Tag: The Future

Radical plan proposed to re-freeze the Arctic

Physicist Steven Desch has come up with a novel solution to the problems that now beset the Arctic. He and a team of colleagues from Arizona State University want to replenish the region’s shrinking sea ice – by building 10 million wind-powered pumps over the Arctic ice cap. In winter, these would be used to pump water to the surface of the ice where it would freeze, thickening the cap.

The pumps could add an extra metre of sea ice to the Arctic’s current layer, Desch argues. The current cap rarely exceeds 2-3 metres in thickness and is being eroded constantly as the planet succumbs to climate change.

“Thicker ice would mean longer-lasting ice. In turn, that would mean the danger of all sea ice disappearing from the Arctic in summer would be reduced significantly,” Desch told the Observer.

Desch and his team have put forward the scheme in a paper that has just been published in Earth’s Future, the journal of the American Geophysical Union, and have worked out a price tag for the project: $500bn (£400bn).

It is an astonishing sum. However, it is the kind of outlay that may become necessary if we want to halt the calamity that faces the Arctic, says Desch, who, like many other scientists, has become alarmed at temperature change in the region. They say that it is now warming twice as fast as their climate models predicted only a few years ago and argue that the 2015 Paris agreement to limit global warming will be insufficient to prevent the region’s sea ice disappearing completely in summer, possibly by 2030.

“Our only strategy at present seems to be to tell people to stop burning fossil fuels,” says Desch. “It’s a good idea but it is going to need a lot more than that to stop the Arctic’s sea ice from disappearing.”

The loss of the Arctic’s summer sea ice cover would disrupt life in the region, endanger many of its species, from Arctic cod to polar bears, and destroy a pristine habitat. It would also trigger further warming of the planet by removing ice that reflects solar radiation back into space, disrupt weather patterns across the northern hemisphere and melt permafrost, releasing more carbon gases into the atmosphere.

Hence Desch’s scheme to use wind pumps to bring water that is insulated from the bitter Arctic cold to its icy surface, where it will freeze and thicken the ice cap. Nor is the physicist alone in his Arctic scheming: other projects to halt sea-ice loss include one to artificially whiten the Arctic by scattering light-coloured aerosol particles over it to reflect solar radiation back into space, and another to spray sea water into the atmosphere above the region to create clouds that would also reflect sunlight away from the surface.

All the projects are highly imaginative – and extremely costly. The fact that they are even being considered reveals just how desperately worried researchers have become about the Arctic. “The situation is causing grave concern,” says Professor Julienne Stroeve, of University College London. “It is now much more dire than even our worst case scenarios originally suggested.’

Last November, when sea ice should have begun thickening and spreading over the Arctic as winter set in, the region warmed up. Temperatures should have plummeted to -25C but reached several degrees above freezing instead. “It’s been about 20C warmer than normal over most of the Arctic Ocean. This is unprecedented,” research professor Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University told the Guardian in November. “These temperatures are literally off the charts for where they should be at this time of year. It is pretty shocking. The Arctic has been breaking records all year. It is exciting but also scary.”

Nor have things got better in the intervening months. Figures issued by the US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), in Boulder, Colorado, last week revealed that in January the Arctic’s sea ice covered 13.38 million sq km, the lowest January extent in the 38 years since satellites began surveying the region. That figure is 260,000 sq km below the level for January last year, which was the previous lowest extent for that month, and a worrying 1.26 million sq km below the long-term average for January.

In fact, sea ice growth stalled during the second week of January – in the heart of the Arctic winter – while the ice cap actually retreated within the Kara and Barents seas, and within the Sea of Okhotsk. Similarly, the Svalbard archipelago, normally shrouded in ice, has remained relatively free because of the inflow of warm Atlantic water along the western part of the island chain. Although there has been some recovery, sea ice remains well below all previous record lows.

This paucity of sea ice bodes ill for the Arctic’s summer months when cover traditionally drops to its lower annual level, and could plunge to a record minimum this year. Most scientists expect that, at current emission rates, the Arctic will be reliably free of sea ice in summer by 2030.

By “free” they mean there will be less than 1m sq km of sea ice left in the Arctic, most of it packed into remote bays and channels, while the central Arctic Ocean over the north pole will be completely open. And by “reliably”, scientists mean there will have been five consecutive years with less than 1m sq km of ice by the year 2050. The first single ice-free year will come much earlier than this, however.

And when that happens, the consequences are likely to be severe for the human and animal inhabitants of the region. An ice-free Arctic will be wide open to commercial exploitation, for example. Already, mining, oil and tourism companies have revealed plans to begin operations – schemes that could put severe strain on indigenous communities’ way of life in the region.

Equally worrying is the likely impact on wildlife, says Stroeve. “Juvenile Arctic cod like to hang out under the sea ice. Polar bears hunt on sea ice, and seals give birth on it. We have no idea what will happen when that lot disappears. In addition, there is the problem of increasing numbers of warm spells during which rain falls instead of snow. That rain then freezes on the ground and forms a hard coating that prevents reindeer and caribou from finding food under the snow.”

Nor would the rest of the world be isolated. With less ice to reflect solar radiation back into space, the dark ocean waters of the high latitudes will warm and the Arctic will heat up even further.

“If you warm the Arctic you decrease the temperature difference between the poles and the mid-latitudes, and that affects the polar vortex, the winds that blow between the mid latitudes and the high latitudes,” says Henry Burgess, head of the Arctic office of the UK Natural Environment Research Council.

“Normally this process tends to keep the cold in the high north and milder air in mid-latitudes but there is an increasing risk this will be disrupted as the temperature differential gets weaker. We may get more and more long, cold spells spilling down from the Arctic, longer and slower periods of Atlantic storms and equally warmer periods in the Arctic. What happens up there touches us all. It is hard to believe you can take away several million sq km of ice a few thousand kilometres to the north and not expect there will be an impact on weather patterns here in the UK.”

