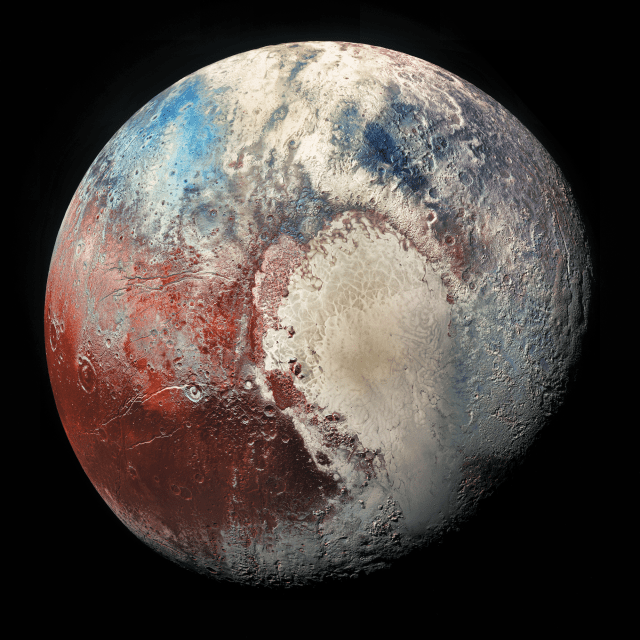

This view of Pluto’s Sputnik Planitia nitrogen-ice plain was captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft during its flyby of the dwarf planet in July 2015.

At its heart, Pluto may be a gigantic comet.

Researchers have come up with a new theory about the dwarf planet’s origins after taking a close look at Sputnik Planitia, the vast nitrogen-ice glacier that constitutes the left lobe of Pluto’s famous “heart” feature.

“We found an intriguing consistency between the estimated amount of nitrogen inside the glacier and the amount that would be expected if Pluto was formed by the agglomeration of roughly a billion comets or other Kuiper Belt objects similar in chemical composition to 67P, the comet explored by Rosetta,” Chris Glein, a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, said in a statement.

The European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission orbited Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from 2014 through 2016. The orbiting mothership also dropped a lander named Philae onto the icy body, pulling off the first-ever soft touchdown on a comet’s surface. (The Kuiper Belt is the ring of frigid objects beyond Neptune’s orbit; Pluto is the belt’s largest resident.)

Glein and his SwRI colleague Hunter Waite devised the new Pluto-formation scenario after analyzing data from Rosetta and NASA’s New Horizons mission, which flew by Pluto in July 2015.

The scientists also made some inferences about the dwarf planet’s evolution in their new study, which was published online Wednesday (May 23) in the journal Icarus.

“Our research suggests that Pluto’s initial chemical makeup, inherited from cometary building blocks, was chemically modified by liquid water, perhaps even in a subsurface ocean,” Glein said.

Glein and Waite aren’t claiming to have nailed down Pluto’s origin definitively; a “solar model,” in which the dwarf planet coalesced from cold ices with a chemical composition closer to that of the sun, also remains in play, the duo said.

“This research builds upon the fantastic successes of the New Horizons and Rosetta missions to expand our understanding of the origin and evolution of Pluto,” Glein said.

“Using chemistry as a detective’s tool, we are able to trace certain features we see on Pluto today to formation processes from long ago,” he added. “This leads to a new appreciation of the richness of Pluto’s ‘life story,’ which we are only starting to grasp.”

Rosetta’s mission ended in September 2016, when the probe’s handlers steered it to an intentional crash-landing on 67P’s surface. New Horizons’ work, however, is far from done. The NASA spacecraft is speeding toward a flyby of a small Kuiper Belt object known officially as 2014 MU69 (and unofficially as Ultima Thule). This close encounter, which will occur on Jan. 1, 2019, about 1 billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) beyond Pluto’s orbit, is the centerpiece of New Horizons’ extended mission.

https://www.space.com/40687-pluto-formation-1-billion-comets.html