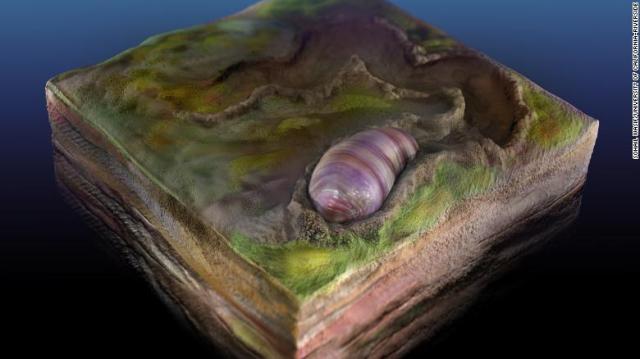

Evidence of a worm-like creature about the size of a grain of rice has been uncovered in South Australia, and researchers believe it is the oldest ancestor on the family tree that includes humans and most animals.

The creature lived 555 million years ago.

It’s considered to be the earliest bilaterian. Bilaterians are organisms with a front, back, two openings on either end and a gut that connects them. They were an evolutionary step forward for early life on Earth.

Some of the oldest life on Earth, including those sponges and algal mats, is referred to as the Ediacaran Biota. This group is based on the earliest fossils ever discovered, providing evidence of complex, multicellular organisms.

But those aren’t directly related to animals living today. And researchers have been trying to find fossilized evidence of the common ancestor of most animals.

Developing bilaterian body structure and organization successfully allowed life to move in specific, purposeful directions. This includes everything from worms and dinosaurs to amphibians and humans.

But for our common ancestor, they knew that fossils of the tiny, simple creatures they imagined would be nearly impossible to find because of its size and soft body.

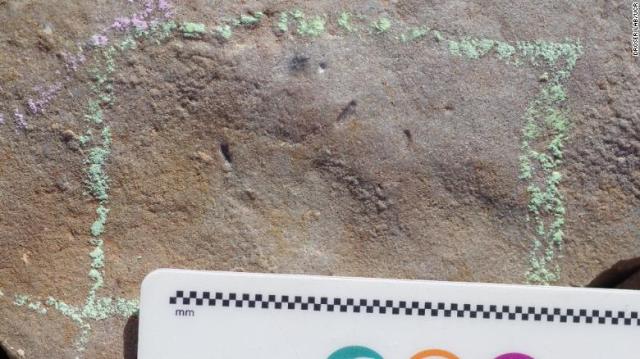

Burrows were found in stone that belonged to a tiny creature who lived billions of years ago.

Then, they turned to fossilized burrows, dated to the Ediacaran Period some 555 million years ago, found in Nilpena, South Australia. For 15 years, scientists knew they were created by bilaterians. But there was no evidence of what made the burrows and lived in them.

That is, until researchers decided to take a closer look at the burrows. Geology professor Mary Droser and doctoral graduate Scott Evans, both from the University of California, Riverside, spotted impressions shaped like ovals near the burrows.

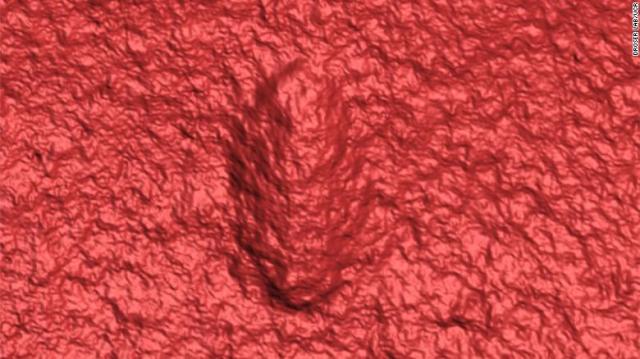

A 3-D laser scan revealed the impressions contained evidence of a body shaped and sized like a rice grain, with a noticeable head, tail and even V-shaped grooves suggesting muscles.

Contractions of the muscles would have enabled the creature to move and create the burrows, like the way a worm moves. Patterns of displaced sediment and signs of feeding led the researchers to determine that it had a mouth, gut and posterior opening.

And the size of the creature matched with the size of the burrows they found.

The study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We thought these animals should have existed during this interval, but always understood they would be difficult to recognize,” Evans said. “Once we had the 3D scans, we knew that we had made an important discovery.”

A 3D scan revealed the shape and characteristics of the creature that made the burrows.

The researchers involved in the study named the creature Ikaria wariootia. The first name translates to “meeting place” in the Adnyamathanha language. Adnyamathanha is the name of contemporary Indigenous Australian people that live in the area where the fossil was found. And the name of the species is a variation on a waterway in the area, called Warioota Creek.

The fossilized burrows were found beneath the impressions of other fossils in the lowest layer of Nilpena’s Ediacaran Period deposits. During its lifetime, Ikaria searched for the organic matter it fed on by burrowing through layers of sand on the ocean floor. Given that the burrows track through sand that was oxygenated, rather than toxic spots, suggest the creature had basic senses.

“Burrows of Ikaria occur lower than anything else. It’s the oldest fossil we get with this type of complexity,” Droser said. “We knew that we also had lots of little things and thought these might have been the early bilaterians that we were looking for.”

Droser also explained that other, larger fossils belonging to other creatures they found in the past were likely evolutionary dead-ends.

“This is what evolutionary biologists predicted,” Droser said. “It’s really exciting that what we have found lines up so neatly with their prediction.”

https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/23/world/animal-ancestor-ikaria-scn/index.html