For her part, Stroeve puts it more bleakly: “We are carrying out a blind experiment on our planet whose outcome is almost impossible to guess.”

This point is backed by Desch. “Sea ice is disappearing from the Arctic – rapidly. The sorts of options we are proposing need to be researched and discussed now. If we are provocative and get people to think about this, that is good.

“The question is: do I think our project would work? Yes. I am confident it would. But we do need to put a realistic cost on these things. We cannot keep on just telling people, ‘Stop driving your car or it’s the end of the world’. We have to give them alternative options, though equally we need to price them.”

THE BIG SHRINK

The Arctic ice cap reaches its maximum extent every March and then, over the next six months, dwindles. The trough is reached around mid-September at the end of the melting season. The ice growth cycle then restarts. However, the extent of regrowth began slackening towards the end of the last century. According to meteorologists, the Arctic’s ice cover at its minimum is now decreasing by 13% every decade – a direct consequence of heating triggered by increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Climate change deniers claim this loss is matched by gains in sea ice around the Antarctic. It is not. Antarctic ice fluctuations are slight compared with the Arctic’s plummeting coverage and if you combine the changes at both poles, you find more than a million sq km of ice has been lost globally in 30 years.

Elon Musk: Humans must merge with machines or become irrelevant in AI age

by Arjun Kharpal

Billionaire Elon Musk is known for his futuristic ideas and his latest suggestion might just save us from being irrelevant as artificial intelligence (AI) grows more prominent.

The Tesla and SpaceX CEO said on Monday that humans need to merge with machines to become a sort of cyborg.

“Over time I think we will probably see a closer merger of biological intelligence and digital intelligence,” Musk told an audience at the World Government Summit in Dubai, where he also launched Tesla in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

“It’s mostly about the bandwidth, the speed of the connection between your brain and the digital version of yourself, particularly output.”

Musk explained what he meant by saying that computers can communicate at “a trillion bits per second”, while humans, whose main communication method is typing with their fingers via a mobile device, can do about 10 bits per second.

In an age when AI threatens to become widespread, humans would be useless, so there’s a need to merge with machines, according to Musk.

“Some high bandwidth interface to the brain will be something that helps achieve a symbiosis between human and machine intelligence and maybe solves the control problem and the usefulness problem,” Musk explained.

The technologists proposal would see a new layer of a brain able to access information quickly and tap into artificial intelligence. It’s not the first time Musk has spoken about the need for humans to evolve, but it’s a constant theme of his talks on how society can deal with the disruptive threat of AI.

‘Very quick’ disruption

During his talk, Musk touched upon his fear of “deep AI” which goes beyond driverless cars to what he called “artificial general intelligence”. This he described as AI that is “smarter than the smartest human on earth” and called it a “dangerous situation”.

While this might be some way off, the Tesla boss said the more immediate threat is how AI, particularly autonomous cars, which his own firm is developing, will displace jobs. He said the disruption to people whose job it is to drive will take place over the next 20 years, after which 12 to 15 percent of the global workforce will be unemployed.

“The most near term impact from a technology standpoint is autonomous cars … That is going to happen much faster than people realize and it’s going to be a great convenience,” Musk said.

“But there are many people whose jobs are to drive. In fact I think it might be the single largest employer of people … Driving in various forms. So we need to figure out new roles for what do those people do, but it will be very disruptive and very quick.”

An Uber Self-Driving Truck Just Took Off With 50,000 Beers

BY VANESSA BATES RAMIREZ

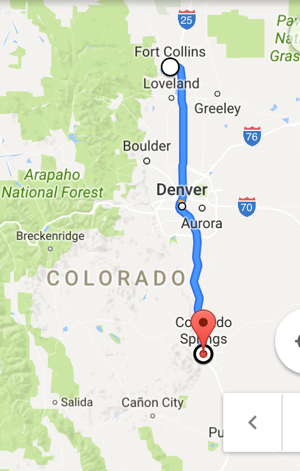

Drivers on Colorado’s interstate 25 may have gotten a good scare last Thursday, and it wasn’t a Halloween prank—glancing into the cab of an Otto 18-wheeler loaded with a beer delivery, they’d have been stunned to notice there was no one at the wheel.

In the first-ever commercial shipment completed using self-driving technology, the truck drove itself 120 miles from Fort Collins to Colorado Springs while its human driver sat in the sleeper cab. The driver did have control of the truck from departure until it got on the highway, and took over again when it was time to exit the highway.

Uber acquired Otto in August for $680 million. The company partnered with Anheuser-Busch for its first autonomous delivery, which consisted of 50,000 cans of beer—cargo many would consider highly valuable.

How the trucks work

Because of the relatively constant speed and less-dense surroundings, highway driving is much simpler for a driverless vehicle than city driving. There are no stop signs or pedestrians to worry about, and it’s not even necessary to change lanes if the delivery’s not on a tight schedule.

To switch from human driver to self-driving mode, all the driver had to do was press a button labeled “engage,” and this kicked the truck’s $30,000 of retro-fitted technology into action: there are three lidars mounted on the cab and trailer, a radar attached to the bumper, and a high-precision camera above the windshield.

The company made sure to plan the trip at a low-traffic time and on a day with clear weather, carefully studying the route to make sure there wouldn’t be any surprises the truck couldn’t handle along the way.

Why they’re disruptive

Though self-driving cars certainly get more hype than self-driving trucks do, self-driving truck are currently more necessary and could have an equally disruptive, if not larger, effect on the economy. Anheuser-Busch alone estimates it could save $50 million a year (and that’s just in the US) by deploying autonomous trucks across its distribution network.

