by Peter Mellgard

Back in the 80s there was a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who confessed to a professor that he hadn’t quite figured out “this sex thing,” and preferred to spend time on his computer rather than with girls. For “Anthony,” computers were safer and made more sense; romantic relationships, he said, usually led to him “getting burned in some way.”

Years later, Anthony’s story made a big impression on David Levy, an expert in artificial intelligence, who was amazed that someone as educated as Anthony was developing an emotional attachment to his computer so long ago. Levy decided he wanted to give guys like Anthony a social and sexual alternative to real girls. The answer, he thinks, is sexbots. And he’s not talking about some blow-up doll that doesn’t talk.

Levy predicts that a lot of us, mostly but not exclusively shy guys like Anthony, will be having sex with robots sometime around the 2040s. By then, he says, robots will be so hot, human-like and mind-blowing under the sheets that a lot of people will find them sexually enjoyable. What’s more, Levy believes they will be able to engage and communicate with people in a meaningful, emotional way, so that guys like Anthony won’t need to worry about real girls if they don’t want to.

To give a robot the ability to communicate and provide the kind of emotional satisfaction someone would normally get from a human partner, Levy is improving an award-winning chat program called Do-Much-More that he built a few years ago. His aim is for it to become “a girlfriend or boyfriend chatbot that will be able to conduct amorous conversations with a user,” he told The WorldPost. “I’m trying to simulate the kind of conversation that two lovers might have.”

Levy admits that “this won’t come about instantly.” Eventually he wants his advanced conversation software embedded in a sexbot so that it becomes more than just a sexual plaything — a companion, perhaps. But it won’t be for everyone. “I don’t believe that human-robot relationships are going to replace human-human relationships,” he said.

There will be people, however, Levy said, people like Anthony maybe, for whom a sexbot holds a strong appeal. “I’m hoping to help people,” he said, then elaborated:

People ask me the question, ‘Why is a relationship with a robot better than a relationship with a human?’ And I don’t think that’s the point at all. For millions of people in the world, they can’t make a good relationship with other humans. For them the question is not, ‘Why is a relationship with a robot better?’ For them the question is, would it be better to have a relationship with a robot or no relationship at all?

The future looks bright if you’re into relationships with robots and computers.

Neil McArthur, a professor of philosophy and ethics at the University of Manitoba in Canada, imagines that in 10 to 15 years, “we will have something for which there is great consumer demand and that people are willing to say is a very good and enjoyable sexbot.”

For now, the closest thing we have to a genuine sexbot is the RealDoll. A RealDoll is the most advanced sex doll in the world — a sculpted “work of art,” in the words of Matt McMullen, the founder of the company, Abyss Creations, that makes them. For a few thousand dollars a pop, customers can customize the doll’s hair color, skin tone, eyes, clothing and genitalia (removable, exchangeable, flaccid, hard) — and then wait patiently for a coffin-sized box to arrive in the mail. For some people, that box contains a sexual plaything and an emotional companion that is preferable to a human partner.

“The goal, the fantasy, is to bring her to life,” McMullen told Vanity Fair.

Others already prefer virtual “people” to living humans as emotional partners. Love Plus is a hugely popular game in Japan that is played on a smartphone or Nintendo. Players take imaginary girls on dates, “kiss” them, buy them birthday cakes.

“Well, you know, all I want is someone to say good morning to in the morning and someone to say goodnight to at night,” said one gamer who has been dating one of the imaginary girls for years, according to TIME Magazine.

