There are no instant, miracle cures. But recent studies suggest we have more control over our cognitive health than we might think. It just takes some effort.

When it comes to battling dementia, the unfortunate news is this: Medications have proven ineffective at curing or stopping the disease and its most common form, Alzheimer’s disease. But that isn’t the end of the story. According to a recent wave of scientific studies, we have more control over our cognitive health than is commonly known. We just have to take certain steps—ideally, early and often—to live a healthier lifestyle.

In fact, according to a recent report commissioned by the Lancet, a medical journal, around 35% of dementia cases might be prevented if people do things including exercising and engaging in cognitively stimulating activities. “When people ask me how to prevent dementia, they often want a simple answer, such as vitamins, dietary supplements or the latest hyped idea,” says Eric Larson, a physician at Kaiser Permanente in Seattle and one of a group of scientists who helped prepare the report. “I tell them they can take many common-sense actions that promote health throughout life.”

The Lancet report, distilling the findings of hundreds of studies, identifies several factors that likely contribute to dementia risk, many of which can be within people’s power to control. These include midlife obesity, physical inactivity, high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, social isolation and low education levels.

Of course, there are no guarantees. Dementia is a complicated disease that has multiple causes and risk factors, some of which remain unknown. Nevertheless, there is increasing evidence that people—even those who inherit genes that put them at greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s in later life—can improve their chances by adopting lifestyle changes.

“It’s not just about running three times a week,” says Sarah Lenz Lock, executive director of AARP’s Global Council on Brain Health. “Instead, it’s about a package of behaviors, including aerobic exercise, strength training, a healthy diet, sleep and cognitive training.”

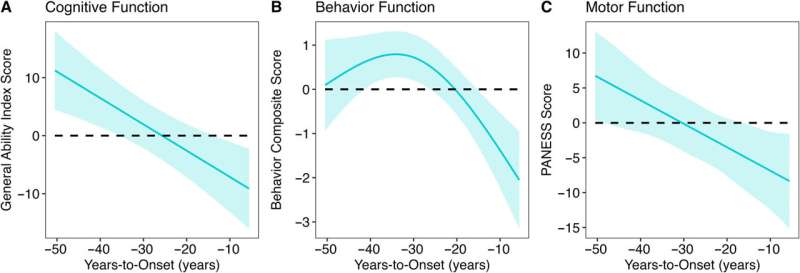

Because most neurodegenerative diseases take years, if not decades, to develop, researchers say the best time to focus on brain health is long before symptoms occur—ideally by midlife if not before. Still, they emphasize that it is never too late to start.

What follows is a look at what scientific studies tell us about possible ways to reduce dementia risk.

