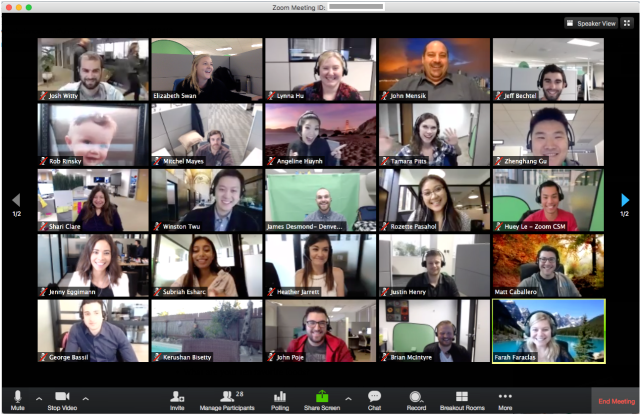

The unprecedented explosion of video calling in response to the pandemic has launched an unofficial social experiment.

BY JULIA SKLAR

JODI EICHLER-LEVINE FINISHED teaching a class over Zoom on April 15, and she immediately fell asleep in the guest bedroom doubling as her office. The religion studies professor at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania says that while teaching is always exhausting, she has never “conked out” like that before.

Until recently, Eichler-Levine was leading live classes full of people whose emotions she could easily gauge, even as they navigated difficult topics—such as slavery and the Holocaust—that demand a high level of conversational nuance and empathy. Now, like countless people around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has thrust her life into a virtual space. In addition to teaching remotely, she’s been attending a weekly department happy hour, an arts-and-crafts night with friends, and a Passover seder—all over the videoconferencing app Zoom. The experience is taking a toll.

“It’s almost like you’re emoting more because you’re just a little box on a screen,” Eichler-Levine says. “I’m just so tired.”

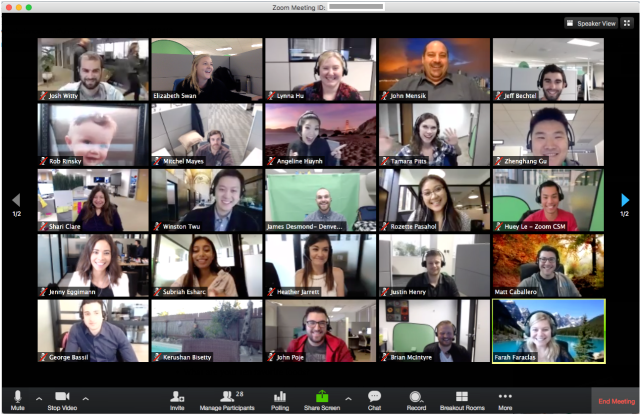

So many people are reporting similar experiences that it’s earned its own slang term, Zoom fatigue, though this exhaustion also applies if you’re using Google Hangouts, Skype, FaceTime, or any other video-calling interface. The unprecedented explosion of their use in response to the pandemic has launched an unofficial social experiment, showing at a population scale what’s always been true: virtual interactions can be extremely hard on the brain.

“There’s a lot of research that shows we actually really struggle with this,” says Andrew Franklin, an assistant professor of cyberpsychology at Virginia’s Norfolk State University. He thinks people may be surprised at how difficult they’re finding video calls given that the medium seems neatly confined to a small screen and presents few obvious distractions.

Zoom gloom

Humans communicate even when they’re quiet. During an in-person conversation, the brain focuses partly on the words being spoken, but it also derives additional meaning from dozens of non-verbal cues, such as whether someone is facing you or slightly turned away, if they’re fidgeting while you talk, or if they inhale quickly in preparation to interrupt.

These cues help paint a holistic picture of what is being conveyed and what’s expected in response from the listener. Since humans evolved as social animals, perceiving these cues comes naturally to most of us, takes little conscious effort to parse, and can lay the groundwork for emotional intimacy.

