by Emily Mullin

When David Graham wakes up in the morning, the flat white box that’s Velcroed to the wall of his room in Robbie’s Place, an assisted living facility in Marlborough, Massachusetts, begins recording his every movement.

It knows when he gets out of bed, gets dressed, walks to his window, or goes to the bathroom. It can tell if he’s sleeping or has fallen. It does this by using low-power wireless signals to map his gait speed, sleep patterns, location, and even breathing pattern. All that information gets uploaded to the cloud, where machine-learning algorithms find patterns in the thousands of movements he makes every day.

The rectangular boxes are part of an experiment to help researchers track and understand the symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

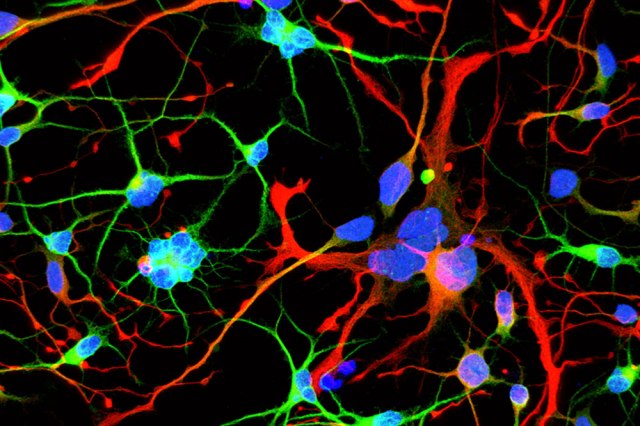

It’s not always obvious when patients are in the early stages of the disease. Alterations in the brain can cause subtle changes in behavior and sleep patterns years before people start experiencing confusion and memory loss. Researchers think artificial intelligence could recognize these changes early and identify patients at risk of developing the most severe forms of the disease.

Spotting the first indications of Alzheimer’s years before any obvious symptoms come on could help pinpoint people most likely to benefit from experimental drugs and allow family members to plan for eventual care. Devices equipped with such algorithms could be installed in people’s homes or in long-term care facilities to monitor those at risk. For patients who already have a diagnosis, such technology could help doctors make adjustments in their care.

Drug companies, too, are interested in using machine-learning algorithms, in their case to search through medical records for the patients most likely to benefit from experimental drugs. Once people are in a study, AI might be able to tell investigators whether the drug is addressing their symptoms.

Currently, there’s no easy way to diagnose Alzheimer’s. No single test exists, and brain scans alone can’t determine whether someone has the disease. Instead, physicians have to look at a variety of factors, including a patient’s medical history and observations reported by family members or health-care workers. So machine learning could pick up on patterns that otherwise would easily be missed.

David Graham, one of Vahia’s patients, has one of the AI-powered devices in his room at Robbie’s Place, an assisted living facility in Marlborough, Massachusetts.

Graham, unlike the four other patients with such devices in their rooms, hasn’t been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. But researchers are monitoring his movements and comparing them with patterns seen in patients who doctors suspect have the disease.

Dina Katabi and her team at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory initially developed the device as a fall detector for older people. But they soon realized it had far more uses. If it could pick up on a fall, they thought, it must also be able to recognize other movements, like pacing and wandering, which can be signs of Alzheimer’s.

Katabi says their intention was to monitor people without needing them to put on a wearable tracking device every day. “This is completely passive. A patient doesn’t need to put sensors on their body or do anything specific, and it’s far less intrusive than a video camera,” she says.

How it works

Graham hardly notices the white box hanging in his sunlit, tidy room. He’s most aware of it on days when Ipsit Vahia makes his rounds and tells him about the data it’s collecting. Vahia is a geriatric psychiatrist at McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and he and the technology’s inventors at MIT are running a small pilot study of the device.

Graham looks forward to these visits. During a recent one, he was surprised when Vahia told him he was waking up at night. The device was able to detect it, though Graham didn’t know he was doing it.

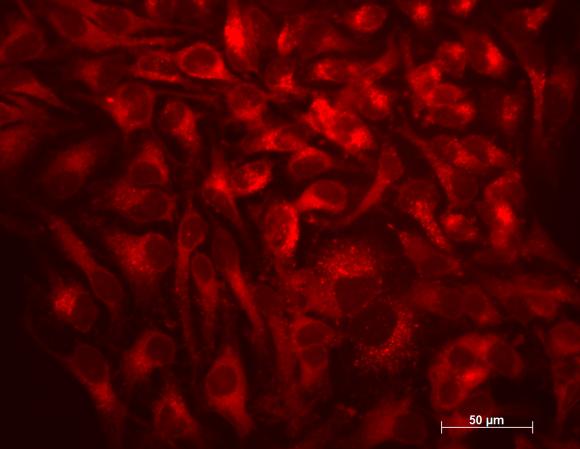

The device’s wireless radio signal, only a thousandth as powerful as wi-fi, reflects off everything in a 30-foot radius, including human bodies. Every movement—even the slightest ones, like breathing—causes a change in the reflected signal.

Katabi and her team developed machine-learning algorithms that analyze all these minute reflections. They trained the system to recognize simple motions like walking and falling, and more complex movements like those associated with sleep disturbances. “As you teach it more and more, the machine learns, and the next time it sees a pattern, even if it’s too complex for a human to abstract that pattern, the machine recognizes that pattern,” Katabi says.

Over time, the device creates large readouts of data that show patterns of behavior. The AI is designed to pick out deviations from those patterns that might signify things like agitation, depression, and sleep disturbances. It could also pick up whether a person is repeating certain behaviors during the day. These are all classic symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

“If you can catch these deviations early, you will be able to anticipate them and help manage them,” Vahia says.

