeological sites in Belgium, Croatia, France, Russia and Spain, covering a span of time from 550,000 to 14,000 years ago.

As Lizzie Wade at Science reports, when the team first sequenced the DNA from the sediments, they were overwhelmed. There are trillions of fragments of DNA in a teaspoon of dirt, mostly material from other mammals, including woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceroses, cave bears and cave hyenas. To cut through the clutter and examine only hominid DNA, they created a molecular “hook” made from the mitochondrial DNA of modern humans. The hook was able to capture DNA fragments that most resembled itself, pulling out fragments from Neanderthals at four sites, including in sediment layers where bones or tools from the species were not present. They also found more DNA from Denisovans, an enigmatic human ancestor found only in single cave in Russia.

“It’s a great breakthrough,” Chris Stringer, anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London tells Wade. “Anyone who’s digging cave sites from the Pleistocene now should put [screening sediments for human DNA] on their list of things that they must do.”

So how did the DNA get there? The researchers can’t say exactly, but it wouldn’t be too difficult. Humans shed DNA constantly. Any traces of urine, feces, spit, sweat, blood or hair would all contain minute bits of DNA. These compounds actually bind with minerals in bone, and likely did the same with minerals in the soil, preserving it, reports Charles Q. Choi at LiveScience.

There’s another—slightly scarier—option for the DNA’s origins. The researchers found a lot of hyena DNA at the study sites, Matthias Meyer, an author of the study tells Choi. “Maybe the hyenas were eating human corpses outside the caves, and went into the caves and left feces there, and maybe entrapped in the hyena feces was human DNA.”

The idea of pulling ancient DNA out of sediments is not new. As Kolta reports, researchers have previously successfully recovered DNA fragments of prehistoric mammals from a cave in Colorado. But having a technique aimed at finding DNA from humans and human ancestors could revolutionize the field. Wade points out that such a technique might have helped produce evidence for the claim earlier this week that hominids were in North America 130,000 years ago.

DNA analysis of sediments might eventually become a routine part of archeology, similar to radio carbon dating, says Svante Pääbo, director of the Evolutionary Genetics department at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in the press release. The technique could also allow researchers to start searching for traces of early hominids at sites outside of caves.

“If it worked, it would provide a much richer picture of the geographic distribution and migration patterns of ancient humans, one that was not limited by the small number of bones that have been found,” David Reich, Harvard geneticist tells Kolta. “That would be a magical thing to do.”

As Wade reports, the technique could also solve many mysteries, including determining whether certain tools and sites were created by humans or Neanderthals. It could also reveal even more hominid species that we have not found bones for, creating an even more complete human family tree.