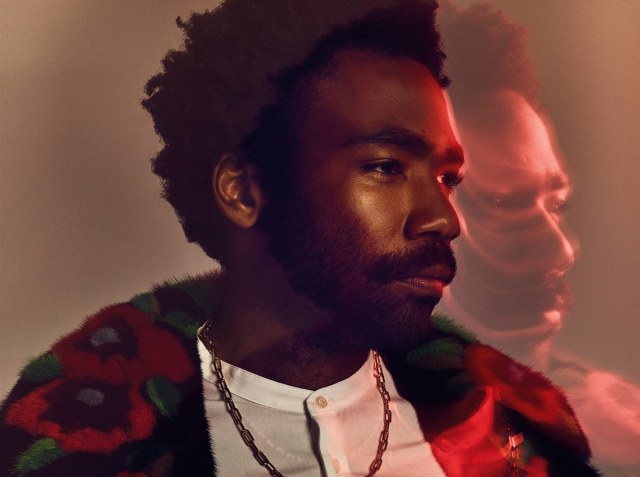

DONALD GLOVER WISHES people would clap more. Not that they should applaud—he gets enough applause when he performs stand-up or when he gets recognized from Atlanta, the TV show he both writes and stars in. No, Glover’s talking about clapping to a beat. “I was listening to Donny Hathaway’s album Live at the Troubadour,” he says. “You hear the crowd harmonizing with every song and clapping to the beat on time. You don’t hear that at concerts anymore.”

It’s an odd thing to notice, maybe, but Glover has been listening to a lot of Hathaway lately, and to Bill Withers too—another soulful ballad singer. This may be part of the reason his onstage persona, Childish Gambino, has drifted from hip hop to something else. His latest album, Awaken, My Love!, sounds more like James Brown or Sly and the Family Stone. Possibly with a little Pink Floyd.

But more than that, Glover has been thinking a lot about performance and the different ways a performer can interact with an audience. Maybe it’s like church, he says, like gospel music. In many African American churches, clapping hands and tapping feet were requirements for attendance.“I don’t think black people go to church like that anymore,” Glover says.

Glover’s giving audiences someplace new where they can clap along. Lots of new places, actually. There’s the Burning Man–ish three-day concert in the desert that teed up his new album. Or, if you didn’t make it there, you can grab the virtual reality experience that goes along with it. Or just stream the album itself.

He has, in other words, a lot going on. There’s his TV show Atlanta, the stand-up comedy, and the weird supporting roles in giant movies (Glover was a rocket scientist who came up with the plan to save Matt Damon in The Martian). Oh, and he’s going to play Lando Calrissian in the Han Solo prequel Star Wars movie, set to begin filming in early 2017.

How does a young hyphenate put together a career like that in a time of entertainment-industry turmoil? A team of creative advisers and managers helps, but Glover was early to the multiplatform artist party. All of his projects intersect in strange, intertextual ways. So amid all the different platforms, there’s also world-building going on (both metaphorically and, with his new project, virtually). Glover may not be as mass-culture as some of the other artists experimenting in this territory—Beyoncé, Drake—but his ambition is to create something entirely new.

GLOVER GREW UP in Stone Mountain, Georgia, about 20 miles east of Atlanta; his mother ran a day care center and didn’t much care for music, but his father, a Postal Service worker, played everything from Hall & Oates to Funkadelic to the Police. “I remember listening to some of my dad’s music as a kid, like Parliament. I’d hear a woman moaning and groaning, and it was so scary because she sounded terrified,” Glover says. “That music was filled with so many different real emotions and feelings that you could listen to it again and again.”

By day, Glover lived in his imagination. His Jehovah’s Witness upbringing meant no television. He’d listen to bootleg audio of Simpsons episodes in bed at night, though he did manage to sneak into a viewing of Star Wars: Episode I and catch the occasional Muppet movie. It was a little weird, and he translated that weirdness into his own puppet shows, performing for the foster kids his parents took care of. “Being a Jehovah’s Witness amplified my own alienness,” he says. “Jehovah’s Witnesses don’t celebrate Christmas. You don’t pledge allegiance to the flag. People don’t understand that.”