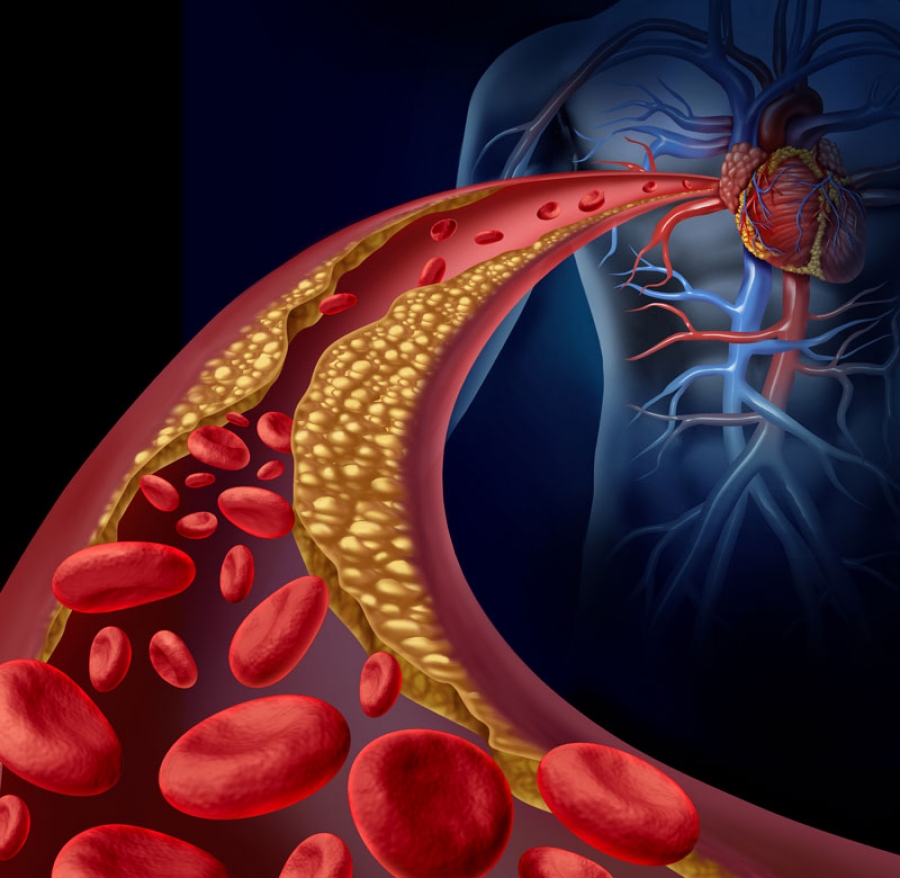

1. Blood-pressure control

The potential role that cardiovascular health—including blood pressure—plays in dementia has been one of the tantalizing highlights of recent research based on the Framingham Heart Study, which has followed thousands of residents of Framingham, Mass., and their relatives since 1948.

The research found a 44% decline in the dementia rate among people age 60 or older for the period 2004 to 2008, compared with 1977 to 1983. Diagnoses fell to two for every 100 study participants from 3.6 in the earlier period. Over the same roughly 30 years, the average age at which dementia was diagnosed rose to 85 from 80.

Co-author Claudia Satizabal, an assistant professor at UT Health San Antonio, says the research suggests that improvements in cardiovascular health and education levels help explain the trend. Improvements in dementia rates have occurred only in participants “who had at least a high-school diploma,” the study says. And as dementia rates have fallen, the study also says, so have the rates of “stroke and other cardiovascular diseases,” thanks in part to a greater use of blood-pressure medication.

Unlike studies in which participants are randomly assigned to different treatment groups and then monitored for results, the Framingham study and others that analyze population data cannot definitively prove a cause-and-effect relationship. Dr. Satizabal says that while the significant decline in dementia rates since 1977 suggests that management of stroke and heart issues could have contributed, that “is something that needs more research.”

A recent study that randomly assigned participants to different treatment goals offers further evidence for the idea that high blood pressure is a treatable risk factor that leads to dementia.

In 2010, researchers at Wake Forest School of Medicine began enrolling almost 9,400 people age 50 and older with high blood pressure in one of two groups. With the aid of medication, one group reduced its systolic blood pressure—which measures pressure in the arteries when the heart contracts—to less than 120. The other group aimed for less than 140.

The group with lower blood pressures experienced such significantly lower rates of death, strokes and heart attacks that in 2015 the researchers stopped the trial ahead of schedule. The scientists concluded it would be unethical to continue because most people should be targeting the lower blood pressure, says the study’s co-author Jeff Williamson, a Wake Forest medical school professor.

In 2017 and 2018, the researchers performed a final round of cognitive tests on participants and discovered that the lower-blood-pressure group had 19% fewer diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment, often a precursor to dementia, and 15% fewer cases of any type of dementia, mild or otherwise.

