Diabetes is so common in Patricia Graham’s neighbourhood that it has its own slang term. “At churches you run into people you ain’t seen in years, and they say, ‘I’ve got sugar,’” she says.

Graham does not quite have “sugar”, but when foot surgery in 2014 reduced her activity level, her blood sugar level soared. And there is a history of diabetes in her family: three of four brothers and her mother, who lost a leg to it.

So three times a week she comes to the smart, modern Diabetes Awareness and Wellness Network (Dawn) centre in Houston’s third ward, a historically African American district near downtown. Used by about 520 people a month, Dawn is in effect a free, city-run gym and support group for diabetics and pre-diabetics: a one-stop shop for inspiration, information and perspiration. Last Friday Graham, 68, was there for a walking session.

Not that she or the half-dozen other participants went anywhere. This was walking on the spot to pulsating music. Had the class stepped outside they would have enjoyed perfect conditions for a stroll: a blue sky and a temperature of 21C. If they had worked up an appetite, a soul food restaurant was only a 15-minute walk away, serving celebrated (if not exactly sugar-free) food that belies its unpromising location in a standard shopping mall on a busy road next to a dialysis centre.

But most of Houston is not built for walking, even on a sunny January day. There’s the constant traffic belching fumes that linger in the humid air; the uneven sidewalks that have a pesky habit of vanishing halfway along the street; the sheer distances to cover in this elongated, ever-expanding metropolis. Walking can feel like a transgressive act against Houston’s car-centric culture of convenience – and its status as the capital of the north American oil and gas industry.

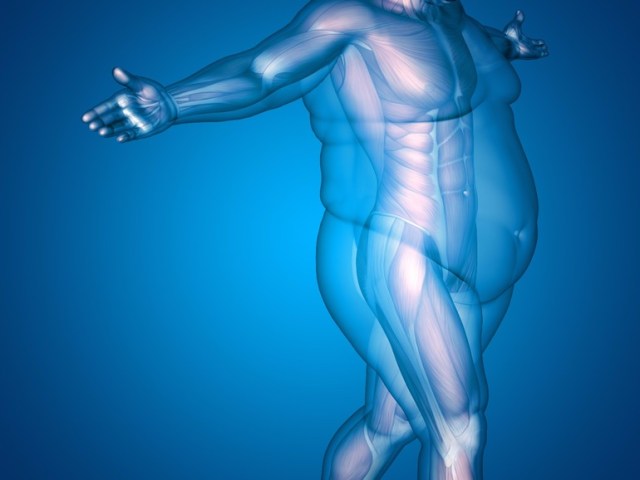

It’s one reason why Houston regularly finishes top, or close, in surveys that crown “America’s fattest city”. Unsurprisingly, it has a diabetes problem as outsized as its residents’ waistlines. By 2040, one in five Houstonians is predicted to have the disease.

According to data from pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the city is 9.1% – with an estimated one in four of these being undiagnosed. Almost a third of adult Houstonians self-describe as obese, according to a 2010-11 survey. Without action, the number of people with diabetes is projected to nearly treble by 2040 to 1.1 million people, with diabetes-related costs soaring from $4.1bn in 2015 to $11.4bn by 2040.

Graham is alarmed by the damage diabetes is wreaking on her community. “I was talking to my friends and saying, so many of the people we grew up with got diabetes and lost limbs,” she says. “It’s not even so much the seniors any more, it’s the young people. But it doesn’t scare them. They act like they’re not afraid.”

Another Dawn member, Verne Jenkins, was diagnosed three years ago. “I had picked up a bit of weight that I shouldn’t have,” says the 63-year-old. “I knew what to eat, I knew what I was doing, I just got out of control.”

Jenkins loves to bake but has cut back on carbs, red meat, salt and sugar, abstaining from one of her guilty pleasures, German chocolate cake. Not that it’s easy in a city with so much choice: “All these wonderful restaurants, all these different kinds of cuisines, of course you’re going to try some. I imagine it leads to our delinquency,” she says.