However, a typical video call impairs these ingrained abilities, and requires sustained and intense attention to words instead. If a person is framed only from the shoulders up, the possibility of viewing hand gestures or other body language is eliminated. If the video quality is poor, any hope of gleaning something from minute facial expressions is dashed.

“For somebody who’s really dependent on those non-verbal cues, it can be a big drain not to have them,” Franklin says. Prolonged eye contact has become the strongest facial cue readily available, and it can feel threatening or overly intimate if held too long.

Multi-person screens magnify this exhausting problem. Gallery view—where all meeting participants appear Brady Bunch-style—challenges the brain’s central vision, forcing it to decode so many people at once that no one comes through meaningfully, not even the speaker.

“We’re engaged in numerous activities, but never fully devoting ourselves to focus on anything in particular,” says Franklin. Psychologists call this continuous partial attention, and it applies as much to virtual environments as it does to real ones. Think of how hard it would be to cook and read at the same time. That’s the kind of multi-tasking your brain is trying, and often failing, to navigate in a group video chat.

This leads to problems in which group video chats become less collaborative and more like siloed panels, in which only two people at a time talk while the rest listen. Because each participant is using one audio stream and is aware of all the other voices, parallel conversations are impossible. If you view a single speaker at a time, you can’t recognize how non-active participants are behaving—something you would normally pick up with peripheral vision.

For some people, the prolonged split in attention creates a perplexing sense of being drained while having accomplished nothing. The brain becomes overwhelmed by unfamiliar excess stimuli while being hyper-focused on searching for non-verbal cues that it can’t find.

That’s why a traditional phone call may be less taxing on the brain, Franklin says, because it delivers on a small promise: to convey only a voice.

Zoom boon

By contrast, the sudden shift to video calls has been a boon for people who have neurological difficulty with in-person exchanges, such as those with autism who can become overwhelmed by multiple people talking.

John Upton, an editor at the New Jersey-based news outlet Climate Central, recently found out he is autistic. Late last year, he was struggling with the mental load of attending packed conferences, engaging during in-person meetings, and navigating the small-talk that’s common in work places. He says these experiences caused “an ambiguous tension, a form of anxiety.”

As a result, he suffered a bout of autistic burnout and struggled to process complicated information—which he says is normally his strength—leading to feelings of helplessness and futility. To combat the issue, he began transitioning to working mostly from home and stacking all in-person meetings on Thursdays, to get them out of the way.

Now that the pandemic has pushed his coworkers to be remote as well, he has observed their video calls lead to fewer people talking and less filler conversation at the beginning and end of each meeting. Upton says his sense of tension and anxiety has been reduced to the point of being negligible.

This outcome is supported by research, says the University of Québec Outaouais’s Claude Normand, who studies how people with developmental and intellectual disabilities socialize online. People with autism tend to have difficulty understanding when it’s their turn to speak in live conversations, she notes. That’s why the frequent lag between speakers on video calls may actually help some autistic people. “When you’re Zooming online, it’s clear whose turn it is to talk,” Normand says.

However, other people on the autism spectrum may still struggle with video chatting, as it can exacerbate sensory triggers such as loud noise and bright lights, she adds.

On the whole, video chatting has allowed human connections to flourish in ways that would have been impossible just a few years ago. These tools enable us to maintain long-distance relationships, connect workrooms remotely, and even now, in spite of the mental exhaustion they can generate, foster some sense of togetherness during a pandemic.

It’s even possible Zoom fatigue will abate once people learn to navigate the mental tangle video chatting can cause. If you’re feeling self-conscious or overstimulated, Normand recommends you turn off your camera. Save your energy for when you absolutely want to perceive the few non-verbal cues that do come through, such as during the taxing chats with people you don’t know very well, or for when you want the warm fuzzies you get from seeing someone you love. Or if it’s a work meeting that can be done by phone, try walking at the same time.

“Walking meetings are known to improve creativity, and probably reduce stress as well,” Normand says.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/04/coronavirus-zoom-fatigue-is-taxing-the-brain-here-is-why-that-happens/