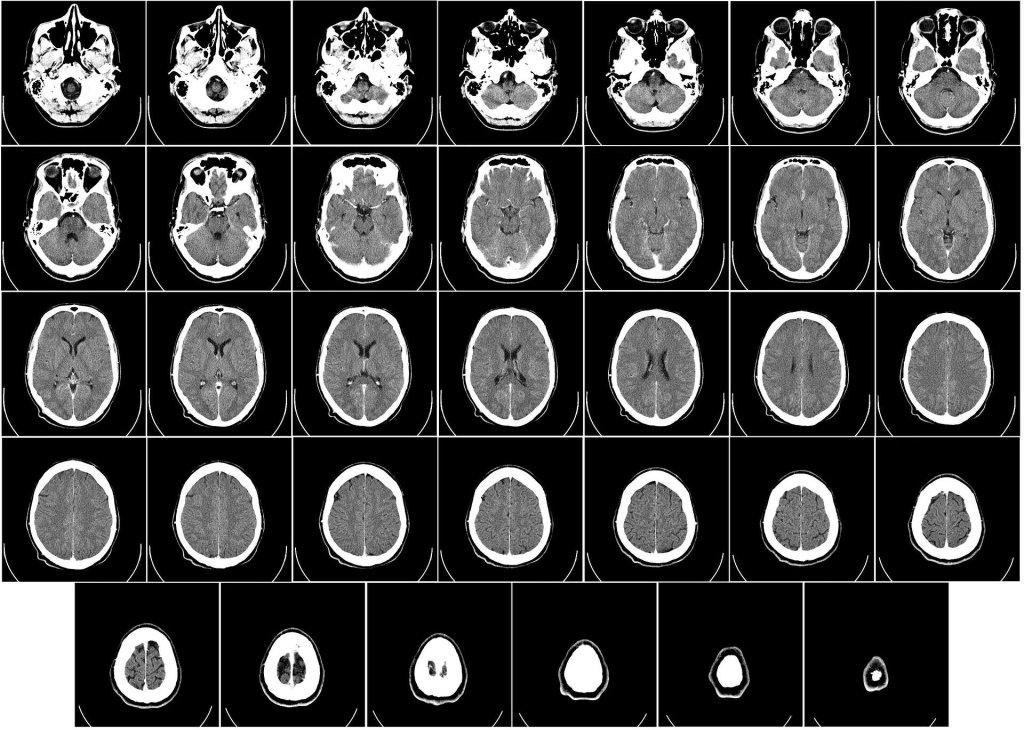

Using MRIs, the researchers scanned 673 participants’ brains and, upon follow-up, found less damaging changes in the lower-blood-pressure group.

“This is the first trial that has demonstrated an effective strategy for prevention of cognitive impairment,” says Kristine Yaffe, professor of psychiatry, neurology and epidemiology at the University of California, San Francisco. “That’s pretty big news,” says Dr. Yaffe, who wasn’t involved in the study.

2. Exercise

Several studies that have followed large numbers of people for years suggest that physically active individuals are less likely than inactive peers are to develop dementia, according to a recent World Health Organization report.

Exercise increases the flow of blood to the brain, improves the health of blood vessels and raises the level of HDL cholesterol, which together help protect against cardiovascular disease and dementia, says Laura Baker, a professor at Wake Forest School of Medicine. Exercise can also lead to the formation of new brain synapses and protect brain cells from dying.

Prof. Baker’s studies suggest that aerobic exercise can help improve cognitive function in people with mild memory, organizational and attention deficits, which are often the first symptoms of cognitive impairment.

One recent study conducted by Prof. Baker and several co-authors enrolled 65 sedentary adults ages 55 to 89 with mild memory problems. For six months, half completed four 60-minute aerobic-exercise sessions at the gym each week. Under a trainer’s supervision, they exercised mainly on treadmills at 70% to 80% of maximum heart rate. The other half did stretching exercises at 35% of maximum heart rate.

