by Bahar Golipour

What is the earliest memory you have?

Most people can’t remember anything that happened to them or around them in their toddlerhood. The phenomenon, called childhood amnesia, has long puzzled scientists. Some have debated that we forget because the young brain hasn’t fully developed the ability to store memories. Others argue it is because the fast-growing brain is rewiring itself so much that it overwrites what it’s already registered.

New research that appears in Nature Neuroscience this week suggests that those memories are not forgotten. The study shows that when juvenile rats have an experience during this infantile amnesia period, the memory of that experience is not lost. Instead, it is stored as a “latent memory trace” for a long time. If something later reminds them of the original experience, the memory trace reemerges as a full blown, long-lasting memory.

Taking a (rather huge) leap from rats to humans, this could explain how early life experiences that you don’t remember still shape your personality; how growing up in a rich environment makes you a smarter person and how early trauma puts you at higher risk for mental health problems later on.

Scientists don’t know whether we can access those memories. But the new study shows childhood amnesia coincides with a critical time for the brain ― specifically the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped brain structure crucial for memory and learning. Childhood amnesia corresponds to the time that your brain matures and new experiences fuel the growth of the hippocampus.

In humans, this period occurs before pre-school, likely between the ages 2 and 4. During this time, a child’s brain needs adequate stimulation (mostly from healthy social interactions) so it can better develop the ability to learn.

And not getting enough healthy mental activation during this period may impede the development of a brain’s learning and memory centers in a way that it cannot be compensated later.

“What our findings tell us is that children’s brains need to get enough and healthy activation even before they enter pre-school,” said study leader Cristina Alberini, a professor at New York University’s Center for Neural Science. “Without this, the neurological system runs the risk of not properly developing learning and memory functions.”

The findings may illustrate one mechanism that could in part explain scientific research that shows poverty can shrink children’s brains.

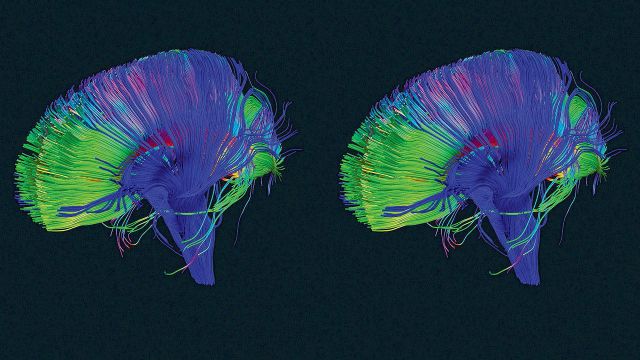

Extensive research spanning decades has shown that low socioeconomic status is linked to problems with cognitive abilities, higher risk for mental health issues and poorer performance in school. In recent years, psychologists and neuroscientists have found that the brain’s anatomy may look different in poor children. Poverty is also linked to smaller brain surface area and smaller volume of the white matter connecting brain areas, as well as smaller hippocampus. And a 2015 study found that the differences in brain development explain up to 20 percent of academic performance gap between children from high- and low-income families.

Critical Periods

For the brain, the first few years of life set the stage for the rest of life.

Even though the nervous system keeps some of its ability to rewire throughout life, several biochemical events that shape its core structure happen only at certain times. During these critical periods of the developmental stages, the brain is acutely sensitive to new sights, sounds, experiences and external stimulation.

Critical periods are best studied in the visual system. In the 1960s, scientists David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel showed that if they close one eye of a kitten from birth for just for a few months, its brain never learns to see properly. The neurons in the visual areas of the brain would lose their ability respond to the deprived eye. Adult cats treated the same way don’t show this effect, which demonstrates the importance of critical periods in brain development for proper functioning. This finding was part of the pioneering work that earned Hubel and Wiesel the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

In the new study in rats, the team shows that a similar critical period may be happening to the hippocampus.

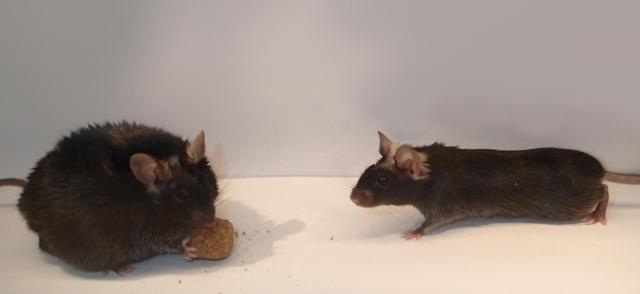

Alberini and her colleagues took a close look at what exactly happens in the brain of rats in their first 17 days of life (equivalent to the first three years of a human’s life). They created a memory for the rodents of a negative experience: every time the animals entered a specific corner of their cage, they received a mildly painful shock to their foot. Young rats, like kids, aren’t great at remembering things that happened to them during their infantile amnesia. So although they avoided that corner right after the shock, they returned to it only a day later. In contrast, a group of older rats retained the memory and avoided this place for a long time.

However, the younger rats, had actually kept a trace of the memory. A reminder (such as another foot shock in another corner) was enough to resurrect the memory and make the animals avoid the first corner of the cage.

Researchers found a cascade of biochemical events in the young rats’ brains that are typically seen in developmental critical periods.

“We were excited to see the same type of mechanism in the hippocampus,” Alberini told The Huffington Post.

The Learning Brain And Its Mysteries

Just like the kittens’ brain needed light from the eyes to learn to see, the hippocampus may need novel experiences to learn to form memories.

“Early in life, while the brain cannot efficiently form long-term memories, it is ‘learning’ how to do so, making it possible to establish the abilities to memorize long-term,” Alberini said. “However, the brain needs stimulation through learning so that it can get in the practice of memory formation―without these experiences, the ability of the neurological system to learn will be impaired.”

This does not mean that you should put your kids in pre-pre-school, Alberini told HuffPost. Rather, it highlights the importance of healthy social interaction, especially with parents, and growing up in an environment rich in stimulation. Most kids in developed countries are already benefiting from this, she said.

But what does this all mean for children who grow up exposed to low levels of environmental stimulation, something more likely in poor families? Does it explain why poverty is linked to smaller brains? Alberini thinks many other factors likely contribute to the link between poverty and brain. But it is possible, she said, that low stimulation during the development of the hippocampus, too, plays a part.

Psychologist Seth Pollak of University of Wisconsin at Madison who has found children raised in poverty show differences in hippocampal development agrees.

Pollak believes the findings of the new study represent “an extremely plausible link between early childhood adversity and later problems.”

“We must always be cautious about generalizing studies of rodents to understanding human children,” Pollas added. “But the nonhuman animal studies, such as this one, provide testable hypotheses about specific mechanisms underlying human behavior.”

Although the link between poverty and cognitive performance has been repeatedly seen in numerous studies, scientists don’t have a good handle on how exactly many related factors unfold inside the developing brain, said Elizabeth Sowell, a researcher from the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Studies like this one provide “a lot of food for thought,” she added.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2016/07/24/the-things-you-dont-remember-shape-who-you-are/