But Glover understands people. He has an almost preternatural emotional intelligence; when we meet for the second time I give him a hug, and he calls me out on it: “What’s up with that hug? That didn’t have any feeling! Where’s my hug?” I try again. Glover is happily missing much of the stifling bravado that weighed down far too many male African American performers in, say, the 1990s. He’s in touch with all his feelings, and he seems to think everyone else should be too.

Combine youth, empathy, alienation, and love of performance and you get a drama major. Glover went to college at New York’s Tisch School of the Arts, where he joined an improv comedy group. When Tina Fey saw some of the short videos Glover made there, she hired him to write for her popular TV show 30 Rock. He had never written for television; he was 23 years old.“I decided I wanted to write for television because of Tina,” Glover says. “She was always so happy, and I was like, I want to be happy like that too.”

It worked. He was happy. He did stand-up, made funny sketch comedy videos on YouTube, wrote for 30 Rock for three seasons, and eventually joined the cast of the cult-hit sitcom Community, playing the young, earnest, deeply nerdy Troy—the only mostly normal person (a plumber messiah, but still). It was starting to seem like Glover could make a career out of that kind of code switch, an African American cast before a mostly white audience.

In 2011 Glover donned the Childish Gambino identity he’d worn in a few comedy videos and mixtapes and released a rap album. It was more hipster than hip hop, to be honest, and earned mixed reviews, but it got him a whole new audience—and his second album got two Grammy nominations. Small but significant parts in The Martian and Magic Mike XXL did even more. Whatever Glover did, more and more people were starting to clap along to the beat. A team of managers, artists, and technologists—Glover calls them Royalty—has had a say in almost every move in his career since 2012. At the core are Glover’s younger brother Steve and Glover’s manager, Chad Taylor. Fam Udeorji joined when Taylor met him on the road with Childish Gambino. They formed a management company, Wolf and Rothstein—Wolf is Taylor’s nickname, and Udeorji named himself after Ace Rothstein, Robert De Niro’s character in Casino.

Taylor and Udeorji manage a few other musicians who often hang out with Royalty and offer input. Ibra Ake, a photographer and art director, is the visual and creative expert. Glover’s artist buddy Swank rounds out the group. Hiro Murai, who directed a bunch of Childish Gambino videos, and producer Ludwig Göransson often hang out too. Gathered together for drinks in a Beverly Hills café, the subset of Glover’s team who join us look a little like fraternity brothers—not the jerk kind, the cute, smart, and nerdy kind. They used to meet every day, before the responsibilities of fatherhood started to rule Glover’s time, in a house he rented from Chris Bosh of the Miami Heat. “We’d just roll out ideas while making a sandwich or talking about life,” Udeorji says.

That’s how the idea for Atlanta began to come together. It was Glover’s hometown region, of course, but he had more in mind than just depicting a city that has become a cultural center for African Americans—Glover also wanted to explore what it’s like to be young, talented, and black in the South. He had in mind two other African American–led TV programs, from the comedians Bernie Mac and Dave Chappelle. “Those shows were so honest and so true,” Glover says. “Bernie Mac had a sister who was a crack addict on the show. It wasn’t funny, but it was real.”

To the FX network, Glover pitched the idea of a black Ivy League dropout who returns to Atlanta and begins managing his drug-dealing cousin’s fledging rap career. It’d have drama, comedy, and music but also deal with issues like mass incarceration, poverty, drug use, and fatherhood in the black community. “We like to sit down with artists a few times and listen to what they say about their project,” says John Landgraf, president and general manager of FX. “With Donald, he didn’t always articulate his vision in a way that we could see it, but his passions and ambition were clear. So we felt confident in the story he wanted to tell and how he wanted to tell it.” The challenge would be in getting the language and tone of the show right. Mess that up and Atlanta would be considered irrelevant or—worse—totally wack. Glover solved the problem in a way that is, in retrospect, obvious but practically unheard of in Hollywood: an all-black writing team, which included a few names that had never written a script for television before. “It wasn’t a conscious decision, really,” Glover says. “I knew I wanted people with similar experiences who understood the language and the mindset of the characters and their environment.”

