by Mike McRae

Earth might have a dizzying array of life forms, but our biology ultimately remains a solitary data point – we simply don’t have a reference for life based on DNA different from our own. Now, scientists have taken matters into their hands to push the boundaries on what life could be like.

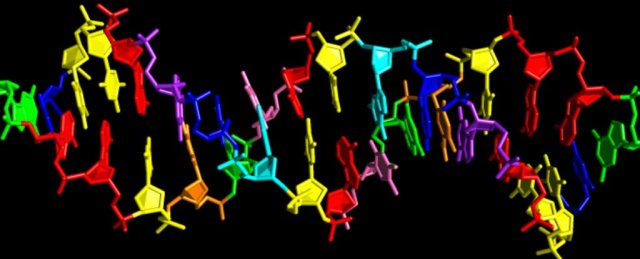

Research funded by NASA and led by the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in the US has led to the creation of an entirely new flavour of the DNA double helix, one that has an additional four nucleotide bases.

It’s being called hachimoji DNA (from the Japanese words for ‘eight letters’) and it includes two new pairs to add to the existing partnerships of adenine (A) paired with thymine (T), and guanine (G) with cytosine (C).

This work to expand on nature’s own genetic recipe might sound a little familiar. The same scientists already successfully squeezed in two new letters in 2011. Only last year yet another version of an extended alphabet, also with six letters, was made to function inside a living organism.

Now, in what might seem like a case of overachievement, researchers have gone back to the drawing board to develop even more non-standard nucleotides.

They have a purpose for doubling the number of codes in the recipe book, though.

“By carefully analysing the roles of shape, size and structure in hachimoji DNA, this work expands our understanding of the types of molecules that might store information in extraterrestrial life on alien worlds,” says chemist Steven Benner.

We already know a lot about the stability and functionality of ‘natural’ DNA under a range of environmental conditions, and are slowly teasing apart possible scenarios describing its evolution from simpler organic materials to living chemistry.

But to really get a good sense of how a genetic system could evolve, we need to test the limits of its underlying chemistry.

Hachimoji DNA certainly allows for that. The new codes, labelled P, B, Z and S, are based on the same kind of nitrogenous molecules as existing ones, categorised as purines and pyrimidines.

Similarly, they link up with hydrogen bonds to form their own base pairs – S bonding with B, and P with Z.

That’s where the similarities fade out. These new ‘letters’ introduce dozens of new chemical parameters to the double helix structure that potentially affect how it zips and twists.

By devising models that predict the molecule’s stability and then observing actual structures made of this ‘alien’ DNA, researchers are better equipped what’s truly important when it comes to the fundamentals of a genetic template.

The researchers constructed hundreds of hachimoji helices made up of different configurations of natural and synthetic bases and then subjected them to a range of conditions to see how well they held up.

While there were a few minor differences in how the new letters behaved, there was no reason to believe hachimoji DNA wouldn’t work well as an information-carrying template that could mutate and evolve.

The team not only showed their synthetic letters could contribute to new codes without swiftly disintegrating, the sequences were also translated into synthetic RNA versions.

Their work falls well short of a second genesis. But a novel DNA format such as this is a step towards determining what living chemistry might – and might not – look like elsewhere in the Universe.

“Life detection is an increasingly important goal of NASA’s planetary science missions, and this new work will help us to develop effective instruments and experiments that will expand the scope of what we look for,” says NASA’s Planetary Science Division’s acting director, Lori Glaze.

Devising new bases that can operate alongside our own DNA also has applications closer to home, not only as a way to reprogram life with a different code base, but in our effort to build new kinds of nanostructures.

The sky really isn’t the limit with synthetic DNA. This is going to take us to the stars and back again.

This research was published in Science.