Graham has watched her diet since she was in her 20s. “I eat pretty good,” she said. “‘She eats like white folks’ – that’s what they tell me!”

Time poverty

Diabetes is a major cause of death, blindness, kidney disease and amputations in the US. While federal researchers announced last year that the rate of new diabetes cases dropped from 1.7 million in 2009 to 1.4 million in 2014, in Texas the percentage of diagnosed adults rose from 9.8% in 2009 to 11% in 2014.

Houston, America’s fourth-largest city, is one of five participating in the Cities Changing Diabetes programme, along with Mexico City, Copenhagen, Tianjin and Shanghai. Vancouver and Johannesburg are soon to join the project, which attempts to understand, publicise and combat the threat through cultural analysis.

“The majority of people with diabetes live in cities,” says Jakob Riis, an executive vice-president at Novo Nordisk, one of the lead partners in the programme alongside the Steno Diabetes Center and University College London. “We need to rethink cities so that they are healthier to live in … otherwise we’re not really addressing the root cause of the problem.”

One of the programme’s key – and perhaps surprising – findings, however, is that assessing the risk of developing diabetes is not as simple as dividing the population according to income and race. The problem is broad – much like Houston itself.

The view stretches for miles from Faith Foreman’s eighth-floor office next to the Astrodome, the famous old indoor baseball stadium. It’s an impressive sight, but for someone tasked with tackling the city’s diabetes epidemic, also a worrying one: the sheer scale of the urban sprawl is part of the problem. The threat of the disease has expanded along with the city.

A low cost of living and a strong jobs market helped Houston become one of the fastest growing urban areas in the US. In response, the city loosened its beltways. Its third major ring road is under construction, with a northwestern segment set to open soon that is some 35 miles from downtown.

Once completed, the Grand Parkway – whose northwestern segment has just opened – will boast a circumference of about 180 miles. That is far in excess of the 117 miles of the M25, although about 14 million people live inside the boundary of London’s orbital motorway, more than twice as many as reside in the Houston area.

Large homes sprout in the shadow of recently opened sections, promising cheap middle-class living with a heavy cost: a commute to central Houston of up to 90 minutes each way during rush hour, with minimal public transport options.

“A lot of time in Houston is spent in a car,” says Foreman, assistant director of Houston’s Department of Health and Human Services. This informs one of the Cities Changing Diabetes study’s most notable findings: that “time poverty” is among the risk factors in Houston for developing type 2 diabetes.

This means that young, relatively well-off people can also be considered a vulnerable population segment, even though they might not fit the traditional profile of people who may develop type 2 diabetes – that is, aged over 45, with high blood pressure and a high BMI, and perhaps disadvantaged through poverty or a lack of health insurance.

“You generally think of marginalised, lower income communities in poverty as your keys to health disparities but I think what we learned from our data in Houston is that we now have to expand the definition of what vulnerable is and what at-risk means. Just because we live in an urban environment, we may all indeed be vulnerable,” says Foreman.

In other words, not only its residents’ dietary choices but the way Houston is constructed as a city appears to be contributing to its diabetes problem, so tackling the issue requires architects as well as doctors; more sidewalks as well as fewer steaks.

Urban isolation is a key challenge, says David Napier of UCL, the lead academic for Cities Changing Diabetes. “Houston is growing so quickly and also expanding geographically at such a rapid rate. When you look at how difficult it is for people just to get out and walk, or walk to work; the fact that so many people commute long distances, spend a lot of time eating out – they have a number of obstacles to overcome,” he says.

A city with notoriously lax planning regulations is now making a conscious effort to put more care into its built environment, with more public transport, expanded bike trails, better parks and denser, more walkable neighbourhoods all evident in recent years, even as the suburbs continue to swell.

Foreman’s agency has more input when officials gather to map out the future city. “That is something that has been a big change over the last two or three years in Houston,” she says. “We are at the table and we are working with city planning to make those decisions.”

But prevention is a vital focus as well as treatment. Along with his team, Stephen Linder of the University of Texas’ school of public health – the local academic lead for Houston’s Cities Changing Diabetes research – gathered data on 5,000 households in Harris County, which includes much of the Houston area.