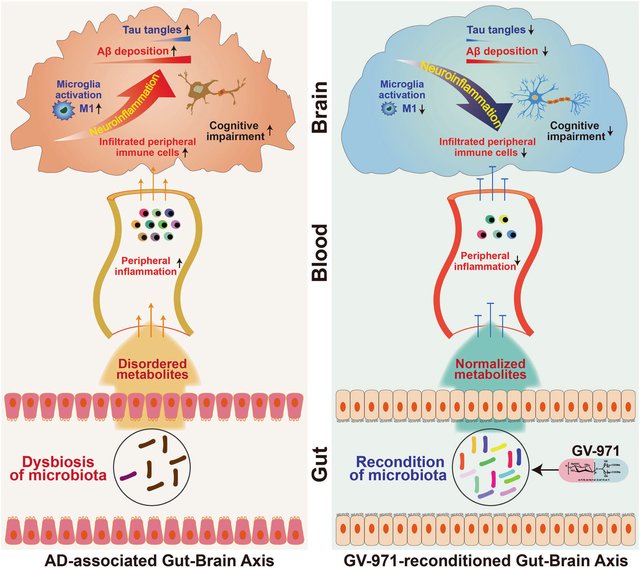

At the beginning and end of the study, researchers collected participants’ blood and spinal fluid and obtained MRI scans of their brains. Over the six months, the aerobic-exercise group had a statistically significant reduction in the level in their spinal fluid of tau protein, which accumulates in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. They also had increased blood flow to areas of the brain that are important for attention and concentration, and their scores on cognitive tests improved. The stretching group, in contrast, showed no improvement on cognitive tests or tau levels.

3. Cognitive training

Many population studies suggest that education increases cognitive reserve, a term for the brain’s ability to compensate for neurological damage. The Framingham study, for example, found that participants with at least a high-school diploma benefited the most from declining dementia rates, compared with participants with less education.

In another population study, researchers at Columbia University analyzed data from 593 people age 60 or older, 106 of whom developed dementia. People with clerical, unskilled or semiskilled jobs had greater risk of getting the disease than managers and professionals.

In a separate study, some of the same researchers followed 1,772 people age 65 or older, 207 of whom developed dementia. After adjusting the results for age, ethnic group, education and occupation, the authors found that people who engaged in more than six activities a month—including hobbies, reading, visiting friends, walking, volunteering and attending religious services—had a 38% lower rate of developing dementia than people who did fewer activities.

In yet another study, researchers at institutions including Rush University Medical Center’s Rush Institute for Healthy Aging examined the brains of 130 deceased people who had undergone cognitive evaluations when alive. Among individuals in whom similar levels of Alzheimer’s-related brain changes were seen in the postmortem examinations, the researchers found that those who had more education generally had shown higher cognitive function.

Yaakov Stern, a professor at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons who has written about these studies and the impact of education on dementia, recommends maintaining “educational and mentally stimulating activities throughout life.” This fosters growth of new neurons and may slow the rate at which certain regions of the brain shrink with age. It also promotes cognitive reserve, he says.

4. Diet

Efforts to study the impact of diet on dementia are relatively new, but there are some indications that certain diets may be beneficial in lowering the risk of dementia.

Several population studies, for instance, suggest that people with a Mediterranean diet, which is high in fish, fruits, nuts and vegetables, have lower rates of dementia, according to the World Health Organization.

But a variation on that diet may offer even more protection against the development of Alzheimer’s disease, according to a study released in 2015.

In this study, researchers including Dr. Martha Clare Morris, director of the Rush Institute for Healthy Aging, analyzed data from 923 people ages 58 to 98 who kept detailed food diaries about what they ate from 2004 to 2013.

In total, 158 subjects developed dementia. But among individuals who remained cognitively healthy, a high proportion had consumed a diet heavy in leafy green and other vegetables, nuts, berries, beans, whole grains, fish, poultry, olive oil and wine (in moderation). Their diets were limited in red meat, butter, cheese, sweets and fried and fast foods.

This diet, which researchers named the Mind diet, shares many elements of a Mediterranean diet. But the Mind diet prescribes more foods—including berries and leafy green vegetables—that are associated with lower rates of neurological diseases.

The researchers scored each of the 923 participants on how closely their detailed eating habits followed three diets: Mind, Mediterranean, and Dash diet, designed to reduce high blood pressure. For each diet, researchers ranked the participants based on their scores, subdividing them by the degree to which they followed each diet—closely, partly or little.

