by Michael Graziano

Imagine scanning your Grandma’s brain in sufficient detail to build a mental duplicate. When she passes away, the duplicate is turned on and lives in a simulated video-game universe, a digital Elysium complete with Bingo, TV soaps, and knitting needles to keep the simulacrum happy. You could talk to her by phone just like always. She could join Christmas dinner by Skype. E-Granny would think of herself as the same person that she always was, with the same memories and personality—the same consciousness—transferred to a well regulated nursing home and able to offer her wisdom to her offspring forever after.

And why stop with Granny? You could have the same afterlife for yourself in any simulated environment you like. But even if that kind of technology is possible, and even if that digital entity thought of itself as existing in continuity with your previous self, would you really be the same person?

Is it even technically possible to duplicate yourself in a computer program? The short answer is: probably, but not for a while.

Let’s examine the question carefully by considering how information is processed in the brain, and how it might be translated to a computer.

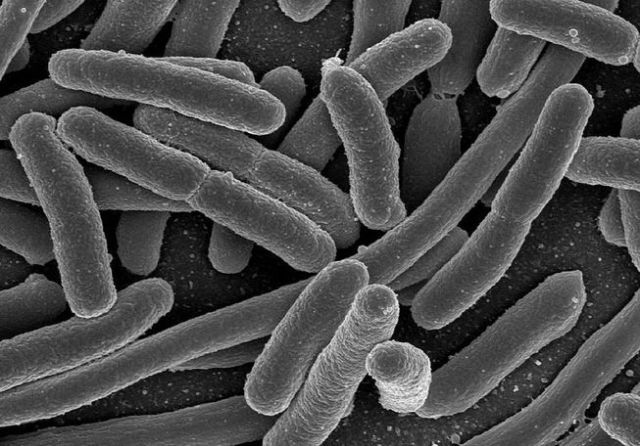

The first person to grasp the information-processing fundamentals of the brain was the great Spanish neuroscientist, Ramon Y Cajal, who won the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology. Before Cajal, the brain was thought to be made of microscopic strands connected in a continuous net or ‘reticulum.’ According to that theory, the brain was different from every other biological thing because it wasn’t made of separate cells. Cajal used new methods of staining brain samples to discover that the brain did have separate cells, which he called neurons. The neurons had long thin strands mixing together like spaghetti—dendrites and axons that presumably carried signals. But when he traced the strands carefully, he realized that one neuron did not grade into another. Instead, neurons contacted each other through microscopic gaps—synapses.

Cajal guessed that the synapses must regulate the flow of signals from neuron to neuron. He developed the first vision of the brain as a device that processes information, channeling signals and transforming inputs into outputs. That realization, the so-called neuron doctrine, is the foundational insight of neuroscience. The last hundred years have been dedicated more or less to working out the implications of the neuron doctrine.

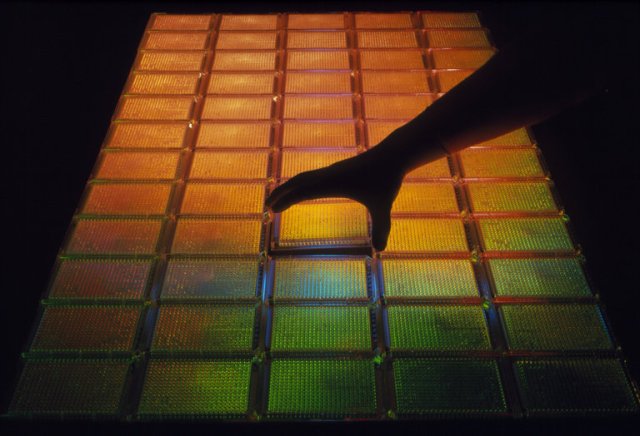

It’s now possible to simulate networks of neurons on a microchip and the simulations have extraordinary computing capabilities. The principle of a neural network is that it gains complexity by combining many simple elements. One neuron takes in signals from many other neurons. Each incoming signal passes over a synapse that either excites the receiving neuron or inhibits it. The neuron’s job is to sum up the many thousands of yes and no votes that it receives every instant and compute a simple decision. If the yes votes prevail, it triggers its own signal to send on to yet other neurons. If the no votes prevail, it remains silent. That elemental computation, as trivial as it sounds, can result in organized intelligence when compounded over enough neurons connected in enough complexity.

