By Jennifer Frazer

In addition to irritatingly lodging themselves everywhere from shower grout to the Russian space station Mir, fungi that live inside rocks in Antarctica have managed to survive a year and half in low-Earth orbit under punishing Mars-like conditions, scientists recently reported in the journal Astrobiology. A few of them even managed to cap their year in Mars-like space by reproducing.

Why were they subjected to such an ordeal? Scientists have concluded over the past decade that Mars (which like Earth is about four and a half billion years old) supported water for long periods during its first billion years, and they wonder if life that may have evolved during that time may remain on the planet in fossilized or even fresh condition. The climate back then was more temperate than today, featuring a thicker atmosphere and a more forgiving and moist climate.

But how do you search for that life? Using life that exists in what they believe is this planet’s closest analogue, a team of scientists from Europe and the United States hoped to identify the kind of biosignatures that might prove useful in such a search, while also seeing if the Earthly life forms might be capable of withstanding current Mars-like conditions.

Which is to say, not nice.

The temperature on Mars fluctuates wildly on a daily basis. The Mars Science Laboratory rover has measured daily swings of up to 80°C (that’s 144°F), veering from -70°C(-94°F) at night to 10°C(50°F) at Martian high noon. If you can survive that, you also have to get past the super-intense ultraviolet radiation, an atmosphere of 95% carbon dioxide (the effect of which on humans was vividly illustrated at the end of Total Recall), a pressure of 600 to 900 Pascals (Earth: 101,325 Pascals), and cosmic radiation at a dose of about .2mGy/day (Earth: .001 mGy/day). I don’t know about you, but Mars is not my first vacation choice.

And it’s probably not Cryomyces antarcticus’s either, in spite of the extreme place it calls home. Cryomyces antarcticus and its relative Cryomyces minteri – the two fungi tested independently in this study — are members of a group called black fungi or black yeast for their heavily pigmented hulls that allow them to withstand a wide variety environmental stresses. Members of the group somewhat notoriously turned up a few years ago in a study that found two species of the group commonly live inside dishwashers in people’s homes (they were opportunistic human pathogns, but most humans are immune to them). But most of these fungi live quietly in the most extreme environments on earth.

The particular black fungi used in this experiment, generally considered the toughest on the planet, live in tiny tunnels of their own creation inside Antarctic rocks. This is apparently the only place they can grow without being annihilated by the crushing climate and blistering ultraviolet radiation of Antarctica. Antarctica also happens to be the place on Earth most similar – although still not particularly similar, as you have seen — to our friendly neighborhood Red Planet. This endurance has made both black fungi and their neighbors the lichens popular test pilots for Mars-like conditions on the international space station.

For example, lichen-forming fungi that create the common and beautiful orange Xanthoria elegans and also Acarospora made the same trip to the ISS previously, in a European module of the International Space Station called EXPOSE-E. Both survived the experience, and Acarospora even managed to reproduce.

But this seems to be the first time a non-lichen forming fungus has received the ISS treatment.

These particular two fungi – Cryomyces antarcticus and Cryomyces minteri – were collected from the McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica in Southern Victoria Land, supposedly the most Mars-like place on Earth. They were isolated from dry sandstone onto a plate of fungus food called malt extract agar. This gelatinous disc was then dried along with the fungus living on it inside a dessicator, and sent into space like that.

Each colony was about 1mm in diameter, and each yeast cell in it was 10 micrometers in size. Like most black yeast/fungi, they have a dark outer wall.

The scientists also tested an entire community of “cryptoendolithic” organisms – those that live secretly inside rocks, including not just fungi but also rock-dwelling blue-green algae – by testing whole fragments of rocks collected on Battleship Promontory in Southern Victoria Land, Antarctica. The various organisms live in bands of varying color and depth within 1 centimeter of the rock surface.

