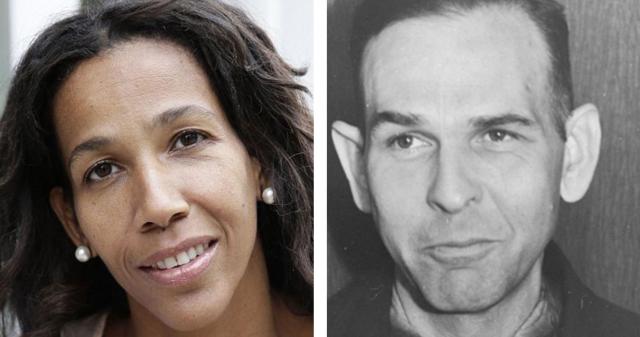

As a teenager during World War II, Freddie Oversteegen was one of only a few Dutch women to take up arms against the country’s Nazi occupiers. (Courtesy of National Hannie Schaft Foundation)

A recent image of Ms. Oversteegen. (Courtesy of National Hannie Schaft Foundation)

By Harrison Smith

She was 14 when she joined the Dutch resistance, though with her long, dark hair in braids she looked at least two years younger.

When she rode her bicycle down the streets of Haarlem in North Holland, firearms hidden in a basket, Nazi officials rarely stopped to question her. When she walked through the woods, serving as a lookout or seductively leading her SS target to a secluded place, there was little indication that she carried a handgun and was preparing an execution.

The Dutch resistance was widely believed to be a man’s effort in a man’s war. If women were involved, the thinking went, they were likely doing little more than handing out anti-German pamphlets or newspapers.

Yet Freddie Oversteegen and her sister Truus, two years her senior, were rare exceptions — a pair of teenage women who took up arms against Nazi occupiers and Dutch “traitors” on the outskirts of Amsterdam. With Hannie Schaft, a onetime law student with fiery red hair, they sabotaged bridges and rail lines with dynamite, shot Nazis while riding their bikes, and donned disguises to smuggle Jewish children across the country and sometimes out of concentration camps.

In perhaps their most daring act, they seduced their targets in taverns or bars, asked if they wanted to “go for a stroll” in the forest — and “liquidated” them, as Ms. Oversteegen put it, with a pull of the trigger.

“We had to do it,” she told one interviewer. “It was a necessary evil, killing those who betrayed the good people.” When asked how many people she had killed or helped kill, she demurred: “One should not ask a soldier any of that.”

Freddie Oversteegen, the last remaining member of the Netherlands’ most famous female resistance cell, died Sept. 5, one day before her 93rd birthday. She was living in a nursing home in Driehuis, five miles from Haarlem, and had suffered several heart attacks in recent years, said Jeroen Pliester, chairman of the National Hannie Schaft Foundation.

The organization was founded by Ms. Oversteegen’s sister in 1996 to promote the legacy of Schaft, who was captured and executed by the Nazis weeks before the end of World War II. “Schaft became the national icon of female resistance,” Pliester said, a martyr whose story was taught to schoolchildren across the Netherlands and memorialized in a 1981 movie, “The Girl With the Red Hair,” which took its title from her nickname.

Ms. Oversteegen served as a board member in her sister’s organization. But she “decided to be a little bit out of the limelight,” Pliester said, and was sometimes overshadowed by Schaft and Truus, the group’s leader.

“I have always been a little jealous of her because she got so much attention after the war,” Ms. Oversteegen told Vice Netherlands in 2016, referring to her sister. “But then I’d just think, ‘I was in the resistance as well.’ ”

It was, she said, a source of pride and of pain — a five-year experience that she never regretted, but that came to haunt her in peacetime. Late at night, unable to fall asleep, she sometimes recalled the words of an old battle song that served as an anthem for her and her sister: “We have carried the best to their graves/ torn and fired at, beaten till the blood ran/ surrounded by the executioners on the scaffold and jail/ but the raging of the enemy doesn’t frighten us.”

Freddie Nanda Oversteegen was born in the village of Schoten, now part of Haarlem, on Sept. 6, 1925. Her parents divorced when she was a child, and Freddie and Truus were raised primarily by their mother, a communist who instilled a sense of social responsibility in the young girls; she eventually remarried and had a son.

In interviews with anthropologist Ellis Jonker, collected in the 2014 book “Under Fire: Women and World War II,” Freddie Oversteegen recalled that their mother encouraged them to make dolls for children suffering in the Spanish Civil War, and beginning in the early 1930s volunteered with International Red Aid, a kind of communist Red Cross for political prisoners around the world.

Although living in poverty, sleeping on makeshift mattresses stuffed with straw, the family harbored refugees from Germany and Amsterdam, including a Jewish couple and a mother and son who lived in their attic. After German forces invaded the Netherlands in May 1940, the couples were moved to another location; Jewish community leaders feared a potential raid, because of the family’s well-known political leanings.

“They were all deported and murdered,” Ms. Oversteegen told Jonker. “We never heard from them again. It still moves me dreadfully, whenever I talk about it.”

Ms. Oversteegen and her sister began their resistance careers by distributing pamphlets (“The Netherlands have to be free!”) and hanging anti-Nazi posters (“For every Dutch man working in Germany, a German man will go to the front!”). Their efforts apparently attracted the attention of Frans van der Wiel, commander of the underground Haarlem Council of Resistance, who invited them to join his team — with their mother’s permission.

“Only later did he tell us what we’d actually have to do: sabotage bridges and railway lines,” Truus Oversteegen said, according to Jonker. “We told him we’d like to do that. ‘And learn to shoot, to shoot Nazis,’ he added. I remember my sister saying, ‘Well, that’s something I’ve never done before!’ ”

By Truus’s account, it was Freddie Oversteegen who became the first to shoot and kill someone. “It was tragic and very difficult and we cried about it afterwards,” Truus said. “We did not feel it suited us — it never suits anybody, unless they are real criminals. . . . One loses everything. It poisons the beautiful things in life.”

The Oversteegen sisters were officially part of a seven-person resistance cell, which grew to include an eighth member, Schaft, after she joined in 1943. But the three girls worked primarily as a stand-alone unit, Pliester said, acting on instructions from the Council of Resistance.

After the war ended in 1945, Truus worked as an artist, making paintings and sculptures inspired by her years with the resistance, and wrote a popular memoir, “Not Then, Not Now, Not Ever.” She died in 2016, two years after Prime Minister Mark Rutte awarded the sisters the Mobilization War Cross, a military honor for service in World War II.

For her part, Freddie Oversteegen told Vice that she coped with the traumas of the war “by getting married and having babies.” She married Jan Dekker, taking the name Freddie Dekker-Oversteegen, and raised three children. They survive her, as do her half brother and four grandchildren. Her husband, who worked at the steel company Hoogovens, is deceased.

In interviews, Ms. Oversteegen often spoke of the physics of killing — not the feel of the trigger or kick of the gun, but the inevitable collapse that followed, her victims’ fall to the ground.

“Yes,” she told one interviewer, according to the Dutch newspaper IJmuider Courant , “I’ve shot a gun myself and I’ve seen them fall. And what is inside us at such a moment? You want to help them get up.”