Still, television is an industry that has only recently begun to acknowledge the need for diversity in front of the camera,much less behind it. “Listen, even BET wouldn’t have given him that much freedom,” says one television and film executive.“An all-black writers’ room is one thing, but for me it’s the number of writers who hadn’t written on a show before at all. Most networks aren’t going to take that chance.”

And it’s true, says Udeorji—one of the writers—that other networks didn’t really get the concept. But even though there were times when FX wasn’t exactly sure where Glover’s team was headed, the network let them go there. “Donald’s a rapper who has unique experience, because he worked with Tina Fey and that crew early on. That gave him a lot of clout with the network,” Udeorji says. “He showed us the ropes of character development and story structure and took the leadership role in the room, and then we just let the ideas out.”

That dynamic has led to some genre-breaking storytelling. Atlanta is a half-hour comedy about black people that makes no extra effort to explain black people to its viewers. You either get it or you don’t. One episode, “Value,” spends an entire scene at a dinner with Van (ex-girlfriend of Earn, Glover’s character) and her best friend. It’s 10 minutes of the most nuanced dialog seen on television between two women of color as they land brutally honest viewpoints on each other’s complicated lives. “That scene blew me away,” said Cheo Hodari Coker, a longtime TV writer who runs the Netflix show Luke Cage. “You never see that amount of time given to straight dialog. It was so real, like you were eavesdropping on someone’s conversation. That’s good television.”

The crew even contributed visual flair. “I like it when black people are hit with a certain light, like purple,” Glover says. So he and Murai started experimenting.“It just felt good to play around with the look of the show.”

IN EARLY 2016, with Atlanta in production, Glover was also thinking about his next album.

Roughly, he already knew what he wanted. “He came into our offices with a five-year vision of his music and the visuals that were to go with it,” says Daniel Glass, president of Glassnote Records, Glover’s label. “There aren’t a lot of artists that have that kind of clarity about where their career is headed.”

But fatherhood had altered his course. Glover doesn’t live particularly publicly—he didn’t announce his son’s birth on social media, for example—but he acknowledges that being a dad changed his ideas about some things. He spent months returning to the sounds of his own childhood, listening to the music his father played, and the first single from the new album, “Me and Your Mama” is a highly charged, funked-out lullaby of sorts for his new little one.

More than that, he wanted to find yet another way to connect with fans—not a traditional concert but what Glover describes as a “shared vibration.” He called Udeorji and Taylor with the concept: a three-day camping trip/performance installation in the desert to debut new songs and show off wild new visuals. Glover called it Pharos, named for the lighthouse at Alexandria, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. “We were inspired by Kanye and other artists, but the vision for most things comes from Donald,” Taylor says. “For us it became figuring out how to make it all happen.”

They watched concert films and talked about imagery they liked—for example, the digital mountain from Kanye’s Yeezus tour in 2013. But bringing fans in became Miles Konstantin’s job. The 22-year-old had started a fan site for Childish Gambino in high school that so impressed Glover, he hired the kid. Konstantin studied physics in college by day, and he and his two roommates worked on Glover’s website at night.

For Pharos, Konstantin designed an app with a countdown anda slowly approaching planet Earth—and the option to buy a ticket to something for $99, locked to the owner of the phone and therefore unscalpable. (Glover wanted to keep ticket prices down.)

Once you bought a ticket, you got a guidebook and an app-based manifesto about the human condition during the digital age. The first shows sold out in six minutes; Glover added two more. But the concert came with a draconian rule: Members of the audience would have to surrender their phones on entry. “Today, kids’ idea of going to a concert is proving that they are there on Snapchat or Instagram,” Glover says. “We wanted to give them a complete show and have their attention.”