The fungi were launched into space in February 2008 and returned to Earth on September 12, 2009. During that time they were placed in a bath of gasses as similar as possible to the atmosphere of Mars and exposed to simulated full Martian UV radiation, one-thousandth Martian UV, or kept in the dark. They also endured the cosmic background radiation of space and temperature swings between -21.7°C and 42.9°C – much warmer than Mars, but the best that could be done. Control samples remained in the dark on Earth.

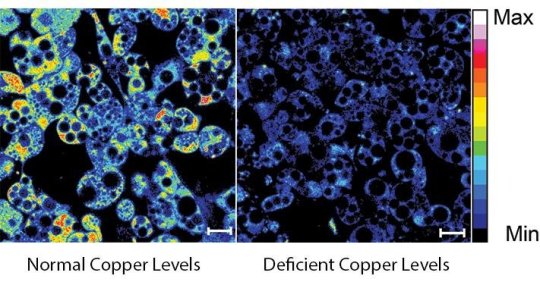

Once back on Earth, the colonies and rock samples were rehydrated. Their appearance had not changed during their voyage. They were then tested for viability by diluting them in water and plating the resulting solution to see how many new colonies formed. They also estimated the percentage of cells with undamaged cell membranes by using a chemical that can only penetrate damaged cell membranes.

The scientists found that the black yeast’s ability to form new colonies was severely impaired by its time on “Mars”, but it was not zero. When kept in the dark on the ISS, about 1.5% of C. antarcticus was able to form colonies post-exposure, while only .08% of C. minteri could. Surprisingly, those exposed to .1% of Mars UV did better, with 4-5 times more surviving: just over 8% for C. antarcticus and 2% for C. minteri. Perhaps the weak radiation stimulated mutations or stress-response proteins that might have helped the fungi somehow.

With the full force of Martian radiation, the survival rates were about the same as for those samples kept in the dark, which is to say, nearly nil. By comparison, about 46% of control C. antarcticus samples kept in the dark back on Earth yielded colony forming units, while only about 17% of C. minteri did. Not super high rates, but still much higher than their space-faring comrades.

On the other hand, the percentage of cells with intact cell membranes was apparently much higher than the number that could reproduce. 65% of C. antarcticus cells remained intact regardless of UV exposure, while C. minteri’s survival rates fluctuated between 18 and 50%, again doing better with UV exposure than in the dark. Colonized rock communities yielded the highest percentage of intact cells of any samples when kept in the dark – around 75%, but some of the lowest when exposed to solar UV, with just 10-18 % surviving intact.

What explains this apparent survival discrepancy between being alive and being able to reproduce? It may be that the reproductive apparati of the fungi are more sensitive to cosmic radiation than their cell membranes and walls, the authors suggest.

The authors’ results also suggest to them that DNA is the biomolecule of choice to use to search for life on Mars, as it, like the cell membranes, survived largely intact even in cells that could no longer reproduce.

Although Mars-based life may not use DNA genetic material, then again, it just might. It certainly seems to have worked well for us here on Earth.

Even though few of the fungi exposed to Mars-like conditions survived well enough to reproduce, in all cases, at least a fraction did. Perhaps that is the material thing. A similar previous experiment showed one green alga, Stichococcus, and one fungus, Acarospora were able to reproduce after a very similar trip on the space station. Another experiment with the bacterium Bacillus subtilis found that up to 20% of their spores were able to germinate and grow after Mars-like exposure. Theoretically, it only takes one or two to hang on and adapt to these conditions to found a whole lineage of Mars-tolerant life (the major reason, by the way, for NASA’s Planetary Protection Program).

On the other hand, some have suggested that long-term survival of Earthly life is impossible on Mars. Given the extremely low reproductive ability after just 1.5 years, this study did nothing to undermine that idea either.

But all of our studies have tested life that evolved on Earth. What about life that evolved on Mars? There’s just no telling how similar or dissimilar such creatures — supposing they exist or ever existed – might be.

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/artful-amoeba/fungi-in-space/