By Helen Thomson

What would you do if you had 60 days of extra free time a year? Ask Abby Ross, a retired psychologist from Miami, Florida, a “short-sleeper”. She needs only four hours sleep a night, so has a lot of spare time to fill while the rest of the world is in the land of nod.

“It’s wonderful to have so many hours in my day – I feel like I can live two lives,” she says.

Short-sleepers like Ross never feel lethargic, nor do they ever sleep in. They wake early – normally around four or five o’clock – raring to get on with their day. Margaret Thatcher may have been one – she famously said she needed just four hours a night, whereas Mariah Carey claims she needs 15.

What makes some people fantastically efficient sleepers, while others spend half their day snoozing? And can we change our sleeping pattern to make it more efficient?

In 2009, a woman came into Ying-Hui Fu’s lab at the University of California, San Francisco, complaining that she always woke up too early. At first, Fu thought the woman was an extreme morning lark – a person who goes to bed early and wakes early. However, the woman explained that she actually went to bed around midnight and woke at 4am feeling completely alert. It was the same for several members of her family, she said.

Fu and her colleagues compared the genome of different family members. They discovered a tiny mutation in a gene called DEC2 that was present in those who were short-sleepers, but not in members of the family who had normal length sleep, nor in 250 unrelated volunteers.

When the team bred mice to express this same mutation, the rodents also slept less but performed just as well as regular mice when given physical and cognitive tasks.

Getting too little sleep normally has a significant impact on health, quality of life and life expectancy. It can cause depression, weight gain and put you at greater risk of stroke and diabetes. “Sleep is so important, if you sleep well you can avoid many diseases, even dementia,” says Fu. “If you deprive someone of just two hours sleep a day, their cognitive functions become significantly impaired almost immediately.”

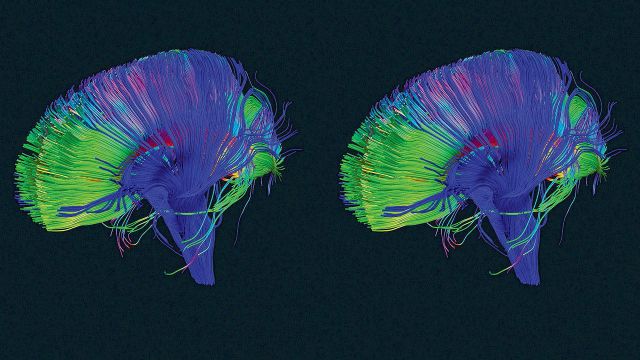

But why sleep is so important is still a bit of a mystery. The general consensus is that the brain needs sleep to do some housekeeping and general maintenance, since it doesn’t get much downtime during the day. While we sleep, the brain can repair cellular damage, remove toxins that accumulate during the day, boost flagging energy supplies and lay down memories.

“Clearly people with the DEC2 mutation can do the same cleaning up process in a shorter period of time – they are just more efficient than the rest of us at sleeping,” says Fu. “But how are they doing that? That’s the key question.”

Since discovering the DEC2 mutation, a lot of people have come forward claiming to only sleep a few hours a day, says Fu. Most of these had insomnia, she says. “We’re not focusing on those people who have sleeping issues that make them sleep less, we wanted to focus on people who sleep for a few hours and feel great.”

A positive outlook is common among all of the short-sleepers that Fu has studied. “Anecdotally,” she says, “they are all very energetic, very optimistic. It’s very common for them to feel like they want to cram as much into life as they can, but we’re not sure how or whether this is related to their mutations.”

Ross would seem to fit that mould. “I always feel great when I wake up,” she says. She has been living on four to five hours sleep every day for as long as she can remember.

“Those hours in the morning – around five o’clock – are just fabulous. It’s so peaceful and quiet and you can get so much done. I wish more shops were open at that time, but I can shop online, or I can read – oh there’s so much to read in this world! Or I can go out and exercise before anyone else is up, or talk to people in other time zones.”

Her short sleeping patterns allowed her to complete university in two and a half years, as well as affording her time to learn lots of new skills. For example, just three weeks after giving birth to her first son, Ross decided to use one of her early mornings to attempt to run around the block. It took her 10 minutes. The following day she did it again, running a little further. She slowly increased the time she ran, finally completing not one, but 37 marathons – one a month over three years – plus several ultramarathons. “I can get up and do my exercise before anyone else is up and then it’s done, out of the way,” she says.

As a child, Ross remembers spending very early mornings with her dad, another short-sleeper. “Our early mornings gave us such a special time together,” she says. Now, if she ever oversleeps – which she says has only ever happened a handful of times, her husband thinks she’s dead. “I just don’t lay in, I’d feel terrible if I did,” she says.

Fu has subsequently sequenced the genomes of several other families who fit the criteria of short-sleepers. They’re only just beginning to understand the gene mutations that lead to this talent, but in principle, she says, it might one day be possible to enable short sleeping in others.

Until then, are there any shortcuts to a more efficient night’s sleep for the rest of us? Neil Stanley, an independent sleep consultant, says yes: “The most effective way to improve your sleep is to fix your wake-up time in the morning.”

Stanley says that when your body gets used to the time it needs to wake up, it can use the time it has to sleep as efficiently as possible. “Studies show that your body prepares to wake up one and a half hours prior to actually waking up. Your body craves regularity, so if you chop and change your sleep pattern, your body hasn’t got a clue when it should prepare to wake up or not.”

You could also do yourself a favour by ignoring society’s views on sleep, he says. “There’s this social view that short sleeping is a good thing and should be encouraged – we’re always hauling out the example of Margaret Thatcher and top CEOs who don’t need much sleep. In fact, the amount of sleep you need is genetically determined as much as your height or shoe size. Some people need very little sleep, others need 11 or 12 hours to feel their best.”

Stanley says that a lot of people with sleep issues actually don’t have any problem sleeping, instead they have an expectation that they need to sleep for a certain amount of time. “If we could all figure out what kind of sleeper we are, and live our life accordingly, that would make a huge difference to our quality of life,” he says.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20150706-the-woman-who-barely-sleeps