Now extrapolate those savings over the entire trucking industry, extending the $50 million estimate to every company that delivers a similar volume of cargo throughout the US via trucks. The total easily leaps into the billions.

But what about all those jobs?

This doesn’t mean the company would fire all its drivers; savings would come from primarily from reduced fuel costs and a more efficient delivery schedule.

As of September 2016, the trucking industry employed around 1.5 million people, and 70 percent of cargo in the US is moved by trucks, with total freight tonnage predicted to grow 35% over the next ten years.

That’s a lot of freight. And as it turns out, the industry is sorely lacking in drivers to move it. The American Trucking Association estimates its current shortfall of drivers at 48,000. So rather than displacing jobs, autonomous trucking technology may actually help lift some of the burden off a tightly-stretched workforce.

Rather than pulling over to sleep when they get tired, drivers could simply time their breaks to coincide with long stretches of highway, essentially napping on the job and saving valuable time, not to mention getting their deliveries to their destinations faster.

In an interview with Bloomberg, Otto president and co-founder Lior Ron assured viewers that trucking jobs aren’t going anywhere anytime soon: “The future is really those drivers becoming more of a copilot to the technology, doing all the driving on city streets manually, then taking off onto the highway, where the technology can help drive those long and very cumbersome miles… for the foreseeable future, there’s a driver in the cabin and the driver is now safer, making more money, and can finish the route faster.”

Besides taking a load off drivers, self-driving trucks will likely make the roads far safer. According to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, about one in ten highway deaths occurs in a crash involving a large truck, and over 3,600 people were killed in large truck crashes in 2014.

The biggest culprit? Human error.

It’s not a done deal just yet

Otto’s trucks are considered to be in the Level 4 group of autonomous vehicles, which means human drivers are unnecessary in reasonably-controlled environments; on the highway, drivers can actually take a nap if they want to. In comparison, Tesla’s Autopilot system is considered Level 2, meaning it helps the driver by maintaining speed and avoiding obstacles, but the driver still needs to be engaged and paying close attention.

Besides the fact that the technology has a ways to go before being ready for large-scale deployment, barriers like regulation and plain old resistance to change could slow things down.

Drivers interviewed for a New York Times article were far from endorsing the co-pilot idea, due both to safety concerns and the degree to which self-driving technology would change the nature of their jobs.

If it were me, I know a whole lot of testing would have to be done before I’d be okay with falling asleep inside a vehicle moving at 60 miles an hour without a driver.

Once the technology’s been proven to a fail-proof rate, however, truckers may slowly adapt to the idea of being able to drive 1,200 miles in the time it used to take to drive 800.

The world’s knowledge is being buried in a salt mine: the Memory of Mankind project

By Richard Gray

Etched with strange pictograms, lines and wedge-shaped markings, they lay buried in the dusty desert earth of Iraq for thousands of years. The clay tablets left by the ancient Sumerians around 5,000 years ago provide what are thought to be the earliest written record of a long dead people.

Although it took decades for archaeologists to decipher the mysterious language preserved on the slabs, they have provided glimpses of what life was like at the dawn of civilisation.

Similar tablets and carved stones have been unearthed at the sites of other mighty cultures that have long since vanished – from the hieroglyphics of the Ancient Egyptians to the inscriptions of the Maya of Mesoamerica.

The stories and details they contain have stood the test of time, surviving through the millennia to be unearthed and deciphered by modern historians. But there are fears that future archaeologists may not benefit from the same sort of immutable record when they come to search for evidence of our own civilisation. We live in a digital world where information is stored as lists of tiny electronic ones and zeros that can be edited or even wiped clean by a few accidental strokes on a keyboard. “Unfortunately we live in an age that will leave hardly any written traces,” explained Martin Kunze.

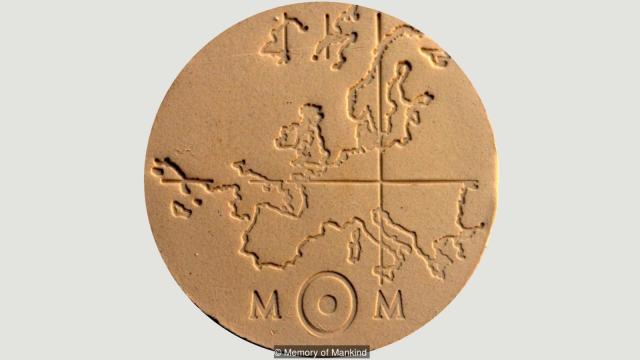

Kunze’s solution is the Memory of Mankind project, a collaboration between academics, universities, newspapers and libraries to create a modern version of those first ancient Sumerian tablets discovered in the desert. Their plan is to gather together the accumulated knowledge of our time and store it underground in the caverns carved out in one of the oldest salt mines in the world, in the mountains of Austria’s picturesque Salzkammergut. “The main point of what we are doing is to store information in a way that it is readable in the future. It is a backup of our knowledge, our history and our stories,” says Kunze.

Creating a stone “time capsule” may seem archaic in the age where most of our knowledge now floats around the internet cloud, but a slide back into the technological dark ages is not beyond comprehension. The advent of the internet has seen people have more information at their fingertips than at any previous point in human history. Yet the huge repositories of knowledge we have built up are perilously vulnerable.

Ever more information is being stored digitally on remote computer servers and hard disks. How many of us have hard copies of the photographs we took on our last holiday, for example.

The situation gets more serious when we consider scientific papers that are now solely published online. Entire catalogues of video footage from news broadcasters, television and film are stored digitally. Official documents and government papers reside in digital libraries.

Yet a conference of space weather scientists, together with officials from Nasa and the US Government, earlier this year warned of the fragile nature of all this digital information. Charged particles thrown out by the sun in a powerful solar storm could trigger electromagnetic surges that could render our electronic devices useless and wipe data stored in memory drives.