This led to several discoveries: First, there were about 50% fewer Alzheimer’s diagnoses among participants who most closely followed either the Mind diet or the Mediterranean diet, compared with those who followed either diet only a little. For the Dash diet, there was a 39% reduction for those who were most faithful to its rules.

Meanwhile, even those who only partly followed the Mind diet saw a 35% reduction in Alzheimer’s diagnoses, while no reduction was seen for those who only partly followed either the Mediterranean or Dash diet.

In contrast to the Mediterranean and Dash diets, “even modest adherence to the Mind diet may have substantial benefits for prevention of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Kristin Gustashaw, a dietitian at Rush.

5. Sleep

No one knows for sure why we sleep. One theory is that sleep helps us remember important information by performing a critical housekeeping function on brain synapses, including eliminating some connections and strengthening others.

Another theory is that sleep washes “toxic substances out of our brains that shouldn’t be there,” including beta amyloid and tau proteins that are implicated in Alzheimer’s, says Ruth Benca, a professor of medicine at the University of California, Irvine.

In a 2015 study, Prof. Benca and others examined 98 participants without dementia ages 50 to 73. Many were at genetic risk for the disease. Brain scans revealed that those reporting more sleep problems had higher levels of amyloid deposits in areas of the brain typically affected by Alzheimer’s.

“Poor sleep may be a risk factor for Alzheimer’s,” says Prof. Benca, who is conducting a study to see whether treating sleep problems may help prevent dementia.

She says sleep—or a lack of it—may help explain why about two-thirds of Alzheimer’s patients are women. Some researchers theorize that during menopause women can become vulnerable to the disease, in part due to increased prevalence of insomnia.

6. Combination

There is a growing consensus that when it comes to preserving brain health, the more healthy habits you adopt, the better.

According to a forthcoming study of 2,765 older adults by researchers at Rush, nonsmokers who stuck to the Mind diet, got regular exercise, engaged in cognitively stimulating activities and drank alcohol in moderation had 60% fewer cases of dementia over six years than people with just one such habit.

A study published in July found that people at greater genetic risk for Alzheimer’s appear to benefit just as much from eating well, exercising and drinking moderately as those who followed the same habits but weren’t at elevated genetic risk for the disease.

The study, by researchers including Kenneth Langa, associate director of the Institute of Gerontology at the University of Michigan, examined data from 196,383 Britons age 60 and older. Over about a decade, there were 38% fewer dementia diagnoses among individuals who had healthy habits and a gene, APOE4, that puts people at higher risk for Alzheimer’s, than there were among people who had the gene and poor habits. The gene increases the risk for Alzheimer’s by two to 12 times, depending on how many copies a person has.

Among participants with low genetic risk for Alzheimer’s, healthy habits were associated with a 40% reduction in the incidence of the disease. The results suggest a correlation between lifestyle, genetic risk and dementia, the study says.

Many point to a recent clinical trial in Finland of 1,260 adults ages 60 to 77 as proof that a multipronged approach can work.

The researchers, from institutions including the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and the National Institute for Health and Welfare in Helsinki, randomly assigned half of the participants, all deemed at high risk for dementia, to regular sessions with nutritionists, exercise trainers and instructors in computerized brain-training programs. The participants attended social events and were closely monitored for conditions including high blood pressure, excess abdominal weight and high blood sugar.

“They got support from each other to make lifestyle changes,” says co-author Miia Kivipelto, a professor at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden.

The other half received only general health advice.

After two years, both groups showed improvements in cognitive performance. But the overall scores of the intensive-treatment group improved by 25% more than the scores for the other group. The intensive-treatment group scored between 40% and 150% better on tests of executive function, mental speed and complex memory tasks, suggesting that a multifaceted approach can “improve or maintain cognitive functioning in at-risk elderly people,” the study says.

“We are studying whether exercise and lifestyle can be medicine to protect brain health as we get older,” says Prof. Baker, who is overseeing a U.S. study modeled on the Finnish trial.

https://apple.news/AzlC5CLNvQJWJrsP-qrJFIw