In a patient with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Vahia and Katabi were able to tell that she was waking up at 2 a.m. and wandering around her room. They also noticed that she would pace more after certain family members visited. After confirming that behavior with a nurse, Vahia adjusted the patient’s dose of a drug used to prevent agitation.

Ipsit Vahia and Dina Katabi are testing an AI-powered device that Katabi’s lab built to monitor the behaviors of people with Alzheimer’s as well as those at risk of developing the disease.

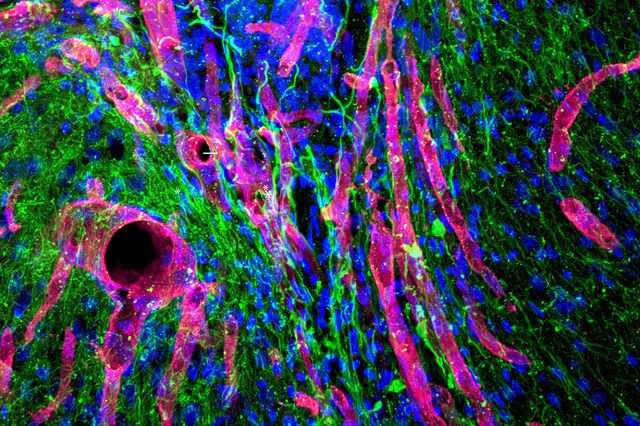

Brain changes

AI is also finding use in helping physicians detect early signs of Alzheimer’s in the brain and understand how those physical changes unfold in different people. “When a radiologist reads a scan, it’s impossible to tell whether a person will progress to Alzheimer’s disease,” says Pedro Rosa-Neto, a neurologist at McGill University in Montreal.

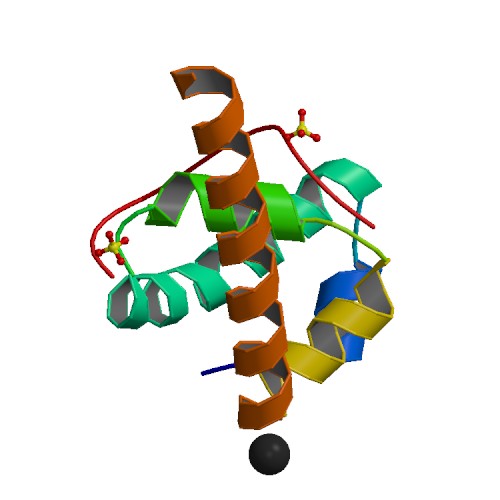

Rosa-Neto and his colleague Sulantha Mathotaarachchi developed an algorithm that analyzed hundreds of positron-emission tomography (PET) scans from people who had been deemed at risk of developing Alzheimer’s. From medical records, the researchers knew which of these patients had gone on to develop the disease within two years of a scan, but they wanted to see if the AI system could identify them just by picking up patterns in the images.

Sure enough, the algorithm was able to spot patterns in clumps of amyloid—a protein often associated with the disease—in certain regions of the brain. Even trained radiologists would have had trouble noticing these issues on a brain scan. From the patterns, it was able to detect with 84 percent accuracy which patients ended up with Alzheimer’s.

Machine learning is also helping doctors predict the severity of the disease in different patients. Duke University physician and scientist P. Murali Doraiswamy is using machine learning to figure out what stage of the disease patients are in and whether their condition is likely to worsen.

“We’ve been seeing Alzheimer’s as a one-size-fits all problem,” says Doraiswamy. But people with Alzheimer’s don’t all experience the same symptoms, and some might get worse faster than others. Doctors have no idea which patients will remain stable for a while or which will quickly get sicker. “So we thought maybe the best way to solve this problem was to let a machine do it,” he says.

He worked with Dragan Gamberger, an artificial-intelligence expert at the Rudjer Boskovic Institute in Croatia, to develop a machine-learning algorithm that sorted through brain scans and medical records from 562 patients who had mild cognitive impairment at the beginning of a five-year period.

Two distinct groups emerged: those whose cognition declined significantly and those whose symptoms changed little or not at all over the five years. The system was able to pick up changes in the loss of brain tissue over time.

A third group was somewhere in the middle, between mild cognitive impairment and advanced Alzheimer’s. “We don’t know why these clusters exist yet,” Doraiswamy says.

Clinical trials

From 2002 to 2012, 99 percent of investigational Alzheimer’s drugs failed in clinical trials. One reason is that no one knows exactly what causes the disease. But another reason is that it is difficult to identify the patients most likely to benefit from specific drugs.

AI systems could help design better trials. “Once we have those people together with common genes, characteristics, and imaging scans, that’s going to make it much easier to test drugs,” says Marilyn Miller, who directs AI research in Alzheimer’s at the National Institute on Aging, part of the US National Institutes of Health.

Then, once patients are enrolled in a study, researchers could continuously monitor them to see if they’re benefiting from the medication.

“One of the biggest challenges in Alzheimer’s drug development is we haven’t had a good way of parsing out the right population to test the drug on,” says Vaibhav Narayan, a researcher on Johnson & Johnson’s neuroscience team.

He says machine-learning algorithms will greatly speed the process of recruiting patients for drug studies. And if AI can pick out which patients are most likely to get worse more quickly, it will be easier for investigators to tell if a drug is having any benefit.

That way, if doctors like Vahia notice signs of Alzheimer’s in a person like Graham, they can quickly get him signed up for a clinical trial in hopes of curbing the devastating effects that would otherwise come years later.

Miller thinks AI could be used to diagnose and predict Alzheimer’s in patients in as soon as five years from now. But she says it’ll require a lot of data to make sure the algorithms are accurate and reliable. Graham, for one, is doing his part to help out.

https://www.technologyreview.com/s/609236/ai-can-spot-signs-of-alzheimers-before-your-family-does/