by Debora MacKenzie

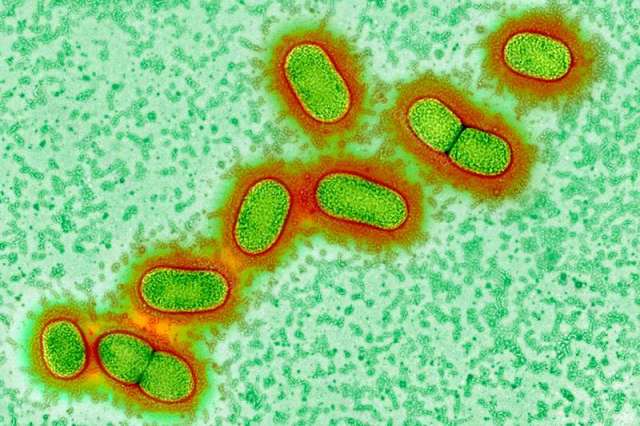

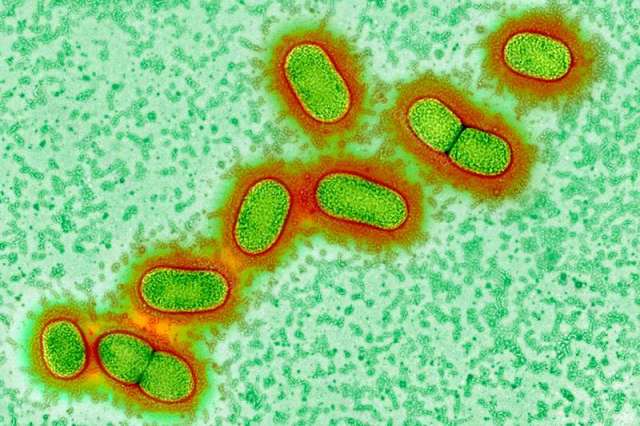

We may finally have found a long-elusive cause of Alzheimer’s disease: Porphyromonas gingivalis, the key bacteria in chronic gum disease. That’s bad, as gum disease affects around a third of all people. But the good news is that a drug that blocks the main toxins of P. gingivalis is entering major clinical trials this year, and research published this week shows it might stop and even reverse Alzheimer’s. There could even be a vaccine.

Alzheimer’s is one of the biggest mysteries in medicine. As populations have aged, dementia has skyrocketed to become the fifth biggest cause of death worldwide. Alzheimer’s constitutes some 70 per cent of these cases and yet, we don’t know what causes it. The disease often involves the accumulation of proteins called amyloid and tau in the brain, and the leading hypothesis has been that the disease arises from defective control of these two proteins. But research in recent years has revealed that people can have amyloid plaques without having dementia. So many efforts to treat Alzheimer’s by moderating these proteins have failed, and the hypothesis has now been seriously questioned.

Indeed, evidence has been growing that the function of amyloid proteins may be as a defence against bacteria, leading to a spate of recent studies looking at bacteria in Alzheimer’s, particularly those that cause gum disease, which is known to be a major risk factor for the condition.

Bacteria involved in gum disease and other illnesses have been found after death in the brains of people who had Alzheimer’s, but until now, it hasn’t been clear whether these bacteria caused the disease or simply got in via brain damage caused by the condition.

Gum disease link

Multiple research teams have been investigating P. gingivalis, and have so far found that it invades and inflames brain regions affected by Alzheimer’s; that gum infections can worsen symptoms in mice genetically engineered to have Alzheimer’s; and that it can cause Alzheimer’s-like brain inflammation, neural damage, and amyloid plaques in healthy mice.

“When science converges from multiple independent laboratories like this, it is very compelling,” says Casey Lynch of Cortexyme, a pharmaceutical firm in San Francisco, California.

In the new study, Cortexyme have now reported finding the toxic enzymes – called gingipains – that P. gingivalis uses to feed on human tissue in 96 per cent of the 54 Alzheimer’s brain samples they looked at, and found the bacteria themselves in all three Alzheimer’s brains whose DNA they examined.

“This is the first report showing P. gingivalis DNA in human brains, and the associated gingipains, co-lococalising with plaques,” says Sim Singhrao, of the University of Central Lancashire, UK. Her team previously found that P. gingivalis actively invades the brains of mice with gum infections. She adds that the new study is also the first to show that gingipains slice up tau protein in ways that could allow it to kill neurons, causing dementia.

The bacteria and its enzymes were found at higher levels in those who had experienced worse cognitive decline, and had more amyloid and tau accumulations. The team also found the bacteria in the spinal fluid of living people with Alzheimer’s, suggesting that this technique may provide a long-sought after method of diagnosing the disease.

When the team gave P. gingivalis gum disease to mice, it led to brain infection, amyloid production, tangles of tau protein, and neural damage in the regions and nerves normally affected by Alzheimer’s.

Cortexyme had previously developed molecules that block gingipains. Giving some of these to mice reduced their infections, halted amyloid production, lowered brain inflammation and even rescued damaged neurons.

The team found that an antibiotic that killed P. gingivalis did this too, but less effectively, and the bacteria rapidly developed resistance. They did not resist the gingipain blockers. “This provides hope of treating or preventing Alzheimer’s disease one day,” says Singhrao.

New treatment hope

Some brain samples from people without Alzheimer’s also had P. gingivalis and protein accumulations, but at lower levels. We already know that amyloid and tau can accumulate in the brain for 10 to 20 years before Alzheimer’s symptoms begin. This, say the researchers, shows P. gingivalis could be a cause of Alzheimer’s, but it is not a result.

Gum disease is far more common than Alzheimer’s. But “Alzheimer’s strikes people who accumulate gingipains and damage in the brain fast enough to develop symptoms during their lifetimes,” says Lynch. “We believe this is a universal hypothesis of pathogenesis.”

Cortexyme reported in October that the best of their gingipain blockers had passed initial safety tests in people, and entered the brain. It also seemed to improve participants with Alzheimer’s. Later this year the firm will launch a larger trial of the drug, looking for P. gingivalis in spinal fluid, and cognitive improvements, before and after.

They also plan to test it against gum disease itself. Efforts to fight that have led a team in Melbourne to develop a vaccine for P. gingivalis that started tests in 2018. A vaccine for gum disease would be welcome – but if it also stops Alzheimer’s the impact could be enormous.

Journal reference: Science Advances

https://www.newscientist.com/article/2191814-we-may-finally-know-what-causes-alzheimers-and-how-to-stop-it/