The trick is to get the right pattern of synaptic connections between neurons. Artificial neural networks are programmed to adjust their synapses through experience. You give the network a computing task and let it try over and over. Every time it gets closer to a good performance, you give it a reward signal or an error signal that updates its synapses. Based on a few simple learning rules, each synapse changes gradually in strength. Over time, the network shapes up until it can do the task. That deep leaning, as it’s sometimes called, can result in machines that develop spooky, human-like abilities such as face recognition and voice recognition. This technology is already all around us in Siri and in Google.

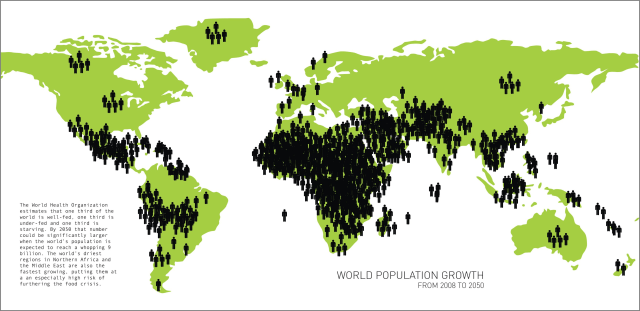

But can the technology be scaled up to preserve someone’s consciousness on a computer? The human brain has about a hundred billion neurons. The connectional complexity is staggering. By some estimates, the human brain compares to the entire content of the internet. It’s only a matter of time, however, and not very much at that, before computer scientists can simulate a hundred billion neurons. Many startups and organizations, such as the Human Brain project in Europe, are working full-tilt toward that goal. The advent of quantum computing will speed up the process considerably. But even when we reach that threshold where we are able to create a network of a hundred billion artificial neurons, how do we copy your special pattern of connectivity?

No existing scanner can measure the pattern of connectivity among your neurons, or connectome, as it’s called. MRI machines scan at about a millimeter resolution, whereas synapses are only a few microns across. We could kill you and cut up your brain into microscopically thin sections. Then we could try to trace the spaghetti tangle of dendrites, axons, and their synapses. But even that less-than-enticing technology is not yet scalable. Scientists like Sebastian Seung have plotted the connectome in a small piece of a mouse brain, but we are decades away, at least, from technology that could capture the connectome of the human brain.

Assuming we are one day able to scan your brain and extract your complete connectome, we’ll hit the next hurdle. In an artificial neural network, all the neurons are identical. They vary only in the strength of their synaptic interconnections. That regularity is a convenient engineering approach to building a machine. In the real brain, however, every neuron is different. To give a simple example, some neurons have thick, insulated cables that send information at a fast rate. You find these neurons in parts of the brain where timing is critical. Other neurons sprout thinner cables and transmit signals at a slower rate. Some neurons don’t even fire off signals—they work by a subtler, sub-threshold change in electrical activity. All of these neurons have different temporal dynamics.

The brain also uses hundreds of different kinds of synapses. As I noted above, a synapse is a microscopic gap between neurons. When neuron A is active, the electrical signal triggers a spray of chemicals—neurotransmitters—which cross the synapse and are picked up by chemical receptors on neuron B. Different synapses use different neurotransmitters, which have wildly different effects on the receiving neuron, and are re-absorbed after use at different rates. These subtleties matter. The smallest change to the system can have profound consequences. For example, Prozac works on people’s moods because it subtly adjusts the way particular neurotransmitters are reabsorbed after being released into synapses.