Such storms are a real threat, and they happen relatively regularly. A report produced by the British Government last year highlighted that severe solar storms appear to happen every 100 years.

The last major coronal mass ejection to hit the Earth, known as the Carrington event, was in 1859 and is thought to have been the biggest in 500 years. It blew telegraph systems all over the world and pylons threw sparks. In the age of the internet, such an event would be catastrophic.

But there are other threats too – malicious hackers or even careless officials could tamper with these digital records or delete them altogether. And what if we simply lose the ability to read this information? Technology is changing so fast that media formats are quickly rendered obsolete. Minidiscs, VHS and the humble floppy disk have become outdated within decades.

Few computers even come with DVD drives now, while giving the current generation of teenagers a floppy disk would leave them flummoxed. If information is stored on one of these formats and the technology needed to access it disappears completely, then it could be lost forever.

Hence the desire to keep a hard copy of our most important documents. Unfortunately, even the more traditional forms of storing information are also unlikely to keep information safe for more than a few centuries. While we have some paper manuscripts that have survived for hundreds of years – and in the case of papyrus scrolls, for thousands – unless they are stored in the right conditions, most disintegrate to dust after a couple of hundred years. Newspaper can decompose within six weeks if it gets wet.

“It is very likely that in the long term the only traces of our present activities will be global warming, nuclear waste and Red Bull cans,” says Kunze. “The amount of data is inflating rapidly, so the real challenge becomes selecting what we want to keep for our grandchildren and those that come after them.”

Which is why Kunze and his colleagues are instead looking further back in time for inspiration, to those Sumerian stone tablets. The Memory of Mankind team hopes to create an indelible record of our way of life by imprinting official documents, details about our culture, scientific papers, biographies, popular novels, news stories and even images onto square ceramic plates measuring eight inches (20cm) across.

This hinges on a special process that Kunze describes as “ceramic microfilm”, which he says is the most durable data storage system in the world. The flat ceramic plates are covered with a dark coating and a high energy laser is then used to write into them.

Each of these tablets can hold up to five million characters – about the same as a four-hundred-page book. They are acid- and alkali-resistant and can withstand temperatures of 1300C. A second type of tablet can carry colour pictures and diagrams along with 50,000 characters before being sealed with a transparent glaze.

The plates are then stacked inside ceramic boxes and tucked into the dark caverns of a salt mine in Hallstatt, Austria. As a resting place for what could be described as the ultimate time capsule, it is impressive. In the right light the walls still glisten with the remnants of salt, which extracts moisture and desiccates the air.

The salt itself has a Plasticine-like property that helps to seal fractures and cracks, keeping the tomb watertight. Buried beneath millions of tonnes of rock, the records will be able to survive for millennia and perhaps even entire ice ages, Kunze believes.

In some distant future after our own civilisation has vanished, they could prove invaluable to any who find them. They could help resurrect forgotten knowledge for cultures less advanced than our own, or provide a wealth of historical information for more advanced civilisations to ensure our own achievements, and our mistakes, can be learned from.

But it could also have value in the shorter term too.

“We are trying to create something that will not only be a collection of information for a distant future, but it will also be a gift for our grandchildren,” says Kunze. “Memory of Mankind can serve as a backup of knowledge in case of an event like war, a pandemic or a meteorite that throws us back centuries within two or three generations. A society can lose skills and knowledge very quickly – in the 6th Century, Europe largely lost the ability to read and write within three generations.”

Already the Memory of Mankind archive contains an eclectic glimpse of our society. Among the information etched into the ceramic plates are books summarising the history of individual countries around the world. Towns and villages have also opted to include their own local histories. A thousand of the world’s most important books – chosen by combining published lists using an algorithm developed by the University of Vienna – will be cut into the coating on the ceramic plates.

Museums are including images of precious objects in their collections along with descriptions of what we have learned about them. The Krumau Madonna – a sculpture dating to the late 14th Century currently sitting in the Museum of Art History in Vienna – is already there, along with paintings by the Baroque artists Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck.

There are plates featuring pictures of fossils – dinosaurs, prehistoric fish and extinct ammonites – alongside a description of what we know about them. Even our current understanding of our own origins are included, with pictures of one of the earliest examples of sculpture ever found – the Venus of Willendorf.

Much of the material included on the tablets is in German, but there are tablets in English, French and other languages.

A handful of celebrities have also found themselves immortalised in the salt-lined vaults. Baywatch star and singer David Hasselhoff has a particularly lengthy entry as does German singer Nena who had a hit with 99 Red Balloons in the 1980s. Nestled among them is a plate detailing the story of Edward Snowden and his leak of classified material from the US National Security Agency.

The University of Vienna has been placing prize winning PhD dissertations and scientific papers onto the tablets. Included in the archive are plates describing genetic modification and bioengineering patents, explaining what today’s scientists have achieved and how they managed it.

And alongside research, everyday objects like washing machines, smartphones and televisions are also being documented as a record of what life is like today.

The plates also serve as a warning for future generations – with sites of nuclear waste dumps pinpointed so future generations might know to avoid them or to clean them up if they have the technology. Newspapers have been asked to send their daily editorials to provide a repository of opinions as well as facts.

In many ways, the real problem is what not to include. “We probably have about 0.1% of the antique literature yet in the modern world publishing is as easy as posting something on the internet or sending a tweet,” explains Kunze. “Publications about science, space flight and medicine – the things we really spend money on – drown in the mass of data we produce. The Large Hadron Collider produces something like 30 Petabytes of data a year, but this is equal to just 0.003% of annual internet traffic. “A random fragment of 0.1% of our present day data will result in a very distorted view of our time.”

