A UNSW-led team researching a drug to avoid insulin resistance was greeted with an unexpected result that could have implications for the nation’s rising rates of obesity and associated disease.

A novel drug is being touted as a major step forward in the battle against Australia’s escalating rates of obesity and associated metabolic diseases.

Two in three adults in Australia are overweight or obese. A long-term study between researchers at the Centenary Institute and UNSW Sydney has led to the creation of a drug which targets an enzyme linked to insulin resistance – a key contributor of metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes.

The project has been a collaboration between the Centenary Institute’s Associate Professor Anthony Don, UNSW’s Metabolic research group and its leader Associate Professor Nigel Turner, and UNSW Professor Jonathan Morris’ synthetic chemistry group. Together, they set out to create a drug that targeted enzymes within the Ceramide Synthase family, which produce lipid molecules believed to promote insulin resistance in skeletal muscle, as well as liver and fat tissue.

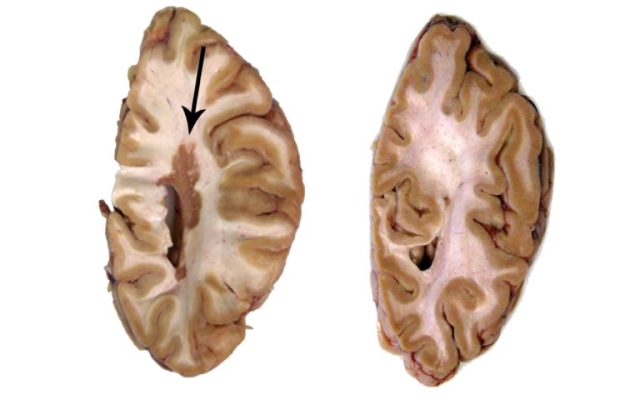

The study has been published in the highly-regarded scientific journal Nature Communications. Surprisingly, although the drug was very effective at reducing the lipids of interest in skeletal muscle, it did not prevent mice (which had been fed a high-fat diet to induce metabolic disease) from developing insulin resistance. Instead, it prevented the mice from depositing and storing fat by increasing their ability to burn fat in skeletal muscle.

“We anticipated that targeting this enzyme would have insulin-sensitising, rather than anti-obesity, effects. However, since obesity is a strong risk factor for many different diseases including cardiovascular disease and cancer, any new therapy in this space could have widespread benefits,” says UNSW Associate Professor Nigel Turner.

While the study produced some unexpected results, it’s the first time scientists have been able to develop a drug that successfully targets a specific Ceramide Synthase enzyme in metabolic disease, making it a significant advancement in the understanding and prevention of a range of chronic health conditions.

“From here, I would like to develop drugs which target both the Ceramide Synthase 1 and 6 enzymes together, and see whether it produces a much stronger anti-obesity and insulin sensitising response. Although these drugs need more work before they are suitable for use in the clinic, our work so far has been a very important step in that direction,” says Centenary Institute’s Associate Professor Anthony Don.

https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/health/surprise-result-researchers-targeting-high-rates-obesity