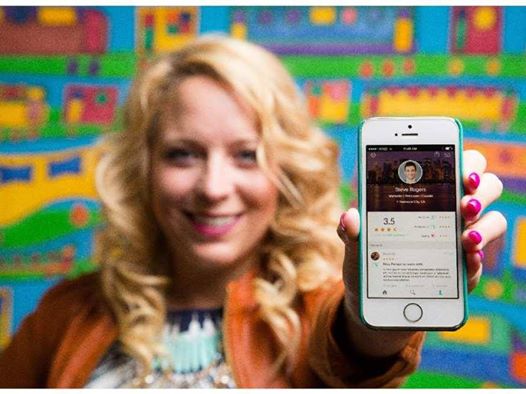

And there’s Invisible Girlfriend and Invisible Boyfriend, apps that connects you with a real, paid human who will text you so that you can prove you have a girlfriend or boyfriend to nosy relatives or disbelieving buddies. At least one user, a culture critic for the Washington Post, confessed she might actually being in love with the person on the other side who, remember, is being paid to satisfy customers’ desires. They’d never even met.

McArthur and others suspect that there might be people for whom a sexbot is no mere toy but a way to access something — sex — that for one reason or another was previously unattainable.

When it comes to the disabled, McArthur explained, there are two barriers to sexual activity: an external — “they’re not seen as valuable sexual partners” — and an internal anxiety. “Sexbots can give them access to partners. And they are sort of a gateway as well: disabled people could use a sexbot to build confidence and to build a sense of sexuality.”

“When it comes to sex,” he concluded, “more is better.”

It’s a new and emerging technology, but let’s nip in the bud,” Kathleen Richardson, a senior research fellow in the ethics of robotics at De Montfort University in England, told the Washington Post. Richardson released a paper this month titled “The Asymmetrical ‘Relationship’: Parallels Between Prostitution and the Development of Sex Robots.”

“I propose that extending relations of prostitution into machines is neither ethical, nor is it safe,” the paper reads.

And the ethical questions extend beyond machine “prostitution.” RealDoll, the sex doll company, refuses to make child-like dolls or animals. But what if another company does?

“It’s really a legal, moral, societal debate that we need to have about these systems,” said Matthias Scheutz, the director of the human-robot interaction laboratory at Tufts University. “We as a society need to discuss these questions before these products are out there. Because right now, we aren’t.”

If, in the privacy of your own home, you want to have sex with a doll or robot that looks like a 10-year-old boy or virtual children in porn apps, is that wrong? In most though not all countries in the world, it’s illegal to possess child pornography, including when it portrays a virtual person that is “indistinguishable” from a real minor. But some artistic representations of naked children are legal even in the U.S. Is a sexbot art? Is what a person does to a sexbot, no matter what it looks like, a legal question?

Furthermore, the link between viewing child pornography and child abuse crimes is unclear. Studies have been done on people incarcerated for those crimes that found that child pornography fueled the desire to abuse a real child. But another study on self-identified “boy-attracted pedosexual males” found that viewing child pornography acted as a substitute for sexual molestation.

“I think the jury is out on that,” said McArthur. “It depends on an empirical question: Do you think that giving people access to satisfaction of that kind is going to stimulate them to move on to actual contact crimes, or do you think it will provide a release valve?”

Scheutz explained: “People will build all sorts of things. Some people have made arguments that for people who otherwise would be sex offenders, maybe a child-like robot would be a therapeutic thing. Or it could have exactly the opposite effect.”

McArthur is most worried about how sexbots will impact perceptions about gender, body image and human sexual behavior. Sexbots will “promote unattainable body ideals,” he said. Furthermore, “you just aren’t going to make a robot that has a complicated personality and isn’t always in the mood. That’s going to promote a sense that, well, women should be more like an idealized robot personality that is a pliant, sexualized being.”

As sexbots become more popular and better at what they’re built to do, these questions will become more and more important. We, as a society and a species, are opening a door to a new world of sex. Social taboos will be challenged; legal questions will be raised.

And there might be more people — maybe people like Anthony — who realize they don’t need to suffer through a relationship with a human if they don’t want to because a robot provides for their emotional and sexual needs without thinking, contradicting, saying no or asking for much in return.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/robot-sex_55f979f2e4b0b48f670164e9

Thanks to Dr. Lutter for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.