To tackle this, Kunze and his colleagues are organising a conference in November next year to bring scientists, historians, archaeologists, linguists and philosophers together to create a blueprint for selecting content for the project. The team also hope to immortalise glimpses of mundane, everyday life as members of the public are encouraged to create tablets of their own. “We are saving cooking recipes and stories of love and personal events,” adds Kunze. “On one plate, a little girl has included three photographs of her confirmation and written a short bit of text about it. They give a glimpse of everyday life that will be very valuable.”

Preserved tweets

Memory of Mankind is not the only project to face the daunting task of preserving humanity’s accumulated knowledge. Librarians around the world are also looking at the knotty problem of how to save the information from the modern age.

The University of California Los Angeles, for instance, is archiving tweets related to major events and preserving them in their own archives. “We are collecting tweets from Cairo on the day of the January 25th revolution for example,” explained Todd Grappone, associate university librarian. “We are then translating them into multiple languages and saving them in file formats that are likely to be robust for the future. We are only doing it digitally at the moment as we have something like 1,000 cellphone videos from that event alone, but the value of that is enormous.”

Another project, called the Human Document Project, is aiming to record information on wafers of tungsten/silicon nitride. Initially they have been etching them with dozens of tiny QR codes – a type of two-dimensional barcode – which can be read using smartphones, but they say the final disks will hold information written in a form that can be read using a microscope.

Leon Abelmann, a researcher at Twente University in Enschede, the Netherlands, is one of the driving forces behind the project. He says that they are hoping to produce something that will be able to survive for one million years and are now starting to collaborate with the Memory of Mankind. “We would be really happy if we found information left for us by an intelligence that has already been extinct for a million years,” he said. “So we think future intelligent beings will be too. The mere fact that we need to take a helicopter view of ourselves will hopefully make us realise that the differences between us are trivial.”

Buried under a mountain, it may seem unlikely that any future generations would be able to find these tablets. For this reason, Memory of Mankind will has engraved some small tokens with a map pinpointing the archives’ location, which they will then bury at strategic places around the world. Other tokens are being entrusted to 50 holders who will pass them onto the next generation.

To ensure those who do find it can actually read what is in there, the Memory of Mankind team has been creating their own Rosetta Stone – thousands of images labelled with their names and meanings.

All of which gives a hint at the ambition of what they are trying to do. The individuals who unearth this gold-mine of knowledge could be very different from our own. In a few thousand years civilisation may have advanced beyond our reckoning or descended back to the dark ages. Perhaps it will not even be humans who end up uncovering our memories. “We could be looking at some other form of intelligent life,” adds Kunze.

We will never know what those future archaeologists will make of our civilisation when they wipe the dust away from the tablets in thousands of years’ time, but we can hope that like the ancient Sumarians, we will not be forgotten.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20161018-the-worlds-knowledge-is-being-buried-in-a-salt-mine

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the It’s Interesting community.

New advances in quantum artificial intelligence could lead to super-smart machines

by Bryan Nelson

Quantum physics has some spooky, anti-intuitive effects, but it could also be essential to how actual intuition works, at least in regards to artificial intelligence.

In a new study, researcher Vedran Dunjko and co-authors applied a quantum analysis to a field within artificial intelligence called reinforcement learning, which deals with how to program a machine to make appropriate choices to maximize a cumulative reward. The field is surprisingly complex and must take into account everything from game theory to information theory.

Dunjko and his team found that quantum effects, when applied to reinforcement learning in artificial intelligence systems, could provide quadratic improvements in learning efficiency, reports Phys.org. Exponential improvements might even be possible over short-term performance tasks. The study was published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

“This is, to our knowledge, the first work which shows that quantum improvements are possible in more general, interactive learning tasks,” explained Dunjko. “Thus, it opens up a new frontier of research in quantum machine learning.”

One of the key quantum effects in regards to learning is quantum superposition, which potentially allows a machine to perform many steps simultaneously. Such a system has vastly improved processing power, which allows it to compute more variables when making decisions.

The research is tantalizing, in part because it mirrors some theories about how biological brains might produce higher cognitive states, possibly even being related to consciousness. For instance, some scientists have proposed the idea that our brains pull off their complex calculations by making use of quantum computation.

Could quantum effects unlock consciousness in our machines? Quantum physics isn’t likely to produce HAL from “2001: A Space Odyssey” right away; the most immediate improvements in artificial intelligence will likely come in complex fields such as climate modeling or automated cars. But eventually, who knows?

You probably won’t want to be taking a joyride in an automated vehicle the moment it becomes conscious, if HAL is an example of what to expect.

“While the initial results are very encouraging, we have only begun to investigate the potential of quantum machine learning,” said Dunjko. “We plan on furthering our understanding of how quantum effects can aid in aspects of machine learning in an increasingly more general learning setting. One of the open questions we are interested in is whether quantum effects can play an instrumental role in the design of true artificial intelligence.”

Ford Promises Fleets of Driverless Cars Within Five Years

“Autonomous vehicles could have just as much significant impact on society as Ford’s moving assembly line did 100 years ago,” said Mark Fields, chief executive of Ford.

by NEAL E. BOUDETTE

In the race to develop driverless cars, several automakers and technology companies are already testing vehicles that pilot themselves on public roads. And others have outlined plans to expand their development fleets over the next few years.

But few have gone so far as to give a definitive date for the commercial debut of these cars of the future.

Now Ford Motor has done just that.

At a news conference on Tuesday at the company’s research center in Palo Alto, Calif., Mark Fields, Ford’s chief executive, said the company planned to mass produce driverless cars and have them in commercial operation in a ride-hailing service by 2021.

Beyond that, Mr. Fields’s announcement was short on specifics. But he said that the vehicles Ford envisioned would be radically different from those that populate American roads now.

