For the first time, scientists have detected microscopic microplastics lodged in the human brain. Researchers in Germany and Brazil say that 8 out of 15 autopsied adults had microplastics detected within their brain’s smell centers, the olfactory bulb.

The particles were likely breathed in over a lifetime, since tiny floating microplastics are ubiquitous in the air.

Although microplastics have already been found in human lungs, intestines, liver, blood, testicles and even semen, it had long been thought that the body’s protective blood-brain barrier might keep the particles out of the brain.

However, the new study suggests that there’s “a potential pathway for the translocation of microplastics to the brain” via the olfactory bulb, according to a team led by Luis Fernando Amato-Lourenco, of the Free University Berlin and Thais Mauad, an associate professor of pathology at the University of Sao Paolo in Brazil.

The team published its findings Sept. 16 in the journal JAMA Network Open.

“With much smaller nanoplastics entering the body with greater ease, the total level of plastic particles may be much higher,” Mauad said in a news release from the Plastic Health Council, a group that advocates for reductions in plastics use.

“What is worrying is the capacity of such particles to be internalized by cells and alter how our bodies function,” Mauad added.

The new study involved brain tissues from 15 routine autopsies conducted on deceased residents of Sao Paulo, Brazil. The individuals ranged in age at death from 33 to 100 (average age 69.5 years).

“A total of 16 synthetic polymer [plastic] particles and fibers were identified” in the brain olfactory bulbs of 8 of the 15 deceased people, the researchers report.

In nearly 44% of cases, the plastic was polypropylene—one of the most common plastics and used in everything from packaging to clothing and home accessories.

That suggests “indoor environments as a major source of inhaled microplastics,” the team said.

So just how are these microscopic fragments invading the brain?

Amato-Lourenco and colleagues point out that nasal mucosa lying outside the brain may interact with cerebrospinal fluid to allow entry of microplastics into the olfactory bulb via tiny “perforations” in bony structures found in this area.

“So when you breathe through your nose, your olfactory nerve directly samples particles and reacts to the particles that you are inhaling as a direct sensory mechanism,” said Dr. Wells Brambl, core faculty for medical toxicology at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New York City.

“The fact that there’s no blood-brain barrier there leads to direct access to the brain, and most importantly, right above the olfactory nerve are the frontal and prefrontal lobes, which are where we believe the seat of consciousness is,” added Brambl, who was not involved in the study.

Other studies have already shown that “environmental black carbon particles” from air pollution can be found in the olfactory bulb, and in rare cases, tiny amoebae that can trigger a deadly form of encephalitis are also detected there, the Brazilian researchers noted.

They said the new data “extend the notion that not only black carbon but also microplastics accumulate in the olfactory bulb in humans.”

Can these microplastics affect brain health? That’s not yet clear, Amato-Lourenco’s team said, but the “potential” is there.

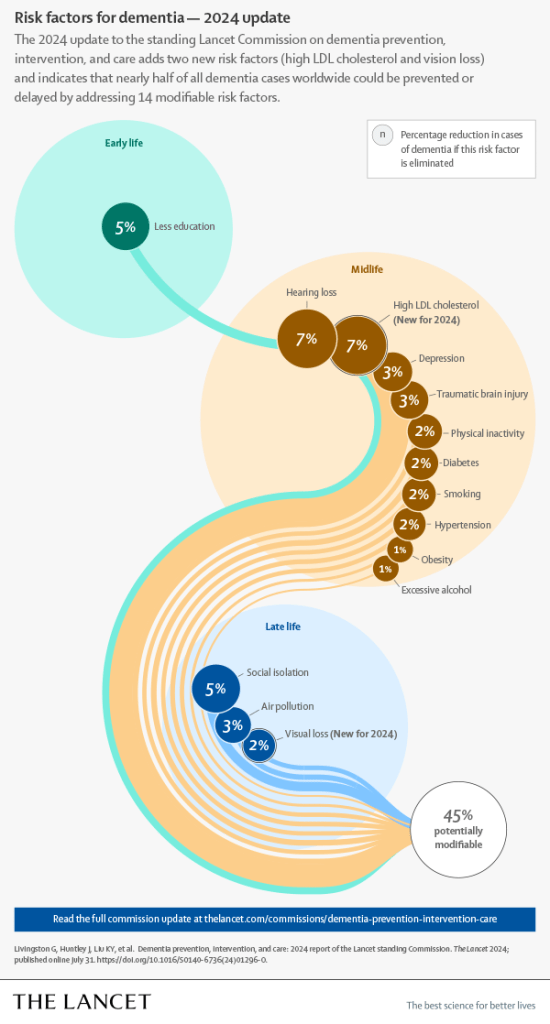

“Considering the potential neurotoxic effects caused by microplastics in the brain, and the widespread environmental contamination with plastics, our results should raise concern in the context of increasing prevalence of neuodegenerative diseases” such as Parkinson’s, ALS and other maladies, the researchers said.

“My intuition would say that it’s not good to have plastic in your brain,” Brambl said. “However, the data in long-term prospective studies have not yet been performed. So, it’s impossible to make any definitive conclusions.”

Still, he said, “I think that this study is very thought-provoking in the sense that we need to start thinking about this as a real public health concern for the long term.”

More information: Luís Fernando Amato-Lourenço et al, Microplastics in the Olfactory Bulb of the Human Brain, JAMA Network Open (2024). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.40018

Find out more about microplastics at Yale University.

Journal information: JAMA Network Open

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-09-microplastics-human-brain.html