Even that didn’t dissuade anyone. “We weren’t completely sure how fans would handle that part, but Donald’s fans are very open-minded,” Konstantin says.

Step two: Build the set. The concerts would happen in a giant white dome in Joshua Tree, California. Dancing zombies and ghostlike creatures would sway to the tunes on screens and interact with sounds in their environments. Glover performed in a yellow grass skirt, long cornrows, and glow-in-the-dark tribal war paint. It was like a cross between Captain EO and Fantasia,complete with a grand finale flight through space, featuring planets moving to the beat.

To get it all right, Glover went to Microsoft. “He came in with his music and a story and asked how we could accommodate his ideas,” says Fred Warren, creative director for the company. When the computer-generated characters planned for massive screens inside the performance dome weren’t moving the way Glover’s group envisioned, Warren’s team figured they had only one choice: Go to the source. “We decided the best way to showcase the moves on the screen was to have Donald create them and use Kinect sensors to capture his every dance move.” Glover spent a day at Microsoft’s New York office performing the movements of the zombies and ghosts, much like in those puppet shows he used to put on as a kid.

Beyond the high tech animation, the new Childish Gambino album is pretty great. Awaken, My Love! is a chaotic mix of funk, punk, and R&B infused with a new age vibe. On more than a few tracks, Glover uses falsetto like Luther Vandross—and Withers and Hathaway.

And once Microsoft had all that mo-capped performance and computer-generated set design, the next step was almost self-evident. You can buy Awaken, My Love! on old-school vinyl, but you can also watch the video in way-new-school virtual reality using your mobile device. 1 It’s not quite like seeing Pharos in Joshua Tree, but it’s close.

DAVE CHAPPELLE WALKED away from his wildly popular eponymous show on Comedy Central (and the $50 million that came with it) in 2005. He was arguably at the peak of his success, but the mercurial comedian had begun to feel that white audiences were laughing at his sketches and jokes about black people without absorbing them, without picking up the social message.

Glover has made himself a student of Chappelle’s, including trying to understand that specific kind of disconnect with the audience. “On some level, the situation Dave faced is probably already happening,” Glover says. “But that’s why it’s so good to have a room filled with people who understand what you’re trying to do. You’ve got to have someone willing to say ‘I don’t enjoy that.’ That makes you step back and rethink when someone says that shit doesn’t work.”

The parallel to Chappelle isn’t a perfect one. Both are influential African American comedians, but their MOs aren’t equivalent. Glover is much younger and fundamentally a well-adjusted, middle-class kid. When he performs, he’s not drawing from anger or a tough childhood. He’s connecting to a wider emotional spectrum, and that seems to give him a broader performance palette. Even Chappelle—a fan of Glover’s—acknowledges the differences. “I can’t keep up with all the shit he’s doing, but it’s all damn good. That he can do it all blows me away,” Chappelle says. “But my show was a sketch show, and Donald’s is more of a regular sitcom. And then we’re in a different time. Race is more nuanced today, and that helps the message. It’s been 10 years.”

A lot changes in a decade. If Chappelle and the late Bernie Mac opened up possibilities for a performer like Glover, now it’s Glover’s turn to rough out a frame for the next generation. Leveraging personal work to reach unpredictable audiences who stay loyal through unpredictable projects won’t be unusual—it’ll be the norm. And that’ll encourage more weird media, beyond live shows and VR, and even more unpredictability. Chappelle’s Show wore its politics on its sleeve—the things Chappelle wanted you to understand were text. Atlanta and the music and video work of Childish Gambino are about feelings and subtext, opening new worlds for creators to explore and audiences to experience. The worlds may be odd and their rhythms idiosyncratic—but you’re going to want to clap along.

https://www.wired.com/2017/01/childish-gambino-donald-glover/