“That means there’s going to be no steering wheel. There’s going to be no gas pedal. There’s going to be no brake pedal,’’ he said. “If someone had told you 10 years ago, or even five years ago, that the C.E.O. of a major automaker American car company is going to be announcing the mass production of fully autonomous vehicles, they would have been called crazy or nuts or both.”

The company also said on Tuesday that as part of the effort, it planned to expand its Palo Alto center, doubling the number of employees who work there over the next year, from the current 130.

Ford also said it had acquired an Israeli start-up, Saips, that specializes in computer vision, a crucial technology for self-driving cars. And the automaker announced investments in three other companies involved in major technologies for driverless vehicles.

For several years, automakers have understood that their industry is being reshaped by the use of advanced computer chips, software and sensors to develop cars designed to drive themselves. The tech companies Google and Apple have emerged as potential future competitors to automakers, while Tesla Motors has already proved a competitive threat to luxury brands like BMW and Mercedes-Benz with driver-assistance and collision-avoidance technologies.

More recently, ride-sharing service providers like Uber have raised the competitive concerns of the conventional auto industry. The ride-hailing services aim to operate fleets of driverless cars that, in the future, might provide ready transportation to anyone, making it easier for people to get around without owning a car or even having a driver’s license

A Barclays analyst, Brian Johnson, recently predicted that once autonomous vehicles are in widespread use, auto sales could fall as much as 40 percent as people rely on such services for transportation and choose not to own cars.

Mr. Fields said on Tuesday that the combination of driverless cars and ride-sharing services represented a “seismic shift” for the auto industry that would be greater than the advent of the moving production line was roughly a century ago.

“The world is changing, and it’s changing rapidly,” he said, adding that Ford now sees itself as not just a carmaker but a “mobility company.”

BMW and Mercedes-Benz are among the carmakers that have seized upon the concept of “transportation as a service,” as it is called, by starting ride-sharing services of their own. General Motors has teamed up with, and bought a stake in, Lyft, the main rival of Uber.

GM and Lyft plan to have driverless vehicles operating in tests within a year. Initially, at least, those tests will be conducted with a driver in the car to take control from the self-driving technology, if necessary.

Even some auto suppliers are focusing on ride-hailing services and driverless cars. This month, the components maker Delphi announced that it was working with the government of Singapore to develop a ride service to shuttle people to and from mass transit stations in the country’s business district.

Even though Ford has committed itself to a date for a commercial introduction of its driverless cars, several questions remain about how it will move forward, said Michelle Krebs, an analyst with AutoTrader.

For example, Ford does not have a ride-sharing partner as G.M. does in Lyft, Ms. Krebs said.

In a research note on Tuesday, Mr. Johnson noted that it remained unclear how auto companies would make money from ride-sharing services.

“These are a lot of promises, but we don’t yet know how they are going to evolve,” Ms. Krebs said. “There are still missing pieces.”

One of the investments Ford announced on Tuesday was a $75 million stake in Velodyne, which makes sensors that use lidar, a kind of radar based on laser beams. The Chinese internet company Baidu said it was making a comparable investment in Velodyne.

Ford also said it had made investments in Nirenberg Neuroscience, which is also developing machine vision technology, and Civil Maps, a start-up that is developing 3D digital maps for use by automated vehicles. Ford did not disclose the amount it invested in Nirenberg or Civil Maps.

Can the World Sustain 9 Billion People by 2050?

By Philip Perry

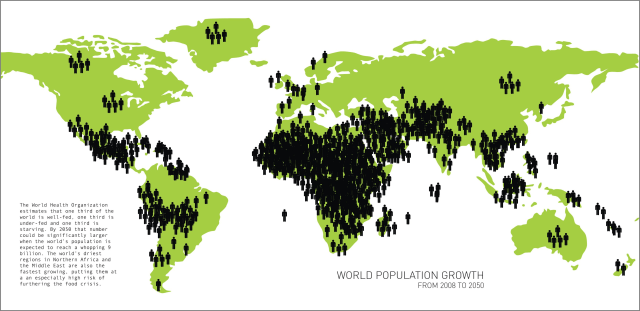

The world’s population is topsy-turvy, and its exponential and uneven growth could have disastrous consequences if we aren’t ready for it. Humanity recently hit a benchmark, a population of 7.9 billion in 2013. It is expected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030, and 9.6 billion by 2050. If that weren’t enough, consider 11.2 billion in 2100. Most of the growth is supposed to come from nine specific countries: India, Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Nigeria, the United States, and Indonesia.

It isn’t fertility that is driving growth, but rather longer lifespans. World population growth peaked in the 1960s, and has been dropping steadily since the ’70s. 1.24% was the growth rate a decade ago, annually. Today, it is 1.18% per year. Populations in developed countries have slowed to a trickle. Here, it has gotten too expensive to have a child for a large segment of the populace, particularly in the wake of the Great Recession, when young people have to invest a lot of time in education and building a career, spending their most fertile years in lecture halls and office cubicles. Although overall, fertility has been dropping worldwide, the report says researchers used the “low-variant” scenario of population growth. It could be higher.

World population growth by continent.

Meanwhile, the enormous baby boomer generation is aging, and public health officials warn that a “Silver Tsunami” is coming. Worldwide, those age 60 and over are expected to double by 2050, and triple by 2100. As workers age, fewer young people are around to replace them, and that means less taxpayers for Medicare and abroad, for socialized medicine. In Europe, a staggering 34% of the population is projected to be over 60 by 2050. What’s more, Europe’s population is forecast to plummet 14%. It is already struggling, as is Japan, to provide for its aging population. But the birth deficit is likely to exacerbate the problem.

In the U.S., the number of Alzheimer’s patients alone is expected to bankrupt Medicare, if no cure is found, and the program remains as it is today. “Developed countries have largely painted themselves into a corner now,” according to Carl Haub. He is the senior demographer at the Population Reference Bureau.