Although Cajal didn’t realize it, some neurons actually do connect directly, membrane to membrane, without a synaptic space between. These connections, called gap junctions, work more quickly than the regular kind and seem to be important in synchronizing the activity across many neurons.

Other neurons act like a gland. Instead of sending a precise signal to specific target neurons, they release a chemical soup that spreads and affects a larger area of the brain over a longer time.

I could go on with the biological complexity. These are just a few examples.

A student of artificial intelligence might argue that these complexities don’t matter. You can build an intelligent machine with simpler, more standard elements, ignoring the riot of biological complexity. And that is probably true. But there is a difference between building artificial intelligence and recreating a specific person’s mind.

If you want a copy of your brain, you will need to copy its quirks and complexities, which define the specific way you think. A tiny maladjustment in any of these details can result in epilepsy, hallucinations, delusions, depression, anxiety, or just plain unconsciousness. The connectome by itself is not enough. If your scan could determine only which neurons are connected to which others, and you re-created that pattern in a computer, there’s no telling what Frankensteinian, ruined, crippled mind you would create.

To copy a person’s mind, you wouldn’t need to scan anywhere near the level of individual atoms. But you would need a scanning device that can capture what kind of neuron, what kind of synapse, how large or active of a synapse, what kind of neurotransmitter, how rapidly the neurotransmitter is being synthesized and how rapidly it can be reabsorbed. Is that impossible? No. But it starts to sound like the tech is centuries in the future rather than just around the corner.

Even if we get there quicker, there is still another hurdle. Let’s suppose we have the technology to make a simulation of your brain. Is it truly conscious, or is it merely a computer crunching numbers in imitation of your behavior?

A half-dozen major scientific theories of consciousness have been proposed. In all of them, if you could simulate a brain on a computer, the simulation would be as conscious as you are. In the Attention Schema Theory, consciousness depends on the brain computing a specific kind of self-descriptive model. Since this explanation of consciousness depends on computation and information, it would translate directly to any hardware including an artificial one.

In another approach, the Global Workspace Theory, consciousness ignites when information is combined and shared globally around the brain. Again, the process is entirely programmable. Build that kind of global processing network, and it will be conscious.

In yet another theory, the Integrated Information Theory, consciousness is a side product of information. Any computing device that has a sufficient density of information, even an artificial device, is conscious.

Many other scientific theories of consciousness have been proposed, beyond the three mentioned here. They are all different from each other and nobody yet knows which one is correct. But in every theory grounded in neuroscience, a computer-simulated brain would be conscious. In some mystical theories and theories that depend on a loose analogy to quantum mechanics, consciousness would be more difficult to create artificially. But as a neuroscientist, I am confident that if we ever could scan a person’s brain in detail and simulate that architecture on a computer, then the simulation would have a conscious experience. It would have the memories, personality, feelings, and intelligence of the original.

And yet, that doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods. Humans are not brains in vats. Our cognitive and emotional experience depends on a brain-body system embedded in a larger environment. This relationship between brain function and the surrounding world is sometimes called “embodied cognition.” The next task therefore is to simulate a realistic body and a realistic world in which to embed the simulated brain. In modern video games, the bodies are not exactly realistic. They don’t have all the right muscles, the flexibility of skin, or the fluidity of movement. Even though some of them come close, you wouldn’t want to live forever in a World of Warcraft skin. But the truth is, a body and world are the easiest components to simulate. We already have the technology. It’s just a matter of allocating enough processing power.

In my lab, a few years ago, we simulated a human arm. We included the bone structure, all the fifty or so muscles, the slow twitch and fast twitch fibers, the tendons, the viscosity, the forces and inertia. We even included the touch receptors, the stretch receptors, and the pain receptors. We had a working human arm in digital format on a computer. It took a lot of computing power, and on our tiny machines it couldn’t run in real time. But with a little more computational firepower and a lot bigger research team we could have simulated a complete human body in a realistic world.

