Being buried alive is usually near the top of any worst-ways-to-die list. But how about being buried alive 100 feet below the ocean surface in a tiny pocket of air? For Harrison Okene, a 29-year-old Nigerian boat cook, this nightmare scenario became a reality for nearly three grueling days.

The story began on May 26 at about 4:30 a.m., when Harrison Okene got up to use the restroom. His vessel, a Chevron oil service tugboat called the AHT Jascon-4, swayed in the choppy Atlantic waters just off the coast of Nigeria. What caused the tugboat to capsize remains a mystery, though a Chevron official later blamed a “sudden ocean swell.”

Okene was thrown from the crew restroom as the ship turned over. Water streamed in and swept him through the vessel’s bowels until he found himself in the toilet of an officer’s cabin. As the ship settled on the ocean floor, the water stopped rising. For the next 60 hours, Okene—who was without food, water, or light—listened to the sounds of ocean creatures scavenging through the ship on his dead crewmates. Like a living Phlebas the Phoenician, he recounted his life’s events while growing more resigned to his fate.

Unbelievably, Okene survived his underwater ordeal long enough to be rescued. Basic physics, it turned out, was on Okene’s side the whole time—even if Poseidon wasn’t.

When Maxim Umansky, a physicist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, read about Okene’s miraculous rescue, his interest was piqued. “For a physics question, it’s an interesting problem,” said Umansky. “Of course, I’m also glad the man survived and happy with the ending of his story.”

Umansky began conducting his own calculations to quantify the factors responsible for Okene’s survival. He also posed a question to a physics Web forum: How large does a bubble have to be to sustain a person with breathable air?

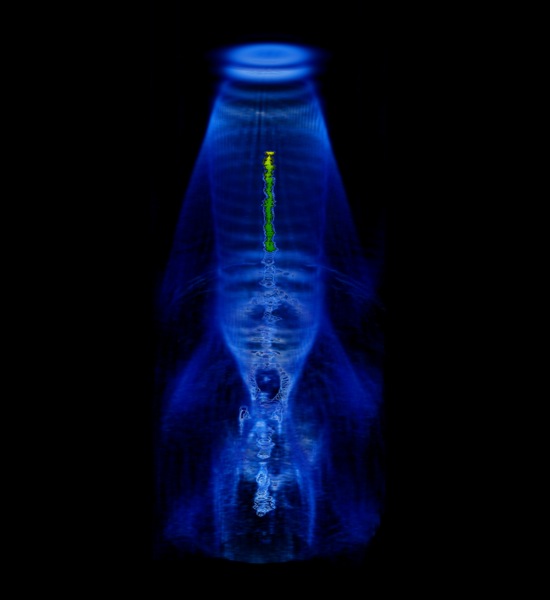

Okene’s salvation—the air bubble—was trapped because the overturned boat acted as a sort of diving bell, the cup-shaped chambers that have transported explorers and workers into the depths for centuries. In the fourth century B.C., Aristotle described the contraptions as enabling “the divers to respire equally well by letting down a cauldron, for this does not fill with water, but retains the air, for it is forced straight down into the water.” Years later, diving bells called caissons helped 19th-century workers construct the Brooklyn Bridge (though many died in the process).

Whether in a bell or boat, trapped air rises to the top of a concave chamber. The only way it can escape is by diffusing through the water itself, one molecule at a time. Eventually this would happen, but Okene would have succumbed to thirst, hypothermia, or asphyxiation long before his air bubble diffused into the ocean.

Fans of horror movies will note that asphyxiation typically claims victims of live burial. Carbon dioxide accounts for about 0.03 percent of normal air. If someone is trapped in an enclosed space, however, exhaling CO2 with every breath, the proportion of oxygen steadily decreases while the level of carbon dioxide increases. It’s the deadly CO2, not the lack of oxygen, that ultimately kills a person. Once the air reaches around 5 percent CO2, the victim becomes confused and panicked, starts hyperventilating, and eventually loses consciousness. Death follows. In an enclosed coffin, a person may produce deadly levels of carbon dioxide within two hours or so.

But Okene didn’t asphyxiate despite being trapped in a small, sealed space for 60 hours. How was this possible?

The water encapsulating his air bubble may have played a small role in his survival. Carbon dioxide, more so than oxygen or nitrogen, readily dissolves into water—especially cold water. The rate at which this occurs follows Henry’s law, a physics rule that states that the solubility of gas in a liquid is proportional to the pressure of the gas above the liquid. Disturbing the water’s surface, which increases its surface area, likewise increases the rate of transport of gaseous CO2 into the liquid. But if the volume of gas were too small to begin with—in other words, if deadly CO2 built up faster than it could diffuse away—that process wouldn’t have made much of a difference for Okene.

Humans require 10 cubic meters of air per day. So for Okene to continue breathing for 60 hours, he needed 25 cubic meters of air. (Even if his metabolism changed in the cold water, Umansky says, this is still a safe estimate). But Okene was breathing at 100 feet, or 30 meters, below the surface of the water. For every 10 meters a person descends, one atmosphere of pressure is added. This compresses gas and makes it denser, according to Boyle’s law.

Since Okene was trapped at 30 meters below the surface, his air supply became denser by a factor of four. This means he needed only 6 cubic meters of air to survive rather than 25 cubic meters. A space of about 6 feet by 10 feet by 3 feet would be sufficient to supply that amount of air. The press reported that Okene’s chamber was only about 4 feet high, and Umansky speculates that it must have been connected to another air pocket under the hull of the boat. “That’s the most reasonable explanation for this miraculous survival,” he said.

In a lively discussion on the physics forum, about a dozen participants offered their own calculations and observations. One user, Anna V., came up with a slightly larger figure for the bubble’s required size, about 10 feet by 25 feet by 25 feet. An enclosure of this size “is a reasonable one on a tugboat,” she writes. “He was just lucky the air siphoned where he was trapped.”

Other people have survived short periods underwater breathing trapped air. In 1991 diver Michael Proudfoot reportedly spent two days in an air pocket on a sunken ship off the coast of California after he accidentally smashed his scuba gear. Okene likely holds the new record for most time spent trapped underwater. After his rescue, he had to spend another 60 hours in a decompression chamber to rid his body of excess nitrogen, and some of his skin peeled off from soaking in salt water for so long. As one of his friends understatedly wrote on Okene’s Facebook wall, “I feel sorry for u that happened man.” Dozens of other friends and family members thank God and Jesus for looking out for Okene, though perhaps a hat tip to physics is in order, too.

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.