By David Ho and Cornelia Zou

HONG KONG – As drug developers are racing to find a cure for the new coronavirus, researchers in Hong Kong claim to have made major headway in the development of a vaccine for the virus that has so far killed 132.

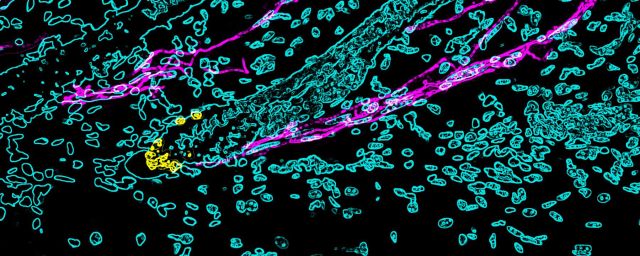

Yuen Kwok-yung, the chair of infectious diseases at the University of Hong Kong’s (HKU) department of microbiology, said in a press briefing at Hong Kong’s Queen Mary Hospital that his team had successfully isolated the novel virus from the first imported case in Hong Kong.

But he said the vaccine still needs months to be tested on animals and an additional year for human trials before it is fit for use.

The vaccine is based on a nasal spray influence vaccine invented by Yuen, a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) expert, and his team.

The race to find a cure is on.

“It will normally take 15 to 18 months to go from obtaining the DNA of a virus to getting an IND for neutralizing antibodies,” Chris Chen, CEO of Wuxi Biologics Cayman Inc. (HK: 2269), told BioWorld. “Because of the possibilities of unexpected mutations, we cannot afford to follow the normal procedures, so we decided to compress the process to four or five months, while complying to all the international standards.”

The company said on Jan. 29 that it has stepped up its efforts in enabling the development of multiple neutralizing antibodies for the novel coronavirus.

Having respectively completed all preclinical CMC for the world’s first yellow fever antibody and the worlds’ first Zika virus antibody in a record timeline of seven and nine months previously, the company is aiming at a five-month mark for the development of new antibodies for the 2019 coronavirus.

“We obtained the virus DNA this week, we will produce the first batch of sample antibodies in the next few weeks, then we’ll ask authorized institutes to test the efficacy of our antibodies before communicating with the National Medical Products Administration and the Chinese Academy of Inspection and Quarantine regarding moving the antibodies forward into clinical study,” said Chen. “And in March, hopefully we’ll be able to start the mass production for human use.”

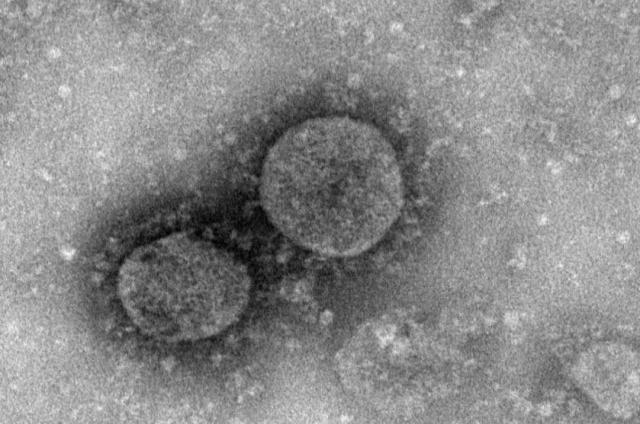

HKU’s Yuen told media that the coronavirus in SARS and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) are in the same family of virus as the new strain.

Consequently, previous drugs used to battle those indications, such as the protease inhibitor Kaletra [lopinavir/ritonavir for HIV-1] and interferon beta, may be tested to see if they are effective treatments.

He added that they would investigate whether the antiviral ribavirin may also be added to those two candidates to improve them.

“We hope we can tell everyone if the drugs are effective in the laboratory after several weeks,” he said.

Yuen recently warned that the virus is entering its third wave of transmission, which would be human-to-human.

The first wave of transmission is believed to be from animal-to-human while the second wave spread from a seafood market in Wuhan to neighboring areas.

“Unlike the 2003 SARS outbreak, the improved surveillance network and laboratory capability of China was able to recognize this outbreak within a few weeks and announced the virus genome sequences that would allow the development of rapid diagnostic tests and efficient epidemiological control,” wrote Yuen and team in a recently published article in The Lancet.

“Our study showed that person-to-person transmission in family homes or hospitals, and intercity spread of this novel coronavirus are possible, and therefore vigilant control measures are warranted at this early stage of the epidemic.”

Global development work underway

Yuen’s HKU team is not the only one in the rush to develop a coronavirus vaccine.

The University of Queensland (UQ) in Australia is also aiming to develop one at an unprecedented speed.

“The team hopes to develop a vaccine over the next six months, which may be used to help contain this outbreak,” said Paul Young, the head of UQ’s school of chemistry and molecular biosciences, in a statement.

“The vaccine would be distributed to first responders, helping to contain the virus from spreading around the world.”

The speedy development is credited to a novel ‘molecular clamp’ technology invented by UQ researchers.

“The University of Queensland’s molecular clamp technology provides stability to the viral protein that is the primary target for our immune defense,” said Keith Chappell, a senior research fellow at UQ’s school of chemistry and molecular biosciences, in a statement.

“The technology has been designed as a platform approach to generate vaccines against a range of human and animal viruses and has shown promising results in the laboratory targeting viruses such as influenza, Ebola, Nipah and MERS coronavirus.”

Oslo, Norway based-public private coalition The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) is supporting UQ’s development efforts. It is also working with biotech firms like Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Moderna, Inc. on vaccines.

Rockville, Maryland-based Novavax Inc. is also working on one.

Others like Salt Lake City-based Co-Diagnostics Inc. claims to have finished the principle design work for a diagnostic.

Some expect that the health care system in China will bear the economic brunt of the virus.

“There is a risk that China’s health care system will not have sufficient resources to control the outbreak, which would mean that economic disruption could spiral further. Health care costs will also increase,” Imogen Page-Jarrett, a research analyst for the Access China division of the Economist Intelligence Unit, told BioWorld.

“The government added drugs used to treat the virus to the drug reimbursement list on January 21st, although patients will still face some out-of-pocket costs. Consumers may be forced to cut their spending, especially on non-essential items, in order to afford treatment or to save money as part of contingency planning,” she added.

Despite the dire situation, there is a silver lining for the pharmaceutical industry: “More positively, pharmaceutical companies will see strengthened demand for vaccines and antibiotics,” said Page-Jarrett.