According to a U.N. report, most of the growth will come from developing countries, with over half projected to take place in Africa, the poorest continent financially, whose resources are already under pressure. 15 highly fertile countries, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa, are expected to increase the number of children per woman at a rate of a little over five per cent, or five per female. Nigeria’s population will likely surpass that of the U.S. by 2050, becoming the third largest in terms of demographics.

The population in developed countries is expected to remain unchanged, holding steady at 1.3 billion. Some developing countries such as Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia, India, and China are seeing a swift fall in the average number of children per woman, which is expected to continue. This may be due to better economic prospects. We often think of China as the world’s most populous nation, but India is set to reach them by 2022, when both nations will contain 1.45 billion citizens. Afterward, India is predicted to surpass China. As India’s population grows, China’s will shrink.

As far as life expectancy, it is expected to increase in both developed and developing nations. Globally, life expectancy will likely be 76 years on average in the 2045-2050 period. It will reach 82 years of age in 2095-2100, if nothing changes. Nearing the end of the century, those in developing nations could expect to live to 81, while in developed nations, 89 will be the norm. Yet, there are concerns that the developing world will suffer even more than today due to this phenomenon.

“The concentration of population growth in the poorest countries presents its own set of challenges, making it more difficult to eradicate poverty and inequality, to combat hunger and malnutrition, and to expand educational enrollment and health systems,” according to John Wilmoth. He is the Director of the Population Division in the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Another worry is resource depletion. Minerals, fossil fuels, timber, and water may become scarce in several regions of the world. Since wars are often fought over resources, and water use is expected to increase 70-90% by mid-century, without improved farming methods and smarter use, water may become the next oil, in terms of driving nations into violent conflict. The world’s water in certain regions is already strained. India and China for instance have already fought two wars over water claims.

Climate change is also likely to eat up more arable land, contributing to fears of food scarcity, as well as the loss of biodiversity, which is likely to occur at a faster rate. To help tamp down the world population, UN researchers suggest investing in reproductive health and family planning, particularly in developing nations.

This report was made possible by 233 countries providing demographic data, as well as 2010 population censuses.

Smallest hard disk to date writes information atom by atom

Every day, modern society creates more than a billion gigabytes of new data. To store all this data, it is increasingly important that each single bit occupies as little space as possible. A team of scientists at the Kavli Institute of Nanoscience at Delft University managed to bring this reduction to the ultimate limit: they built a memory of 1 kilobyte (8,000 bits), where each bit is represented by the position of one single chlorine atom.

“In theory, this storage density would allow all books ever created by humans to be written on a single post stamp”, says lead-scientist Sander Otte.

They reached a storage density of 500 Terabits per square inch (Tbpsi), 500 times better than the best commercial hard disk currently available. His team reports on this memory in Nature Nanotechnology on Monday July 18.

Feynman

In 1959, physicist Richard Feynman challenged his colleagues to engineer the world at the smallest possible scale. In his famous lecture There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom, he speculated that if we had a platform allowing us to arrange individual atoms in an exact orderly pattern, it would be possible to store one piece of information per atom. To honor the visionary Feynman, Otte and his team now coded a section of Feynman’s lecture on an area 100 nanometers wide.

Sliding puzzle

The team used a scanning tunneling microscope (STM), in which a sharp needle probes the atoms of a surface, one by one. With these probes scientists cannot only see the atoms but they can also use them to push the atoms around. “You could compare it to a sliding puzzle”, Otte explains. “Every bit consists of two positions on a surface of copper atoms, and one chlorine atom that we can slide back and forth between these two positions. If the chlorine atom is in the top position, there is a hole beneath it — we call this a 1. If the hole is in the top position and the chlorine atom is therefore on the bottom, then the bit is a 0.” Because the chlorine atoms are surrounded by other chlorine atoms, except near the holes, they keep each other in place. That is why this method with holes is much more stable than methods with loose atoms and more suitable for data storage.

Codes

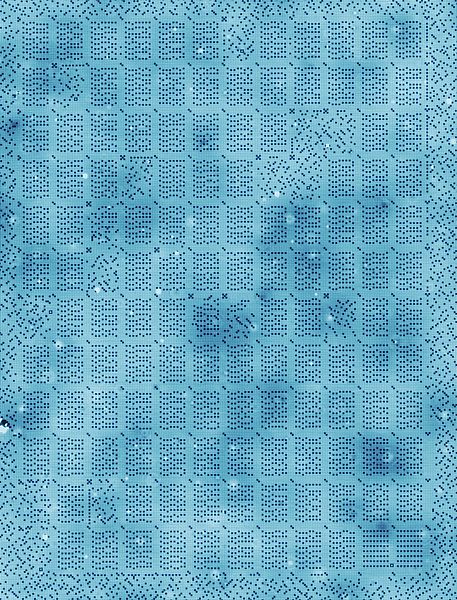

The researchers from Delft organized their memory in blocks of 8 bytes (64 bits). Each block has a marker, made of the same type of ‘holes’ as the raster of chlorine atoms. Inspired by the pixelated square barcodes (QR codes) often used to scan tickets for airplanes and concerts, these markers work like miniature QR codes that carry information about the precise location of the block on the copper layer. The code will also indicate if a block is damaged, for instance due to some local contaminant or an error in the surface. This allows the memory to be scaled up easily to very big sizes, even if the copper surface is not entirely perfect.

Datacenters

The new approach offers excellent prospects in terms of stability and scalability. Still, this type of memory should not be expected in datacenters soon. Otte: “In its current form the memory can operate only in very clean vacuum conditions and at liquid nitrogen temperature (77 K), so the actual storage of data on an atomic scale is still some way off. But through this achievement we have certainly come a big step closer”.