“One way to approach this project wasn’t to focus on diabetes itself but rather to look at some of the preconditioned social factors that seemed to generate the patterns of living that then led to the clinical signs that would designate people as being prediabetic,” he says from his office at the Texas Medical Center near downtown Houston – the world’s largest medical complex.

“These were people who had neither disadvantage nor biological risk factors. They tended to be the youngest group and would normally escape any kind of assessment – we called them the ‘time-pressured-young’. They’re the ones who did the long commutes; they’re the ones whose perception was they could not manage their day’s worth of stuff, that they have no time for anything.”

For this group, obesity is so prevalent in Houston that it distorts an understanding of what a healthy weight is, Linder found. “Their perception of their health was affected by their peers as opposed to other sorts of references. If all of their peers were overweight then in a relative sense they were fine. The judgments were about one’s peers and not relative to any sort of expert standard,” he says.

Three neighbourhoods were identified as having the highest concentration of people vulnerable to developing diabetes, and a Dallas-area research company, 2M, conducted detailed interviews with 125 residents. One place was particularly surprising: Atascocita, a desirable middle-class area near a large lake and golf courses, about 30 miles north of downtown.

Houston has become, according to a 2012 Rice University study, the most ethnically diverse large metropolitan area in the US. But this cosmopolitan air – one of the qualities sought by any place seeking to become a globally renowned city – may also unwittingly be contributing to the diabetes crisis, the study found.

Some in Atascocita, Linder said, “emphasised this sense of change and transition in their neighbourhoods, that that was a source of stress for them and that they were resistant to making changes in their own lives given the flux that was around them. Because that group happened to be older, even though they were economically secure they did have some other chronic diseases and they satisfied our biorisk characteristics.

“We call them concerned seniors. They weren’t making changes because there was too much else going on for them. And so if we were to say to them ‘you’ve got to change your diet’, they’d say ‘no, I can’t handle any more changes’.”

This matters since food portions are no exception to the “everything’s bigger in Texas” cliche, while Houston’s location near Mexico and the deep south, its embrace of the Lone Star state’s love of barbecued red meat and its enormous variety of restaurants serving international cuisine combine to unhealthy effect.

“The food that had a traditional aspect to it tended not to be the healthiest food – southern food that’s fried and lots of butter and lots of starch, then there’s African American soul food and then there’s Hispanic heavy fat, prepared tamales and the like, and so we found people kind of gravitated to what the UCL people called nourishing traditions,” Linder said.

“People used food as not only a reinforcement of tradition and ritual but also as a way of connecting socially. You’ve moved here from somewhere else, it’s a way to reinforce your identity, it’s a real cultural asset to have, but in a biological sense it’s not the best thing.”

For Linder, one lesson is that generalised advice about healthy eating that has long been part of diabetes awareness efforts may not be effective locally, given the complexity and variety of Houston’s neighbourhoods and the social factors that make populations vulnerable to diabetes.

“It does make the task of dietary change a much more complex one than the simple messages about changing your diet, eat more fruit and vegetables, get more colour on your plate would suggest. Those things bounce off, it’s not a useful set of interventions then for that particular group who rely on these nourishing traditions and find some solace in the change around them,” he said.

Foreman agrees that a targeted approach is vital. “How do you change diabetes in Houston? One neighbourhood at a time, in a sense, but at the same time you have bigger things that you can change systemwide in policies and how you work together collaboratively,” she said. “But then as you narrow it and get more granular it is neighbourhood, and what works in one neighbourhood may or may not work in another.”

Patricia Graham is hoping that the Dawn programme expands to other parts of the city to combat the dangerous union of unhealthy traditional food with a modern convenience culture. “Everything is food, and I mean lots of it and all the time,” she said. “Some people don’t know how to cook without grease or butter. That’s just the way we learn.”

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/feb/11/houston-health-crisis-diabetes-sugar-cars-diabetic?CMP=oth_b-aplnews_d-1

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the It’s Interesting community.