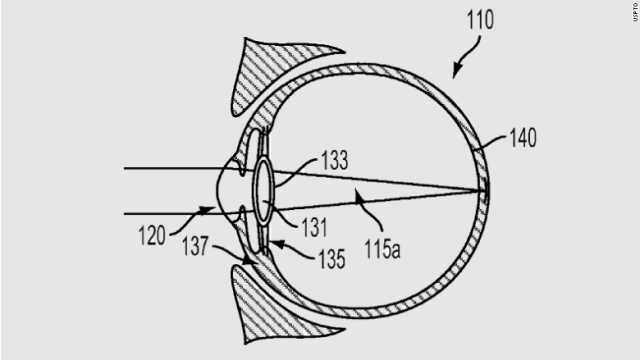

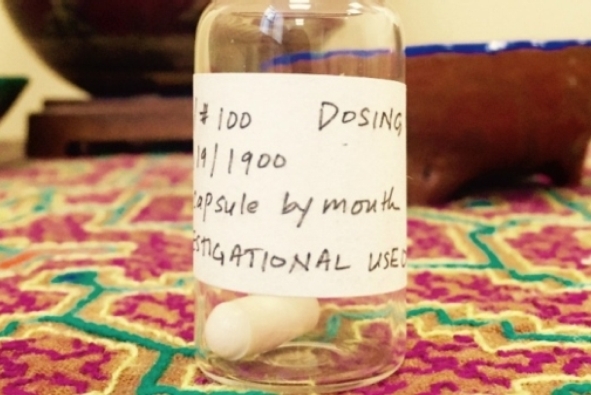

Synthetic psilocybin, a compound found in magic mushrooms, has been administered to cancer patients in a study at New York University. Researcher Anthony Bossis says many subjects report decreased depression and fear of death after their session. Although some patients do not report persistent positive feelings, none report persistent adverse effects. Photo: Bossis, NYU.

By John Horgan

Bossis, a psychologist at New York University, belongs to an intrepid cadre of scientists reviving research into psychedelics’ therapeutic potential. I say “reviving” because research on psychedelics thrived in the 1950s and 1960s before being crushed by a wave of anti-psychedelic hostility and legislation.

Psychedelics such as LSD, psilocybin and mescaline are still illegal in the U.S. But over the past two decades, researchers have gradually gained permission from federal and other authorities to carry out experiments with the drugs. Together with physicians Stephen Ross and Jeffrey Guss, Bossis has tested the potential of psilocybin—the primary active ingredient of “magic mushrooms”–to alleviate anxiety and depression in cancer patients.

Journalist Michael Pollan described the work of Bossis and others in The New Yorker last year. Pollan said researchers at NYU and Johns Hopkins had overseen 500 psilocybin sessions and observed “no serious adverse effects.” Many subjects underwent mystical experiences, which consist of “feelings of unity, sacredness, ineffability, peace and joy,” as well as the conviction that you have discovered “an objective truth about reality.”

Pollan’s report was so upbeat that I felt obliged to push back a bit, pointing out that not all psychedelic experiences—or mystical ones–are consoling. In The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James emphasized that some mystics have “melancholic” or “diabolical” visions, in which ultimate reality appears terrifyingly alien and uncaring.

Taking psychedelics in a supervised research setting doesn’t entirely eliminate the risk of a bad trip. That lesson emerged from a study in the early 1990s by psychiatrist Rick Strassman, who injected dimethyltryptamine, DMT, into human volunteers.

From 1990 to 1995, Strassman supervised more than 400 DMT sessions involving 60 subjects. Many reported dissolving blissfully into a radiant light or sensing the presence of a loving god. But 25 subjects had “adverse effects,” including terrifying hallucinations of “aliens” that took the shape of robots, insects or reptiles. (For more on Strassman’s study, see this link: https://www.rickstrassman.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=61&Itemid=60

Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann, who discovered LSD’s powers in 1943 and later synthesized psilocybin, sometimes expressed misgivings about psychedelics. When I interviewed him in 1999, he said psychedelics have enormous scientific, therapeutic and spiritual potential. He hoped someday people would take psychedelics in “meditation centers” to awaken their religious awe.

Yet in his 1980 memoir LSD: My Problem Child, Hofmann confessed that he occasionally regretted his role in popularizing psychedelics, which he feared represent “a forbidden transgression of limits.” He compared his discoveries to nuclear fission; just as fission threatens our fundamental physical integrity, so do psychedelics “attack the spiritual center of the personality, the self.”

I had these concerns in mind when I attended a recent talk by Bossis near New York University. A large, bearded man who exudes warmth and enthusiasm, Bossis couldn’t reveal details of the cancer-patient study, a paper on which is under review, but he made it clear that the results were positive.

Many subjects reported decreased depression and fear of death and “improved well-being” after their session. Some called the experience among the best of their lives, with spiritual implications. An atheist woman described feeling “bathed in God’s love.”

Bossis said psychedelic therapy could transform the way people die, making the experience much more meaningful. He quoted philosopher Victor Frankl, who said, “Man is not destroyed by suffering. He is destroyed by suffering without meaning.”

During the Q&A, I asked Bossis about bad trips. Wouldn’t it be awful, I suggested, if a dying patient’s last significant experience was negative? Bossis said he and his co-researchers were acutely aware of that risk. They minimized adverse reactions by managing the set (i.e., mindset, or expectations, of the subject) and setting (context of the session).

First, they screen patients for mental illness, eliminating those with, say, a family history of schizophrenia. Second, the researchers prepare patients for sessions, telling them to expect and explore rather than suppressing negative emotions, such as fear or grief. Third, the sessions take place in a safe, comfortable room, which patients can decorate with personal items, such as photographs or works of art. A researcher is present during sessions but avoids verbal interactions that might distract the patient from her inner journey. Patients and researchers generally talk about sessions the following day.

These methods seem to work. Some patients, to be sure, became frightened or melancholy. One dwelled on the horrors of the Holocaust, which had killed many members of his family, but he found the experience meaningful. Some patients did not emerge from their sessions with persistent positive feelings, Bossis said, but none reported persistent adverse effects.

Bossis has begun a new study that involves giving psilocybin to religious leaders, such as priests and rabbis. His hope is that these subjects will gain a deeper understanding of the mystical roots of their faiths.

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/psychedelic-therapy-and-bad-trips/