This research was made possible through support from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NOW/FOM). Scientists of the International Iberian Nanotechnology Laboratory (INL) in Portugal performed calculations on the behavior of the chlorine atoms.

For more information, please contact dr. Sander Otte, Kavli Institute of Nanoscience, TU Delft: A.F.Otte@tudelft.nl, +31 15 278 8998

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the It’s Interesting community.

Creating a Synthetic Human Genome

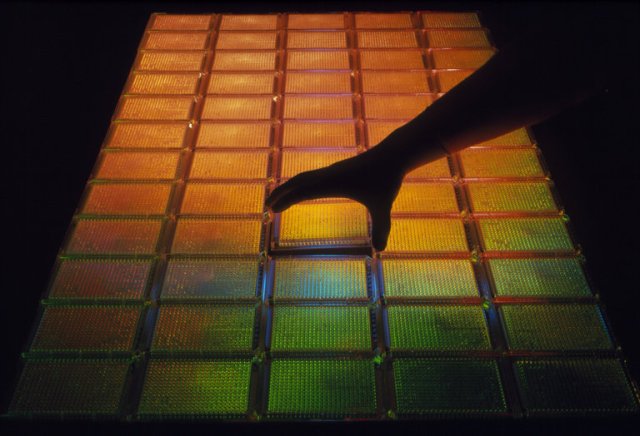

Sixty trays can contain the entire human genome as 23,040 different fragments of cloned DNA. Credit James King-Holmes/Science Source

By ANDREW POLLACK

Scientists are now contemplating the fabrication of a human genome, meaning they would use chemicals to manufacture all the DNA contained in human chromosomes.

The prospect is spurring both intrigue and concern in the life sciences community because it might be possible, such as through cloning, to use a synthetic genome to create human beings without biological parents.

While the project is still in the idea phase, and also involves efforts to improve DNA synthesis in general.

Organizers said the project could have a big scientific payoff and would be a follow-up to the original Human Genome Project, which was aimed at reading the sequence of the three billion chemical letters in the DNA blueprint of human life. The new project, by contrast, would involve not reading, but rather writing the human genome — synthesizing all three billion units from chemicals.

But such an attempt would raise numerous ethical issues. Could scientists create humans with certain kinds of traits, perhaps people born and bred to be soldiers? Or might it be possible to make copies of specific people?

“Would it be O.K., for example, to sequence and then synthesize Einstein’s genome?” Drew Endy, a bioengineer at Stanford, and Laurie Zoloth, a bioethicist at Northwestern University, wrote in an essay criticizing the proposed project. “If so how many Einstein genomes should be made and installed in cells, and who would get to make them?”

The project was initially called HGP2: The Human Genome Synthesis Project, with HGP referring to the Human Genome Project. An invitation to the meeting at Harvard said that the primary goal “would be to synthesize a complete human genome in a cell line within a period of 10 years.”

But by the time the meeting was held, the name had been changed to “HGP-Write: Testing Large Synthetic Genomes in Cells.”

The project does not yet have funding, Dr. Church said, though various companies and foundations would be invited to contribute, and some have indicated interest. The federal government will also be asked. A spokeswoman for the National Institutes of Health declined to comment, saying the project was in too early a stage.

Besides Dr. Church, the organizers include Jef Boeke, director of the institute for systems genetics at NYU Langone Medical Center, and Andrew Hessel, a self-described futurist who works at the Bay Area software company Autodesk and who first proposed such a project in 2012.

Scientists and companies can now change the DNA in cells, for example, by adding foreign genes or changing the letters in the existing genes. This technique is routinely used to make drugs, such as insulin for diabetes, inside genetically modified cells, as well as to make genetically modified crops. And scientists are now debating the ethics of new technology that might allow genetic changes to be made in embryos.

But synthesizing a gene, or an entire genome, would provide the opportunity to make even more extensive changes in DNA.

For instance, companies are now using organisms like yeast to make complex chemicals, like flavorings and fragrances. That requires adding not just one gene to the yeast, like to make insulin, but numerous genes in order to create an entire chemical production process within the cell. With that much tinkering needed, it can be easier to synthesize the DNA from scratch.

Right now, synthesizing DNA is difficult and error-prone. Existing techniques can reliably make strands that are only about 200 base pairs long, with the base pairs being the chemical units in DNA. A single gene can be hundreds or thousands of base pairs long. To synthesize one of those, multiple 200-unit segments have to be spliced together.

But the cost and capabilities are rapidly improving. Dr. Endy of Stanford, who is a co-founder of a DNA synthesis company called Gen9, said the cost of synthesizing genes has plummeted from $4 per base pair in 2003 to 3 cents now. But even at that rate, the cost for three billion letters would be $90 million. He said if costs continued to decline at the same pace, that figure could reach $100,000 in 20 years.

J. Craig Venter, the genetic scientist, synthesized a bacterial genome consisting of about a million base pairs. The synthetic genome was inserted into a cell and took control of that cell. While his first synthetic genome was mainly a copy of an existing genome, Dr. Venter and colleagues this year synthesized a more original bacterial genome, about 500,000 base pairs long.

Dr. Boeke is leading an international consortium that is synthesizing the genome of yeast, which consists of about 12 million base pairs. The scientists are making changes, such as deleting stretches of DNA that do not have any function, in an attempt to make a more streamlined and stable genome.

But the human genome is more than 200 times as large as that of yeast and it is not clear if such a synthesis would be feasible.

Jeremy Minshull, chief executive of DNA2.0, a DNA synthesis company, questioned if the effort would be worth it.

“Our ability to understand what to build is so far behind what we can build,” said Dr. Minshull, who was invited to the meeting at Harvard but did not attend. “I just don’t think that being able to make more and more and more and cheaper and cheaper and cheaper is going to get us the understanding we need.”