A one thousand year old Anglo-Saxon remedy for eye infections which originates from a manuscript in the British Library has been found to kill the modern-day superbug MRSA in an unusual research collaboration at The University of Nottingham.

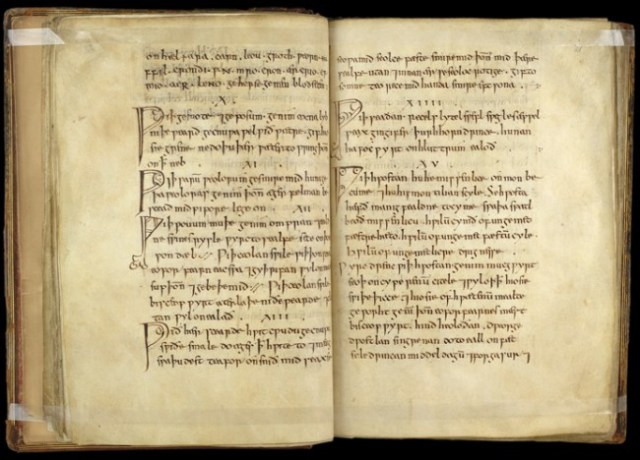

Dr Christina Lee, an Anglo-Saxon expert from the School of English has enlisted the help of microbiologists from University’s Centre for Biomolecular Sciences to recreate a 10th century potion for eye infections from Bald’s Leechbook an Old English leatherbound volume in the British Library, to see if it really works as an antibacterial remedy. The Leechbook is widely thought of as one of the earliest known medical textbooks and contains Anglo-Saxon medical advice and recipes for medicines, salves and treatments.

Early results on the ‘potion’, tested in vitro at Nottingham and backed up by mouse model tests at a university in the United States, are, in the words of the US collaborator, “astonishing”. The solution has had remarkable effects on Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) which is one of the most antibiotic-resistant bugs costing modern health services billions.

The team now has good, replicated data showing that Bald’s eye salve kills up to 90% of MRSA bacteria in ‘in vivo’ wound biopsies from mouse models. They believe the bactericidal effect of the recipe is not due to a single ingredient but the combination used and brewing methods/container material used. Further research is planned to investigate how and why this works.

The testing of the ancient remedy was the idea of Dr Christina Lee, Associate Professor in Viking Studies and member of the University’s Institute for Medieval Research. Dr Lee translated the recipe from a transcript of the original Old English manuscript in the British Library.

The recipe calls for two species of Allium (garlic and onion or leek), wine and oxgall (bile from a cow’s stomach). It describes a very specific method of making the topical solution including the use of a brass vessel to brew it in, a straining to purify it and an instruction to leave the mixture for nine days before use.

The scientists at Nottingham made four separate batches of the remedy using fresh ingredients each time, as well as a control treatment using the same quantity of distilled water and brass sheet to mimic the brewing container but without the vegetable compounds.

The remedy was tested on cultures of the commonly found and hard to treat bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus, in both synthetic wounds and in infected wounds in mice.

The team made artificial wound infections by growing bacteria in plugs of collagen and then exposed them to each of the individual ingredients, or the full recipe. None of the individual ingredients alone had any measurable effect, but when combined according to the recipe the Staphylococcus populations were almost totally obliterated: about one bacterial cell in a thousand survived.

The team then went on to see what happened if they diluted the eye salve – as it is hard to know just how much of the medicine bacteria would be exposed to when applied to a real infection. They found that when the medicine is too dilute to kill Staphylococcus aureus, it interfered with bacterial cell-cell communication (quorum sensing). This is a key finding, because bacteria have to talk to each other to switch on the genes that allow them to damage infected tissues. Many microbiologists think that blocking this behaviour could be an alternative way of treating infection.

Dr Lee said: “We were genuinely astonished at the results of our experiments in the lab. We believe modern research into disease can benefit from past responses and knowledge, which is largely contained in non-scientific writings. But the potential of these texts to contribute to addressing the challenges cannot be understood without the combined expertise of both the arts and science.

“Medieval leech books and herbaria contain many remedies designed to treat what are clearly bacterial infections (weeping wounds/sores, eye and throat infections, skin conditions such as erysipelas, leprosy and chest infections). Given that these remedies were developed well before the modern understanding of germ theory, this poses two questions: How systematic was the development of these remedies? And how effective were these remedies against the likely causative species of bacteria? Answering these questions will greatly improve our understanding of medieval scholarship and medical empiricism, and may reveal new ways of treating serious bacterial infections that continue to cause illness and death.”

University microbiologist, Dr Freya Harrison has led the work in the laboratory at Nottingham with Dr Steve Diggle and Research Associate Dr Aled Roberts. She will present the findings at the Annual Conference of the Society for General Microbiology which starts on Monday 30th March 2015 in Birmingham.

Dr Harrison commented: “We thought that Bald’s eyesalve might show a small amount of antibiotic activity, because each of the ingredients has been shown by other researchers to have some effect on bacteria in the lab – copper and bile salts can kill bacteria, and the garlic family of plants make chemicals that interfere with the bacteria’s ability to damage infected tissues. But we were absolutely blown away by just how effective the combination of ingredients was. We tested it in difficult conditions too; we let our artificial ‘infections’ grow into dense, mature populations called ‘biofilms’, where the individual cells bunch together and make a sticky coating that makes it hard for antibiotics to reach them. But unlike many modern antibiotics, Bald’s eye salve has the power to breach these defences.”

Dr Steve Diggle added: “When we built this recipe in the lab I didn’t really expect it to actually do anything. When we found that it could actually disrupt and kill cells in S. aureus biofilms, I was genuinely amazed. Biofilms are naturally antibiotic resistant and difficult to treat so this was a great result. The fact that it works on an organism that it was apparently designed to treat (an infection of a stye in the eye) suggests that people were doing carefully planned experiments long before the scientific method was developed.”

Dr Kendra Rumbaugh carried out in vivo testing of the Bald’s remedy on MRSA infected skin wounds in mice at Texas Tech University in the United States. Dr Rumbaugh said: “We know that MRSA infected wounds are exceptionally difficult to treat in people and in mouse models. We have not tested a single antibiotic or experimental therapeutic that is completely effective; however, this ‘ancient remedy’ performed as good if not better than the conventional antibiotics we used.”

Dr Harrison concludes: “The rise of antibiotic resistance in pathogenic bacteria and the lack of new antimicrobials in the developmental pipeline are key challenges for human health. There is a pressing need to develop new strategies against pathogens because the cost of developing new antibiotics is high and eventual resistance is likely. This truly cross-disciplinary project explores a new approach to modern health care problems by testing whether medieval remedies contain ingredients which kill bacteria or interfere with their ability to cause infection”.