Let’s presume that at some future time we have all the technological pieces in place. When you’re close to death we scan your details and fire up your simulation. Something wakes up with the same memories and personality as you. It finds itself in a familiar world. The rendering is not perfect, but it’s pretty good. Odors probably don’t work quite the same. The fine-grained details are missing. You live in a simulated New York City with crowds of fellow dead people but no rats or dirt. Or maybe you live in a rural setting where the grass feels like Astroturf. Or you live on the beach in the sun, and every year an upgrade makes the ocean spray seem a little less fake. There’s no disease. No aging. No injury. No death unless the operating system crashes. You can interact with the world of the living the same way you do now, on a smart phone or by email. You stay in touch with living friends and family, follow the latest elections, watch the summer blockbusters. Maybe you still have a job in the real world as a lecturer or a board director or a comedy writer. It’s like you’ve gone to another universe but still have contact with the old one.

But is it you? Did you cheat death, or merely replace yourself with a creepy copy?

I can’t pretend to have a definitive answer to this philosophical question. Maybe it’s a matter of opinion rather than anything testable or verifiable. To many people, uploading is simply not an afterlife. No matter how accurate the simulation, it wouldn’t be you. It would be a spooky fake.

My own perspective borrows from a basic concept in topology. Imagine a branching Y. You’re born at the bottom of the Y and your lifeline progresses up the stalk. The branch point is the moment your brain is scanned and the simulation has begun. Now there are two of you, a digital one (let’s say the left branch) and a biological one (the right branch). They both inherit the memories, personality, and identity of the stalk. They both think they’re you. Psychologically, they’re equally real, equally valid. Once the simulation is fired up, the branches begin to diverge. The left branch accumulates new experiences in a digital world. The right branch follows a different set of experiences in the physical world.

Is it all one person, or two people, or a real person and a fake one? All of those and none of those. It’s a Y.

The stalk of the Y, the part from before the split, gains immortality. It lives on in the digital you, just like your past self lives on in your present self. The right hand branch, the post-split biological branch, is doomed to die. That’s the part that feels gypped by the technology.

So let’s assume that those of us who live in biological bodies get over this injustice, and in a century or three we invent a digital afterlife. What could possibly go wrong?

Well, for one, there are limited resources. Simulating a brain is computationally expensive. As I noted before, by some estimates the amount of information in the entire internet at the present time is approximately the same as in a single human brain. Now imagine the resources required to simulate the brains of millions or billions of dead people. It’s possible that some future technology will allow for unlimited RAM and we’ll all get free service. The same way we’re arguing about health care now, future activists will chant, “The afterlife is a right, not a privilege!” But it’s more likely that a digital afterlife will be a gated community and somebody will have to choose who gets in. Is it the rich and politically connected who live on? Is it Trump? Is it biased toward one ethnicity? Do you get in for being a Nobel laureate, or for being a suicide bomber in somebody’s hideous war? Just think how coercive religion can be when it peddles the promise of an invisible afterlife that can’t be confirmed. Now imagine how much more coercive a demagogue would be if he could dangle the reward of an actual, verifiable afterlife. The whole thing is an ethical nightmare.

And yet I remain optimistic. Our species advances every time we develop a new way to share information. The invention of writing jump-started our advanced civilizations. The computer revolution and the internet are all about sharing information. Think about the quantum leap that might occur if instead of preserving words and pictures, we could preserve people’s actual minds for future generations. We could accumulate skill and wisdom like never before. Imagine a future in which your biological life is more like a larval stage. You grow up, learn skills and good judgment along the way, and then are inducted into an indefinite digital existence where you contribute to stability and knowledge. When all the ethical confusion settles, the benefits may be immense. No wonder people like Ray Kurzweil refer to this kind of technological advance as a singularity. We can’t even imagine how our civilization will look on the other side of that change.

http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/07/what-a-digital-afterlife-would-be-like/491105/

Thanks to Dan Brat for bringing this to the It’s Interesting community.